Mysteries of the Maya

The Maya didn't leave behind much, but their legacy in astronomy and their ruins have researchers very interested.

Imagine yourself the chief astronomer-priest of an ancient jungle empire. From your studies of records kept by astronomers for centuries before you, you are convinced that an eclipse of the Sun is likely to occur in three days' time. It is essential for you to inform the people of the empire of this event, so they will be prepared if the Sun begins to disappear.

Quickly, you call a meeting of other priests in the green, grassy square where your people gather for religious ceremonies. The square is surrounded by huge stone pyramids, each carefully placed and elaborately carved, and beyond them lies the jungle. You explain to the priests what must be done. Instantly, each of them dispatches a messenger to a far corner of the empire, to warn the people of the coming eclipse.

Can the messengers travel that far through the dense jungle in only three days? You have no fears upon this point, for you know that the messengers are traveling by canoe over an intricate network of canals connecting all parts of the empire. You are sure they will reach their destinations in time. They must.

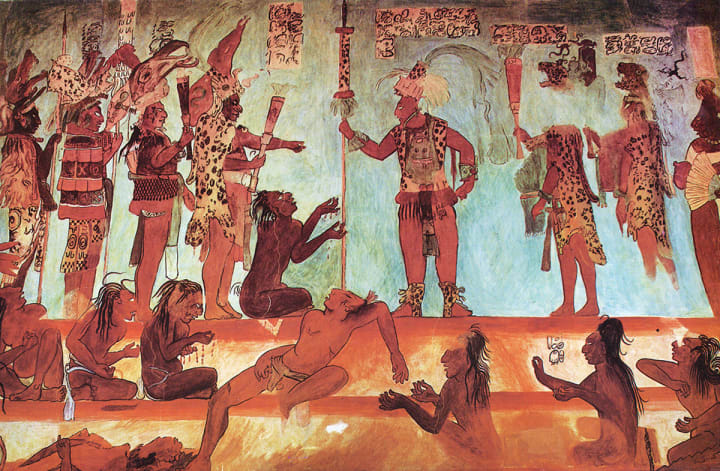

Photo via Mexican Archeology

The Moment of Truth

On the day of the predicted eclipse, people from miles around gather in the square. You and the other astronomer-priests put on ceremonial headdresses made of hundreds of brightly-colored feathers. Together, you mount the steps of the largest stone pyramid and lead the people in a religious chant. You beg the gods who rule this day and month to protect the Sun from danger during the eclipse, or to prevent the eclipse from happening at all.

Suddenly, you notice that a corner of the Sun has disappeared! It is as if a huge celestial monster were eating the Sun! Gradually, the dark area of the Sun grows. You recall reading in the record books of rare occasions when the entire Sun's disk was blotted out and darkness fell upon the land at midday. But that does not happen this time. You are glad to see the bright portion of the Sun growing again.

After a while, the Sun has returned to its normal, round shape. You lead the people in a chant of thanks to the gods, then dismiss them so they may return to their homes and farms. You resolve to record this event in the record books yourself, so future astronomer-priests will know of it.

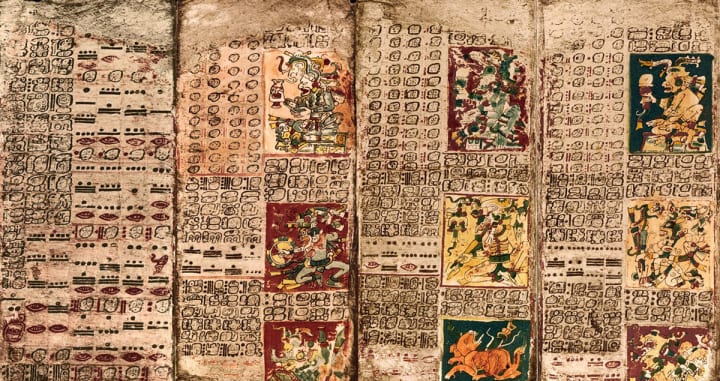

Photo via Cycles of Change

Meet the Mayans

Something like this may have occurred in the jungle lowlands of Mexico between 300 and 1000 A.D. During that time, a group of people called the Maya had a highly developed civilization in the area. They built ceremonial centers with huge stone buildings that were used for religious purposes. They constructed an elaborate system of canals through the jungle. Perhaps most importantly, they kept track of movements of celestial bodies such as the Sun, the Moon, the planet Venus, and certain stars. They developed a complex calendar around these objects, and they may even have been able to predict eclipses of the Sun and Moon.

How do we know so much about a long-vanished group of people? The Maya civilization had decayed and all but disappeared by the time Spanish explorers and conquerors arrived in the early 1500s. The ceremonial centers and the canal system had been overgrown by a thick tangle of jungle plants. Few of the surviving Maya understood the astronomical knowledge collected by their ancestors and passed down through the generations. Saddest of all, the Maya record books were heaped into a pile and burned by the Spanish. Almost all the evidence of a civilization that had existed for hundreds of years had apparently been wiped off the face of the Earth.

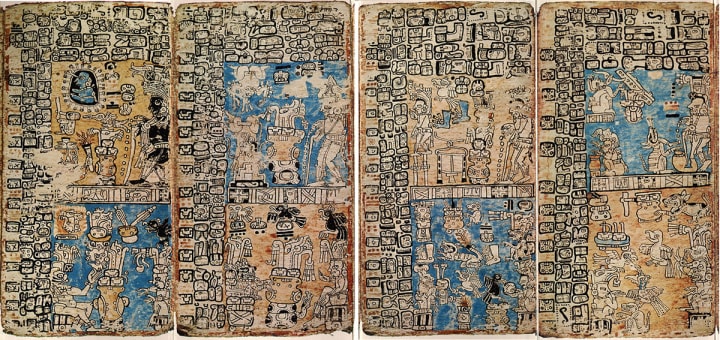

Photo via Message to Eagle

A Few Clues

Not quite all the evidence disappeared, however. During the last century or so, some of the Maya ceremonial centers have been discovered and freed from their tangle of overgrowth. A few Maya "books" have been found as well, miraculously preserved over the ages.

Some scientists have tried combining the techniques of archeology with a modern knowledge of astronomy to interpret these artifacts. The scientists, called archeoastronomers, have given us a better understanding of the Maya and have helped us realize that these people must have had a long-lived and stable civilization to make the observations they did.

For instance, take some of the observations recorded in the few surviving Maya "books," or codices. Codices are not really books; They are long strips of Mesoamerican bark cloth with Maya hieroglyphic script which have been folded back and forth like a fan to make pages. Spanish conquerors burned practically all of the codices in the early 1500s, but they evidently kept a few as souvenirs or curiosities. These codices wound up in libraries of Europe, where they were forgotten for hundreds of years. In our time, archeologists have discovered three or four of them and have spent much time trying to interpret them. In particular, a codex (singular of codices) found in the city of Dresden, Germany, seemed to contain astronomical observations.

On three pages of the Dresden codex, there is a series of numbers written in the unusual base 20 system of the Maya. Most of the numbers are 177s with an occasional 148 thrown in. There is another series of numbers which keeps a running total of the 177s and 148s.

Photo via Maya Codices

Early Eclipse Table

Astronomers studying the Dresden codex realized that 177 is the number of days between six full moons and 148 is the number of days between five full moons. Why would anyone want to keep track of intervals of five or six full moons? The answer may be that lunar eclipses are likely to occur at these intervals.

For instance, take the two partial lunar eclipses that happened in 1981, one on the night of January 19-20 and one on the night of July 16-17. These two eclipses were six full moons, or 177 days, apart. Occasionally, when the orbits of the Earth and Moon are just right, eclipses will occur after only five months instead of six. Thus, if you kept count of 177 day intervals, with a 148-day interval thrown in every seven or eight times, you could make an educated guess as to when lunar eclipses might occur. Of course, some of them would happen when your side of the Earth was facing away from the Moon, so you would miss them. Many of the eclipses would be partial, and you might not notice them unless you looked very carefully. Still, you would have some way of predicting which full moons might be eclipsed.

The same system could be applied to eclipses of the Sun, if the 177- and 148-day intervals were measured between new moons instead of full moons. However, although there may be two or three eclipses of the Sun a year, each one is visible from only a small portion of the Earth. The Maya would have had to observe these eclipses for many years to detect a pattern to them. Eclipses of the Moon can be seen from half the Earth at a time; Therefore Maya astronomers would have seen more of them. Modern archeoastronomers argue that the eclipse table in the Dresden codex was probably a lunar eclipse table because it extended over only 33 years, too short a time for a solar eclipse table.

Was this table merely a record of eclipses the Maya observed, or was it a means of predicting future eclipses? No one today is sure, but some archeoastronomers believe that if the Maya could detect eclipse patterns, they could, without too much trouble, make educated guesses about future eclipses. In fact, they may have been better at predicting eclipses than astronomers living in Europe at the same time.

Photo via Chaa Creek

Architects of Astronomy

In addition to the codices, the Maya left other artifacts which indicated their interest in astronomy. For instance, some of their buildings appear to be oriented toward directions where important astronomical objects rise and set. Archeoastronomers have measured the orientations of many Maya buildings in a search for ones specially built to an astronomical plan.

The most famous of these buildings is the Caracol in a ceremonial center called Chichen Itza. This round, stone building contains a staircase which spirals upward like the shell of a snail (caracol in Spanish). At the top of the building, three windows look out across the treetops, one pointing toward the south and the other two aiming at the northernmost and southernmost places where Venus may set. The Caracol may thus have been an observatory where records of Venus' motion were made.

In another ceremonial center called Uxmal, there is an impressive building which the Spanish named the Governor's Palace, although the Maya probably didn't use it for that purpose. If you stand on the front steps of the building, you can look out over a stone pillar and an altar in the shape of a two-headed jaguar toward another ceremonial center called Nohpat, miles away. You are also looking at the southernmost place Venus can rise. The Governor's Palace may have been purposely built to point in that direction.

Photo via Travel Channel

Just a Coincidence?

Or was it? Could the alignments of both the Governor's Palace and the Caracol have been accidental? There are several tests we may apply to help us answer these questions.

First, are these buildings lined up with other buildings, or is there some logical reason for them to point in these directions, other than an astronomical one? In both cases, the answer is no. The Governor's Palace is skewed out of line with the buildings around it, for no apparent reason. A floor plan of the Caracol shows that it is a very oddly-shaped building with no perfectly square corners in it. The Venus orientations are the most logical reasons anyone can find for the shapes of these buildings.

But was Venus an important object to the Maya? Should they have bothered to orient buildings toward it? In this case, the answer is yes. The Maya regarded Venus as one of their most important gods, a king called Quetzalcoatl. Not only does Venus appear often in Maya legend, but a table of its motions also appears in the Dresden codex. There is plenty of evidence that the Maya were interested in Venus.

None of these arguments proves that Maya buildings were definitely oriented toward Venus. They merely show that it is very likely they were. Short of bringing back a live Maya astronomer from the 10th century, there is no way we can have proof of any of these ideas.

There is still much more to be learned about the Maya and their astronomy. Parts of the existing codices have never been understood, and it is possible other codices may be discovered in the future to furnish us with more information. It is very likely that there are many Maya ceremonial centers in the jungles of Mexico and nearby countries that have not yet been discovered. Who knows what can be uncovered.

Recommended Reading

Many scientists have dedicated their work to solving the mysteries of the Maya. Learn more about the discovery of the Maya civilization, their astronomical studies, and their culture in Jungle of Stone.

Jungle of Stone explores the discovery of Maya civilization by western scientists, including the journeys of John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood. Carlsen's tale is based on his own research and a 2,500 mile journey through the Yucatan and Central America, correcting our understanding of Stephens' and Catherwood's work, and of the Maya themselves.

About the Creator

Futurism Staff

A team of space cadets making the most out of their time trapped on Earth. Help.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.