History of Science Fiction Part III

In the third part of the History of Science Fiction, we look at the second half of the 20th century, from 'Doctor Who' to 'Dune,' from 'Star Trek' to 'Star Wars' –and beyond.

At the dawn of the 1960s, the history of science fiction took a huge turn from its past. In two decades, the whole genre of sci-fi would change in ways that would alter mainstream perspectives of the science fiction genre.

From a world covered in sand and worms to a singular explorer viewing time and space from a little, blue box. From a starship exploring the final frontier to a farm boy with a laser sword. And in the years that followed, science fiction would go even further beyond.

50 years altered the history of science fiction forever.

Before television hosted the exploits of the final frontier, a single television writer would forever alter the public's perspective of science fiction.

While Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke had been hard at work crafting literary works of science fiction, mainstream audiences knew only of the monster and alien focused science fiction plots in B-movies.

Enter Rod Serling and his little show: The Twilight Zone.

The Twilight Zone is the first great anthology science fiction series to air on television. Shows like The Outer Limits would follow. Every episode told an stand-alone story dealing with a simple moral. It bared much resemblance to another popular show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Both were genre shows dealing with a new mystery or scenario every episode. Both shows centered around a creative personality.

While Sterling was no Alfred Hitchcock, he did manage to bring a unique style to The Twilight Zone. Scientific explanation was never more important than an episode's story and characters.

In one episode, the Earth draws closer and closer to the sun. Why? Doesn't matter. The human reaction to such an event was far more important to the story.

A camera takes photographs that foretell the future. Why? Who cares? It's more interesting to know how people would react to such an event.

Rod Serling brought a literary intelligence to science fiction, using schlocky tropes and concepts in order to relay important morality tales, all with popular character actors appearing along the way.

While most people know that Rod Serling was the main mind behind The Twilight Zone, many forget his other contributions to the history of science fiction.

An obscure French novel named La Planète des Singes by Pierre Boulle was optioned by Fox Studios. Many writers wrote scripts for the proposed film. Rod Serling handed his attempt to the studio. While the script was immediately rejected, it was revised later by writer Michael Wilson, with numerous elements, including a brilliant twist ending, retained from Sterling's original script.

La Planète des Singes became Planet of the Apes.

Serling died at the age of 50 from a heart attack. Considering how many great works science fiction writers have crafted in their advancing years, one imagines how many great works we lost thanks to Serling dying young. After all, by 1968, he had already revolutionized the history of science fiction twice.

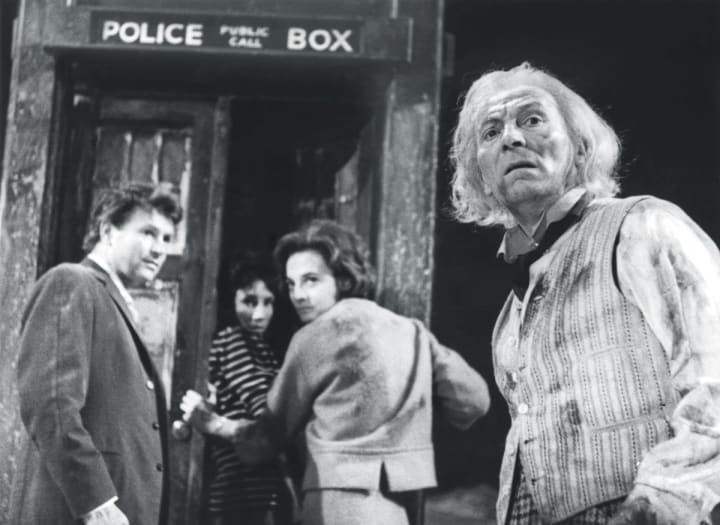

Doctor Who

Doctor Who

The 1960s were a great era for science fiction television. While Rod Serling brought The Twilight Zone to American TV, the BBC attempted to create an educational family program for British audiences.

The intention was to create a program that would bring children to every period of classical history, guided by an enigmatic old man in a blue box – a blue box that was bigger on the inside.

In doing so, the BBC forever altered the history of science fiction.

Doctor Who aired in 1963, and, for over 50 years, proved a staple of science fiction broadcasting. While at first merely educational television, it transcended its limits by traveling deep into the future, encountering countless crazy and memorable science fiction alien races.

The two most memorable – and unique – were the Daleks and Cybermen. Both introduced new concepts for viewers unlike anything they had ever seen before. While we can laugh right now at trashcans with whisks and plungers for weapons, everything about Daleks from their design to voice to their very existence proved unlike anything before seen on television.

But the key to the show's long-running success proved to be the Doctor himself. An alien intellectual who, upon dying, could transform into a new form – allowing the character to survive from year to year. Whenever one actor grew tired of the role, they could retire, and a new actor could replace them. Regeneration. And each version of the Doctor had a slightly different personality, allowing the character to remain fresh in the eyes of the audience.

The show did dip in popularity toward the end of the 80s. However, after an almost 20-year hiatus, the show returned in 2005, and has enjoyed immense population afterward.

Many often regard Doctor Who as one of the Big Three Sci-Fi properties, much like how Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke are regarded as the Big Three Writers of Sci-Fi. The other two works that hold as important a position in the history of science fiction as Doctor Who? Star Trek and Star Wars.

Science Fiction Literature

Frank Herbert's Dune

The 60s proved a revolutionary era in the history of science fiction. Many of the most important science fiction novels were published in that decade. Many of the works focused on breaking apart societal standards and rejecting the status quo. In many respects, this reflects the cultural mindset of the time, given the rising popularity of the women's liberation and civil rights movements.

Ursula K. Le Guin published many classic speculative fiction toward the end of the 60s. Aside from A Wizard of Earthsea, which changed the history of fantasy fiction for years, Le Guin published a novel called The Left Hand of Darkness, which confronted readers with a strange world where aliens were neither male or female, forcing audiences to confront the stifling conformity of gender roles.

Robert Heinlein, one of the Big Three sci-fi writers of the 50s and 60s, published Stranger in a Strange Land, a science fiction novel that presented a young Martian colonist coming to Earth for the first time in his life, and being unable to comprehend the staggering new culture he found himself living in.

However, of all science fiction published in the 60s, one stands above all others as a cultural landmark – as one of the most important works of fiction in the entire genre of science fiction: Dune.

Frank Herbert's Dune created a whole universe in space. In the distant future, mankind has become dependent of the geriatric spice Melange.

The spice, thanks to its power to fold space, has become invaluable. Without spice, travel between worlds light-years apart would be impossible, and the new empire would fail. Additionally, many people became addicted to spice as a drug - and withdrawal is fatal.

Melange only exists on one planet: Arrakis. Dune. Desert planet.

But the story, rather than focus on hard science, focused instead on the political conflicts between warring houses, racial bigotry between the Empire and the native Fremen who dwell on Arrakis, and the origins of religious fanaticism.

Frank Herbert covered a great deal of ground with his one novel. He combined the sensibilities of J.R.R. Tolkein's Middle-Earth with the world of science fiction.

And, yes, once again, he influenced a young film maker named George Lucas. We'll get to him later.

It is apparent at this point in the history of science fiction that science played less and less of an important role in the narrative. As seen with The Twilight Zone, Doctor Who, and even Dune, writers (and in turn audiences) valued story and characters over adherence to scientific fact. They did not disregard science, but just cared more about the "fiction" part of science fiction.

But it is wrong to discuss the 60s and sci-fi without mentioning one great writer.

Arthur C. Clarke is often regarded as one of the Big Three sci-fi writers, and for very good reason. Clarke started writing science fiction in the late 40s, with a short story known as "The Sentinel." The story centered around astronauts who, upon traveling to the moon, discovered a monolith underground. Who put it there? What was its purpose? A mystery – unexplained.

The story was rejected by the BBC, but Clarke held onto the story, publishing it a few years later, but never forgetting it.

Clarke went on to publish the novel Childhood's End, which, for many years, was regarded as his magnum opus. The story told of aliens who come to Earth, and, rather than invade through violence, gradually take over the planet by enhancing the human experience. While the aliens have an insidious motivation for all this, the ultimate objective of their "invasion" proves at once shocking, disturbing, and transcendent.

While Asimov and other science-heavy science fiction writers focused on the mathematical and concrete, Clarke focused on the abstract, unusual elements of the genre. He proposed that an alien intelligence would prove to us to appear almost magical, due to the insanely advanced technology they would wield.

In the middle of the 1960s, Arthur C. Clarke met with film director Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick wanted to create a science fiction story, and the two decided to collaborate: Clarke writing and Kubrick directing. Clarke remembered his short story "The Sentinel," and decided to expand it to a novel length story.

Clarke wrote the novel and script to what would eventually be known as 2001: A Space Odyssey.

To this day, it is regarded as one of the most brilliant science fiction films ever created. Kubrick's film and Clarke's novel provided a drastically different perspective on the same narrative. While Clarke elected to focus more on the narrative, Kubrick focused more on the audio-visual experience.

Regardless, both the book and film of the same name are among the most important works in the history of science fiction.

But before the 60s had ended, one of the most important works of science fiction would be released, one that would go mostly unacknowledged throughout most of the decade, and only become a cultural landmark in the years following its cancellation.

Gene Roddenberry's primary intention when creating Star Trek was to create a frontier show in space. Westerns proved to be a very popular genre for television, and much of that had to do with the concept of adventure, of going off to the new frontiers of America, just to see what was out there.

At the same time, Roddenberry wished to discuss the social issues of the time – racism, prejudices, Cold War tension – in a non-threatening manner, one that could open minds without confronting them with direct horrors of the time.

And, thus, he created Star Trek.

The series presented an optimistic, hopeful view of the future. Racism and other prejudices had been deemed an outdated mentality. Technology made everyone's lives better. In the worst of times, it offered light.

Despite Roddenberry's efforts to create a non-threatening program, he pushed boundaries. Television censors were stunned when the first interracial kiss aired on television. A landmark occurrence, especially given the cultural situation at that time.

Star Trek was cancelled after three seasons. It only became popular when reruns hit airwaves. It would go on to spawn a series of films, multiple spin-off series taking place at different points of time in the chronology, and, perhaps most important of all, a fanbase.

Star Trek's single greatest contribution to the history of science fiction remains the presence of a massive, loyal fanbase. Before, science fiction did have a fanbase, but never before was there a fanbase this driven and intensely in love with a given property as with Star Trek – except, of course, the comic book fandom (which kind of is its own separate thing with its own separate history).

The Slow Period

Star Trek

Star Trek popularized the concept of going into space and reaching the stars, just as humanity fulfilled JFK's promise of putting a man on the moon.

Yet, oddly enough, the landscape of science fiction dulled in the early-to-mid 70s. While Star Trek's rediscovery inspired more interest in the genre, few science fiction films really appeared at this time.

Planet of the Apes spawned a series of sequels, Invasion of the Body Snatchers was remade (successfully), and a few science fiction art films (such as The Man Who Fell to Earth) hit cinemas.

Writer Phillip K. Dick published the majority of his works in the late 60s and 70s. Dick, in his lifetime, went under-appreciated. He viewed a world of unreality, of distorted perspectives. Many of his stories would later be adapted into beloved science fiction films, such as his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (adapted into Blade Runner), Total Recall, and Minority Report. At the time, however, Dick was dismissed as a loon. Now, he is acknowledged as a genius.

But, for a while, science fiction became cheesy again. A niche market without real room for quality.

Many of the science fiction films of the early 70s dealt with dystopian societies. Arguably the best sci-fi film of this era, A Clockwork Orange, is in many respects a science fiction film, though more social sci-fi like Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. Other sci-fi films like this included Soylent Green, Logan's Run, The Omega Man, and a little film called THX 1138.

For much of the 70s, the director of THX 1138 tried to release a science fiction film. Most of the drafts were rejected. His scripts and proposals for a science fiction epic were revised time and time again.

But, eventually, following the release of Jaws and the new interest in big, summer blockbusters, George Lucas was able to release his magnum opus: Star Wars.

Star Wars is the culmination of all science fiction to come before it. In many ways, it reshaped the entire culture of science fiction. The genre, over night, was redefined. The history of science fiction was never the same following the release of this single film.

There is no need to explain the plot of Star Wars. You know it. Nor is there any need in me explaining its influences. You've already read of them. Everything from the 20s pulps to the works of Asimov and Herbert influenced Lucas across the span of his movies.

Star Wars brought a renewed interest in science fiction – the likes of which had never been seen before. It was in the years that followed Star Wars that Battlestar Galactica first came on the air, that Star Trek's various movies and spin-offs came out. Without Star Wars, you would not have E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. You would not have David Lynch's adaptation of Dune.

Lucas proved with the original Star Wars that special effects could bring anything the imagination conceived of to life. Lucas proved that special effects could be a means to tell any story. This led to countless special effects-driven films to follow.

But Lucas, when creating his prequel trilogy, proved that, for many film-makers (including Lucas himself), the story could also be a means to present good special effects.

Compare, for a moment, Earth vs. The Flying Saucer – a film with Ray Harryhausen's stop-motion special effects – and Independence Day. The two films have the same essential plot – aliens come down, and attack national monuments.

However, due to the time-consuming process it took to bring Harryhausen's effects to life, the effects were used minimally, and a focus was put on the tension of the situation. The effects merely grounded that tension.

On the other hand, Independence Day had the technology to bring any number of awe-inspiring visuals to life, and, thus, each plot point leads to the next set piece. The point of Earth vs. The Flying Saucer is that aliens attack earth. The point of Independence Day is that the White House blows up.

The 80s and Dark Sci-Fi

The Thing (1982)

Following Star Wars, 20th Century Fox took a script sitting for years in development hell, and put it into production. The film focused on space truckers who, after answering a distress call, became the victim to a horrible alien.

While Star Wars changed the way movies were made, Alien changed the science fiction genre as a whole. While Star Wars and Star Trek presented space as a place full of adventure, Alien harkened back to Lovecraftian horror by stating that science may lead to our ultimate destruction.

For the 80s, this was the modus operandi. The history of science fiction is incomplete without talking about the multitude of nightmarish films and books focused on technology's short comings.

John Carpenter's remake of The Thing presented an alien lifeform that replaced human beings. When expose, the copy would transform into a grotesque nightmarish creature.

David Cronenberg released countless films using body horror to directly criticize scientific advancement and the misuse of technology. While many point to his remake of The Fly as his masterpiece, many often neglect Videodrome, his film that discussed the blurring between the world of entertainment and reality.

Many writers took this to the next level. Writers like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling (starting in the pages of OMNI Magazine itself) stirred up the history of science fiction with the creation of cyberpunk – a sci-fi subgenre focused on how technology can make the future awful, where organizations rule with an iron fist.

The history of science fiction would forever be altered by the formation of cyberpunk, which defined the aesthetic of 80s sci-fi: businesses own everything, humanity becomes cybernetic, and everything is dark.

Films like The Terminator and WarGames would take this one step forward by presenting a future where killer robots – once believed to be a science fiction cliche – could indeed eradicate humanity. All it would take is one computer with access to the nuclear launch codes to send the planet to oblivion.

Other works, such as Mad Max, didn't even bother explaining how we would bite the bullet. They just assured us that, in the coming years, we were all going to die.

Even the lighter science fiction, such as RoboCop, proved incredibly cynical about our prospects as a race.

Even Japan joined in on the action. Two of the most important science fiction films of the 80s came straight out of Japan: the animated masterpiece Akira and the surrealist cyberpunk film Tetsuo: The Iron Man. Both featured bizarre body horror, as well as a message of pure nihilism.

It is telling that Phillip K. Dick, ignored for almost all of the 70s, became immediately popular in the dark, cynical landscape of the 80s. For many, the most important 80s science fiction film remains Ridley Scott's sophomore effort in the genre, Blade Runner, adapted from Phillip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Blade Runner directly confronted the questions of humanity. If we create synthetic life, who is to say it is any less than a man? Who is to say that a robot with thoughts, feelings, and emotion is less than human?

90s Hope

The Matrix (1999)

I don't know why the 90s proved a lighter decade in the history of science fiction. Maybe we just felt tired of how dark things had gone. Perhaps we realized that, after a decade of fear, we still hadn't killed ourselves.

However, starting with Terminator 2: Judgement Day, sci-fi became lighter. Consider all of the most important sci-fi films of this era. Jurassic Park questioned whether or not we should play God, but, at the same time, all the good people live in the end, resulting in a fun thrill ride.

Independence Day showed aliens striking down humanity, but, in the end, we'd emerge triumphant. Gattaca presented a future where humanity is judged by our genetic material, yet dreams can still come true even in the face of unimaginable odds.

And Men in Black? Hell, Men in Black said that aliens coming to Earth would be less like Invasion of the Body Snatchers and more like a dull trip through airport customs.

Writers like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, once the fathers of the cyberpunk movement, looked back to the past, to the works of Jules Verne and the scientific romantics, and, combining old and modern sci-fi sensibilities, crafted the genre of steampunk.

Even Japan lightened up. While cynical cyberpunk works still came out (the mostly-forgotten Genocyber remains one of the most misanthropic works of fiction ever), one of the most important sci-fi films of the 90s, Ghost in the Shell, provided a nuanced perspective of an increasingly cybernetic future.

It questioned what it meant to be human, yes, and it showed the horrors of cybernization, but never once did it paint a future of doom and gloom like Akira.

Even truly dark affairs like Starship Troopers presented morbid, dark futures with a hint of fun and a wink.

The hope permeated even through works like The Matrix, which insisted that the world we lived in did not really exist, but was merely a computer program designed to keep humanity enslaved.

A New Millennium

The Martian (2015)

It is hard to categorize the new millennium in the greater history of science fiction. We are too close to the films of yesteryear to properly assess how relevant each film and story will be in the coming years.

Already, films like The Martian, Interstellar, District 9, and Arrival have proven that science fiction has a place in serious art. Star Wars, Star Trek, and countless other properties prove relevant still. While others, like The Terminator, have fallen into irrelevancy.

But it is important not to make too many judgements about every new science fiction film that comes out and its role in history. Upon release, James Cameron's Avatar proved an incredible success. It remains the highest grossing film of all time.

Yet not a single film has drawn from it for inspiration. It is a cinematic landmark, yet it barely left a ripple in the public consciousness.

Consider Gravity, which, upon release, received multitudes of critical acclaim. Many people touted it as one of the best, most clever science fiction films made.

Years later, it is hardly discussed.

Meanwhile, a little film called Moon – made with almost no money, barely noticed on release – has only become more highly regarded with the passing of years. More and more people acknowledge it as a masterpiece, despite the fact that no one saw it when it came out.

If you have learned anything, going over the course of hundreds of years in science fiction history, it is this: this genre you love, with its consistent iconography and imagery, has never been a fixed point. It has never been stable. With every year, the genre grows and changes. It is a living thing – like time itself.

And what we see – the last 40 years since the release of Star Wars – is but a blink in the eye of the genre. The history of science fiction is a long and storied one. And, from the looks of things, it will not find its end any time soon.

About the Creator

Anthony Gramuglia

Obsessive writer fueled by espresso and drive. Into speculative fiction, old books, and long walks. Follow me at twitter.com/AGramuglia

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.