History of Science Fiction Part II

In the second part of the History of Science Fiction, we look at the first half of the 20th century, from the start of the pulps to the rise of literary science fiction.

At the start of the 20th century, the history of science fiction took a great turn thanks to the emergence of motion pictures and the proliferation of pulp magazines. It is thanks to these two entertainment forms that the landscape following H.G. Wells' sci-fi novels took such a different direction than the scientific romances of the 19th century.

With the proliferation of high budget science fiction, the fires of imagination were spurred on for a generation of writers and directors in the coming years. But, tending to the fertile soils of creativity, pulps and science fiction writers created brave, new concepts – from planets comprised entirely of cityscape to alien intelligences too grand for the mind to comprehend. The history of science fiction took a huge turn at the beginning of the 20th century, leading into the end of the 50s with a beautiful future dead ahead.

The first science fiction movie made was A Trip to the Moon, released in 1902. It is hard to imagine that, four years following H.G. Wells' The War of the Worlds, this silent movie came out. So little time passed, really, between these two landmarks in science fiction. It proved to the audiences of the world that the fantasies on the written page could be brought to life on the silver screen.

While A Trip to the Moon may be dull for modern audiences, at the time, it left audiences stunned. It truly was unlike anything they had ever seen. Though expensive, it proved worth the investment.

Many silent sci-fi films sprang up in the early years of cinema. The Mechanical Man (1921) was an early attempt at presenting a killer robot. Thomas Edison's adaptation of Frankenstein (1910) was an early adaptation of the Mary Shelley novel (completely out-shined by Universal's later version).

But the two silent sci-fi films that altered the history of science fiction are The Lost World (1925) and Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927).

The Lost World is the film adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's story of the same name. The film and story follow the same plot, featuring adventurers uncovering an island where dinosaurs roam. This was the first time anyone attempted to create dinosaurs using stop-motion animation. The special effects were done by Willis O'Brien, who would later do the effects in the classic monster movie King Kong (1933).

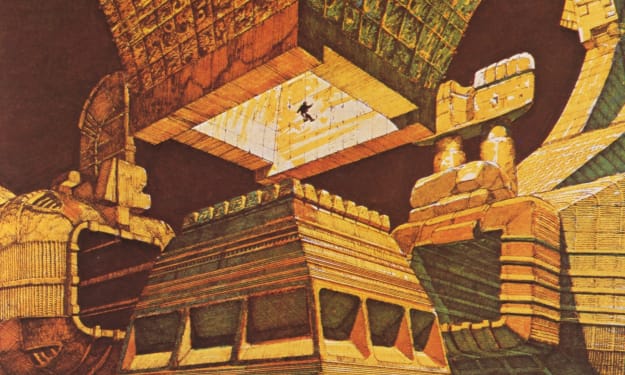

But arguably more important to the science fiction genre is Fritz Lang's Metropolis, which remains arguably one of the most influential science fiction movies of all time. The film depicts a futuristic city where the super rich and working class are divided – an obvious metaphor for Germany's post-WWI economy where, following the Treaty of Versailles, the country had fallen into ruin. Again, like Wells, Lang uses science fiction as a commentary for contemporary social issues. The main character's whole goal, along with his lover Maria, is to bridge the gap between the rich and the poor for the good of the city.

All the while, a robot named Hel is created, who, taking the physical form of Maria, seduces countless men into madness. Insanity ensues.

Aside from just being a really well-told story, Metropolis is significant in the history of science fiction for, again, being the first film of its kind. Several film makers, most notably George Lucas to Ridley Scott, would draw from Metropolis when creating their own science fiction epics.

Unlike A Trip to the Moon and The Lost World, however, Metropolis was not an immediate hit. It would be rediscovered years later. People didn't want social commentary at this point in time. No, people wanted to go into space and see dinosaurs come to life. They had little interest in mega-cities.

And the pulps reflected this.

With the proliferation of newspapers featuring serialized narratives, many publishers tried to create their own magazines made from cheaper quality paper (to keep budgets down). These magazines were referred to as "pulp magazines," since the paper was comprised of the pulpy leftovers from professional paper.

By 1912, countless writers had published adventure stories – mostly Westerns. One young writer, after going through a series of odd jobs over the course of his life, decided to give writing the ol' college try. His attempt at writing resulted in a saga that would reshape the history of science fiction.

The writer's name was Edgar Rice Burroughs, the future creator of Tarzan. And that story was A Princess of Mars, the first entry in what would be referred to as the Barsoom saga, an 11-book series depicting the adventures of a Confederate soldier, John Carter, and his adventures on the planet Mars.

With space becoming more and more interesting to a then-contemporary audiences, more and more people drew inspiration from Burroughs, writing their own stories of heroes on foreign worlds, going on adventures. These stories drew heavily from the scientific romances of Verne's lifetime, and, in turn, became known as "planetary romances."

Again, these were hardly the first stories of this kind. Stories of people traveling to and from other worlds had been around for hundreds of years, ever since the start of science fiction. However, it was here that certain tropes and archetypes started coming about.

Planetary romances featured strong jawed heroes who fought aliens and robots, saved maidens, and explored unchartered territories. Many of these stories, unfortunately, veered into problematic territory. Many of the aliens were thinly veiled racial stereotypes, and many of the women were mere damsels.

To his credit, Burroughs tried to avoid these stereotypes. Many of his good aliens were people of color, and he, when possible, would have his heroines kick butt. Sadly, what was progressive for its day may come across as problematic by today's standards.

Burroughs' writings would later inspire the creation of characters like Buck Rodgers and Flash Gordon, who filled comic books and movie screens for years to come.

And, yes, George Lucas would later draw from these guys, too, when creating Star Wars. Almost everything in this era will inevitably lead back to Star Wars. The history of science fiction really can be divided between what influenced Star Wars and was influenced by Star Wars.

Writers in this time looked to the stars, and saw the potential for adventure.

At least, most did. There was one pulp writer who looked to the stars, and saw the dark, emptiness of space. And, in his own way, he proved just as vital to the genre of science fiction as Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft jumped on the science fiction train in an odd way. Unlike many of the other science fiction writers, he didn't grow up reading H.G. Wells or Jules Verne. He read Edgar Allen Poe, and only read about space in scientific text books. But where other boys growing up saw the potential for adventure out among the stars, the idea of space terrified him. An infinite abyss with countless stars? Where was man's significance in a universe as cold and vast as this?

Combining his existential dread with his love of Poe (and an incredible terror of aquatic life and black people), Lovecraft wrote several short stories between 1917 and 1935 that would change the genre of science fiction forever more by combining science fiction with gothic horror.

His stories dealt with alien lifeforms so gigantic and unknowable that the sight of them was enough to drive man into madness. In "The Call of Cthulhu," H.P. Lovecraft sums up the entire theme of his writing in a few powerful lines:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Lovecraft was not an optimist.

Aside from Great Old Ones and Outer Gods, Lovecraft wrote of alien beings who dwelt outside the constraints of time that could swap minds with a person, aliens living on the planet Pluto who could live forever and travel to new worlds by extracting their brains into machines, and an unknown color that could kill you.

Of all his creations, though, most fascinating are the Elder Things from Lovecraft's novella At the Mountains of Madness (1931). The Elder Things, which set up a city in Antarctica, created life on the planet Earth. The human beings traveling to Antarctica meet not only the remains of their creators, but the Elder Things' secondary creators – the Shoggoth, molten fiends who want nothing more than to destroy.

This story proposes a disturbing prospect that is still being played with decades by countless science fiction storytellers (like Ridley Scott in Prometheus). "What if our creator wasn't a God, but just an advanced alien race?"

Lovecraft kept a tight correspondence with other pulp writers, such as Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard (the creator of Conan the Cimmerian), Robert Bloch (writer of Psycho), and Frank Belknap Long. These writers – and many more – would carry on the tradition of Lovecraft's writing after Lovecraft's death, spreading the themes of what would later be referred to as "The Cthulhu Mythos."

Today, we refer to the genre as Cosmic Horror.

Modernist Science Fiction

Around the same time, the literary movement of Modernism had taken hold of the literary community. Modernist writers focused on capturing the human experience in an effective, moving manner. Most of these writers, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, focused on minimal language and social isolation.

Many science fiction writers of the 1930s found themselves influenced by the influx of planetary romance stories and modernist writings, as well as, toward the middle of the 30s, cosmic horror. These three core influences would lead to the science fiction genre changing from the 30s and 40s onward – a change felt in both the pulps and cinemas.

But the history of science fiction could not have facilitated this change if not for John W. Campbell, who, in the late 1930s, became the main editor of pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction. Campbell took science fiction very seriously, and only published high-quality works that explored the implications of science in a more modern perspective, dealing with human psychology more than merely adventures.

Numerous new science fiction writers started contributing short fiction, leading to a boom of sci-fi in the 1940s. Astounding Science Fiction became one of the leading sources of sci-fi at this time. Campbell published the early works of many great writers.

One of whom was Isaac Asimov.

Isaac Asimov celebrated a long and amazing career in science fiction for many decades. To summarize his accomplishments in a small passage is a disservice to the great writer. But I will try my best.

Asimov was a writer who had grown tired of the tropes and cliches of science fiction. Consistently – across all of his work – he attempted to subvert or alter expectations in the genre.

Automatons and robots had become almost a stock adversary in science fiction, so Asimov, tired of the same old thing, decided to write a series of short stories where robots, by their very programming, could not kill men.

Enter I, Robot (1950), a collection of Asimov's short stories about robots. The name is inspired by Earl and Otto Binder's short story "I, Robot," (1939), which tells the story of a friendly robot willing to serve man. When the robot's master dies in an accident, people accuse the robot of committing the crime, which causes the robot to retaliate. However, after reading Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, the robot refuses to hurt anyone, and deactivates.

Binder's influence is clear throughout Asimov's I, Robot.

In this story, he presented readers with the "Three Laws of Robotics," a simple program to prevent robots from ever killing people.

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

These simple laws make the idea of a "killer robot" impossible, and, thus, forced Asimov to think outside the box. Considering I, Robot is a landmark in the history of science fiction, he clearly succeeded.

When people talk about Asimov, however, they often reference I, Robot and the Foundation series. Starting with Foundation (1953), the story tells of a future space empire. A single scientist named Hari Seldon, using a scientific technique called psycho-history, predicts that the galactic empire is close to its final days, and thus takes the necessary precautions to preserve civilization through two separate sites on either side of the galaxy.

The novel draws heavily from the real-life fall of Rome, as well as the planetary romances of yesteryear. However, rather than have strapping men beat up aliens, Asimov had all his heroes use their wits rather than brawn to escape their problems, making both the conflicts and resolutions far more potent. The saga (which originally ended after three books) proved to be one of the most important sagas in sci-fi.

And, yes, yet another landmark in the history of science fiction influenced George Lucas when making Star Wars.

Asimov is often grouped together with Robert Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke as the "Big Three" writers of science fiction. From the 50s to the end of the 20th century, these three were the most influential, consistently great science fiction writers of all time. Even after his death in 1992, Asimov remains one of the most beloved writers of the science fiction genre.

But as science fiction writers like Asimov depicted visions of the future where science could solve all problems, just as many writers depicted less than optimistic visions of the future. Though, unlike Lovecraft, these writers didn't need to look to the stars to see disaster on the horizon.

Aldous Huxley wrote Brave New World in 1931. Many regard the book to be the first great dystopian novel. While H.G. Wells presented a dying world in The Time Machine, Huxley didn't visit a dying world, but rather a mechanized civilization.

In Brave New World, Huxley presents a future where mankind has become automated, turning people into cogs in a machine to further advance society. He based this model of civilization on the assembly lines in the Ford Motor Company.

His visions of the future – of a world where man is controlled by drugs, sex, and television – rings uncomfortably true in today's age. But, at the time, such concepts were a little outlandish. A little crazy. It wouldn't be until 1949 when a new dystopian novel would be published, one that rang too real in the era sandwiched between WWII and the Cold War.

British satirist George Orwell was never a science fiction writer in the strictest sense of the word. He wrote short stories and essays, for the most part. However, in 1948, the great writer learned he was dying. In his grief, he channelled his cynicism of the world into one masterful volume. One great novel.

1984.

1984 presented a world of hellish, social disarray. Society is dominated by Big Brother. You cannot think ill of Big Brother. You must obey. Every waking moment, you are watched.

1984, at the time, was an example of literary science fiction. Now, however, with regimes like North Korea, it is an uncomfortable reality.

Later on, Ray Bradbury, undeniably one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, would publish a book called Fahrenheit 451 (1953). The book drew heavily from Nazi book burnings and what Bradbury perceived as a desensitization to the rest of the world thanks to the media and television. The book presents a civilization where an authoritarian government has taken to burning any and all books in order to keep humanity ignorant of their lowly condition under their boot – in order to stomp out the idea of resistance.

These three books are what are seen as the tenets of the dystopian genre of science fiction. Each book, beyond being great works of science fiction, are seen as great works of literary fiction.

Throughout the history of science fiction, there is one constant: very few works of sci-fi are taken seriously by the literary elite. These three books transcended those limitations. They are undeniably science fiction, but they struck a cord with literary and mainstream readers due to their more literary and intellectual feel.

And the fact that, unlike Isaac Asimov, Orwell never included robots or space ships.

The Atomic Age of Cinema

But as literary science fiction took off (we will save the accomplishments of Arthur C. Clarke for next time), cinema pushed a very different view of science fiction.

For whatever reason, science fiction cinema from the 1950s took a very different turn. While literary science fiction took a modernist approach, sci-fi films drew from cold war paranoia and the fear of the atomic bomb, combined with a dosage of cosmic horror. Invariably, the vast majority of science fiction cinema came in two forms: alien invasions and giant monsters. Usually, nuclear weapons tied into one or the other somehow.

Many of these movies featured special effects by Ray Harryhausen, a pupil of Willis O'Brien (the special effects wizard behind King Kong and The Lost World). Hayyhausen's stop-motion monsters, appearing in films such as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) and Earth vs. The Flying Saucers (1956), spread the iconography if 1950s sci-fi cinema: monsters, monsters, and more monsters.

Most sci-fi from this era, however, wasn't very good.

Films like Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957), The Giant Claw (1957), and Robot Monster (1953) were notorious failures. While the modern sci-fi fans regard these movies as so-bad-they're-good cult classics, at the time, these films were straight-up failures.

And countless other science fiction films, even worse than being awful, were just forgettable.

To stand out in the history of science fiction, sci-fi films either needed state-of-the-art special effects or offer intelligent social commentary. Thankfully, a few films did the latter.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) presented space pods that replaced sleeping people with identical duplicates, duplicates who worked toward a single, insidious objective. The film is a very clear satire on Cold War paranoia – that all people would lose their individuality in a world run by Communism (or, alternatively, lose their individuality under McCarthy's paranoid rantings).

Godzilla (1954) revealed a great monster that rose from Japan to wreak atomic destruction. Following the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, the Japanese channelled their terror of atomic weaponry into an unstoppable monster.

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1957) features an alien touching down on Earth to issue a warning to humanity to stop using nuclear weapons, only for the government to shoot him down the moment he steps on land. The message for this is obvious.

But arguably most important of all in the history of science fiction going forward was one film called Forbidden Planet (1956). Adapted from the Shakespeare play The Tempest, Forbidden Planet stars Leslie Nielsen (yes, the same one from Airplane!) as a space explorer with a crew of scientists who uncover a strange, new world, and, along the way, seek out new life and civilizations.

Forbidden Planet boldly went where no science fiction film went before.

While the film itself didn't change the world of cinema, it did influence a young man named Gene Roddenberry who took the building blocks of Forbidden Planet, and took them to the next level.

But that discussion will wait for another day. In the next chapter, we will explore a planet of sandworms and spice, a spaceship exploring the farthest reaches of space, an alien intelligence directing the course of human civilization, a hive race straight out of your darkest nightmares, and, yes, maybe we'll talk about Star Wars.

About the Creator

Anthony Gramuglia

Obsessive writer fueled by espresso and drive. Into speculative fiction, old books, and long walks. Follow me at twitter.com/AGramuglia

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.