From Healer to Heathen: The Ever-Changing Evolution of the Witch

The History of the Magic Woman

‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.’ (Exodus 22:18).

As children we were taught that witches were something to be feared. Fairy stories portray them as hook-nosed, green-skinned, wart-covered beasts, who preyed upon the hero to try and foil their plans. But witches were not always inherently evil. The evolution of the magical woman has been one that has blossomed out of control, starting with the very early portrayal of Goddesses and healers, and over time transforming into the pungent, evil beings we’re familiar with within modern literature. Why has such a change occurred? And is there any hope of witches reclaiming their former glory in a society that already has them so ingrained in the role of evil?

Early evidence of witchcraft can be found within Ancient Greek and Roman telling’s of myths. Characters such as Circe and Medea are two examples of women who are polypharmakon, meaning ‘skilled in many herbs.’ Their stories end in tragedy when they use their magical abilities for selfish reasons. Medea, writhe with jealousy, poisons and kills Jason’s new bride after he rejects her love, believing she is the true deserver of his affections after she helped him become victorious within battle. Circe was exiled by her father, Helios, to an island called Aeaea as punishment for murdering her husband after she unlocked his magical potential, only to be betrayed by him falling in love with other nymphs and goddesses (Brown, 2015). What both Circe and Medea have in common is that both of their stories involve seeking vengeance after romantic betrayal. They are the villains within their stories because of the poor decisions they make once they awaken to their powers, consequently placing negative connotations upon the act of witchcraft. Many Greeks feared magic-doers because of tales like Circe’s and Medea’s, and the fear of magic became a way to control the public with the threat of disobedience being punished by something akin to a curse (Cartwright, 2016). However, as the world progressed so did its view on magic, and whilst many were still terrified of it, they also worshipped and praised those worthy of the otherworldly.

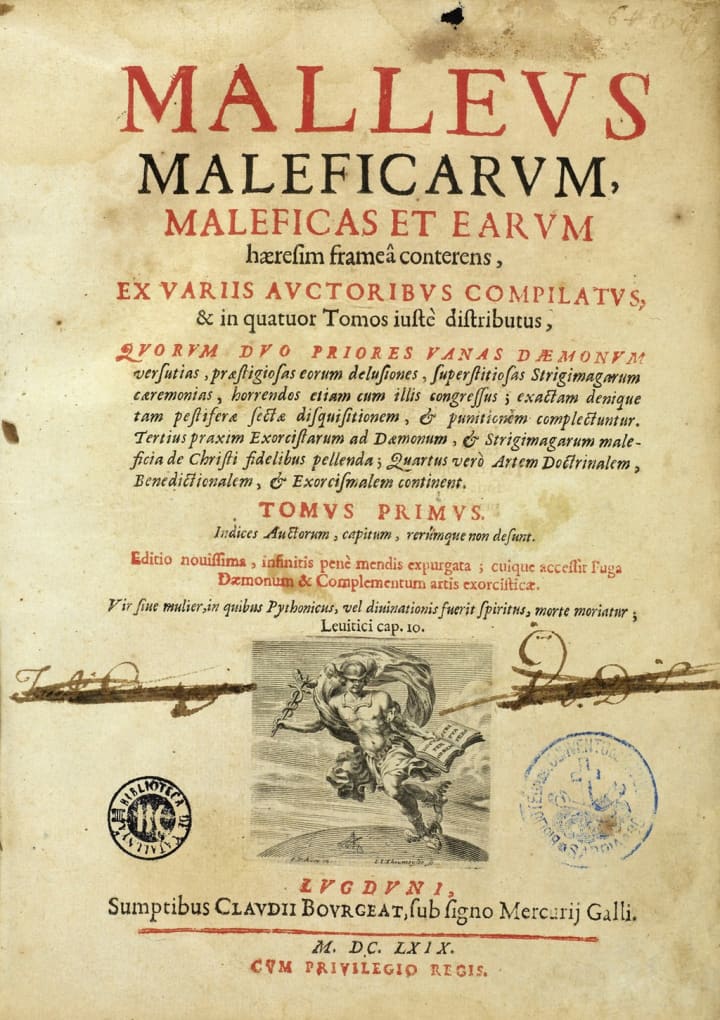

We’re familiar with the legend of King Arthur and his battles against the evil sorceress Morgana, his half-sister who betrays him in her quest for power and the throne of Camelot. Morgana has appeared as the villain in many modern-day retellings of the legend, including the popular BBC TV Show Merlin, wherein she changes from an ally to Arthur once awakening to her magical powers. But originally Morgana wasn’t evil. Known as Morgan le Fay (‘the fairy’) she possessed abilities that aided Arthur through many of his grueling battles. She was known for both her beauty and her power to heal, shapeshift and fly, and was thus a desirable and admirable character within the Arthurian Legends. This telling of Morgan dates back to Geoffrey Monmouth’s Vita Merlini, which was written in the 12th century; the villainization of Morgana didn’t occur until the 15th century telling by Sir Thomas Malory titled Le Morte Darthur,(Calvo Zafra, 2015) wherein her motivations change from that of aiding Arthur to overruling him. The change within Morgana’s character is rather drastic, especially when we acknowledge that the other characters within the legend do not undergo a transformation, including the character of Merlin, another magic user who is never condemned for his powers. The change in Morgana’s perception is one that is inherently misogynistic and can be linked back to the struggles of poverty, education and status within the medieval century. In the middle age’s healthcare was hard to come by unless you had access to money. Many physicians were men who could read and write, and so were a higher class than those living within poverty. Physicians usually served those within the monarchy, or their equivalent, and so the poor were left to solve their own ailments. Within the village there were people, usually women, dubbed as healers who had knowledge passed down to them from their mothers on how to cure ailments with natural ingredients. This information was never written down, as peasants could neither read nor write, and so this wisdom was seen as something inherently magical. These women were essential to the survival of the villages that lived in squalor as it allowed people a chance at survival without shelling out more money than they could afford for a court physician. Morgan le Fey’s original purpose as Arthur’s healer through use of otherworldly powers is almost certainly linked to those medieval healers, and her change in narrative is almost definitely a result of the change in the societal perception of magic thanks to Sprenger and Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum.

The Malleus Maleficarum, released in 1486, is an instructional guide on how to hunt and persecute the act of witchcraft — an issue that became progressively more feared throughout the 15th century. Fearmongering and superstition led to the popularisation of Sprenger and Kramer’s book, wherein people began to associate specific traits with witchcraft, and thanks to biblical influence, witchcraft with that of the devil. The book was split into three parts: part one describes the cooperation between the Devil and his witches; part two details how the witch signs her soul, once belonging to God, to the Devil in exchange for power; part three explains the legal procedures for prosecuting a witch (themystica.com, n.d.). Those most at risk of being suspected of witchcraft were the healer women who had herbalist knowledge, could brew potions or poisons, and who had knowledge of things that they shouldn’t have. Those who possessed ‘otherworldly’ qualities, such as the knowledge to cure ailments, were no longer praised, but were feared as demons, incubi and succubi. People who also exhibited symptoms of what we would in the modern day call auto-immune diseases were accused of witchcraft, as they would be prone to symptoms such as seizures, sore joints, and the inability to speak or communicate properly, which were mistaken for the accused being under a satanic influence (Montague, 2019). Witch trials allowed there to be a link between the unknown and the devil. It was thought that Witchcraft was the Devil’s influence on Earth, and with the rise of Christianity and the decline of Paganism, it is unsurprising that people became frightened of a phenomenon they didn’t understand. The lack of understanding surrounding ailments that today are commonplace led to many vulnerable people being accused without the ability to defend themselves. Of course, many other social and political factors attributed to who was accused. The lack of accurate lie detection and evidence testing may have led to accusations of witchcraft out of jealousy or spite, condemning the accused to suffering wherein they may have pleaded guilty to end their torture. Regardless of how, every instance of a person accused has moulded and shaped the characteristics of the witches we’re familiar with in modern literature. The witch hunts are responsible for the popularisation of the villainization of magical women and, to some extent, men. Literature began to adopt magical prowess as a mechanic for evil, usually linking the powers of women with a motive for sexual promiscuity — something that was also condemned by the Christian religion. Morgan le Fey’s transformation included a darkening of character to include other sins amongst her sorcery, a characteristic likely derived from the Malleus Maleficarum’s description of witches as ‘satanic and sexual abominations’(Kramer and Sprenger, 1486) alongside the false accusations brought on by cheating husbands and jealous wives that lived during the times of the witch trials.

The impact of the Malleus Maleficarum has absorbed its way into popular culture in a variety of ways. Wonder tales we were told as children include witches as the villain, usually vengeful and jealous of the protagonist who possesses qualities they wish they could have. Snow White is a wonderful example of this. Queen Grimhilde is jealous that Snow White will take her place as the fairest in the land and eventually resorts to witchcraft in the shape of a poisoned apple to try and kill her, but as with all tales of good vs evil, good triumphs in the end (Karl and Karl, 1857). Hansel and Gretel also features an evil witch who tries to fatten up, cook and eat the children who have visited her house in the forest, a premise that would strike fear into the heart of any child (Karl and Karl, 1857). And as we progress into adulthood, we’re still likely to consume media that demonises the character of the witch, as this is deemed the traditional role that witches fall into. However, authors that wish to break stereotypes within their writing have begun to take witchcraft back to its herbalist roots to try and redefine the word from one that is evil to one that simply means magical. The Wizard of Oz is famous for introducing us to the Wicked Witch of the West, but many often forget the vital role that Glinda the Good Witch played within the story. Glinda’s character is one that is defined by high femininity, as Pam Grossman writes, ‘her butterfly-bedazzled pageant gown, her honeyed singing.’ Her character affirms old-fashioned ideas about the value of beauty: “Only bad witches are ugly,” which Glinda tells Dorothy upon their first meeting. The story is undoubtedly progressive within its narrative, as the idea of a ‘good witch’ was still a foreign concept to audiences in the 1930’s, but by defining Glinda as good due to her beauty, the Wizard of Oz still perpetuates the stereotype that ugliness and abnormality is equal to evil. It was thought that L. Frank Baum incorporated the idea of a good witch into his work because of feminist writings from the 1890’s that challenged the idea of witchcraft being inherently evil (Grossman, 2019). It is believed that he was an advocate for the reclamation of the witch title, but by adding in such a stereotypical antagonist in the shape of the Wicked Witch of the West, he is still perpetuating the idea that anything that does not conform to our perception of beauty, or ‘goodness’ is inherently evil. The story then becomes a challenge between good and evil, or more specifically, beauty and ugliness. Even the actor who played Glinda preferred to refer to her as ‘The Good Fairy’ rather than a witch (Grossman, 2019) as the word ‘witch’ carries far too many grotesque connotations. However, Baum’s work was a step in the right direction in terms of clearing the name of magical woman within literary terms. It shaped the path for other authors to explore the possibilities that witchcraft could hold within storytelling beyond the realms of adversity.

V.E. Schwab’s book The Near Witch is a grand example of modern literature that pushes the stereotype boundaries that we’re familiar with. The book features a character called Cole, a male witch who is misunderstood to be evil even though he’s trying to help to save a village that is under attack by an angry spirit. Not only does this subvert the traditional gender that we would usually assign to a witch, but by allowing Cole to act as a steady positive influence within the main character, Lexi’s, life, the book allows the reader to empathise with him, and view the act of witchcraft within a different light. In the novel Cole says, ‘My mother was afraid. Not of me, I don’t think, but for me. She told me people didn’t understand witches, and so they feared them, and she didn’t want them to be afraid of me’ (V. E. Schwab, 2011). Schwab does an excellent job of incorporating the theme of the witch trials into the novel by having the townsfolk hunt Cole without any evidence, aside from him being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Schwab humanises Cole by having him talk of his mother’s fears, and by allowing the reader to understand that he’s misunderstood in the society he lives in. It encourages the reader to cheer for a witch who is, for once, the underdog of the story.

Madeline Miller also accomplishes this with her interpretation of the Circe myth. She writes Circe as a trodden-down underdog, delving deep into what happened before she became the witch of Aeaea. Miller focuses on the theme of personal growth. Once Circe awakens to her powers she begins to value herself a lot more, changing her attitude from, ‘The thought was this: that all my life had been murk and depths, but I was not a part of that dark water. I was a creature within it,’ wherein she has little hope for a prosperous life, to, “Witches are not so delicate.” Miller’s version portrays magic as a way to achieve goals that otherwise wouldn’t be accessible. We do not feel as though Circe is the villain as we do with the original Greek myth; we empathise with her because she is written to be a relatable character. She makes mistakes, but pays the consequences, and eventually uses her magical prowess to strive towards good instead of evil. In this way, Miller is reclaiming an older tale to support a more modern view — that witchcraft is not inherently bad.

The view of witches throughout society will always be a continuously evolving idea, seeming to rocket back and forth between good and evil. At the moment we are in the transition of witches reclaiming their power to become the heroes of the story, but it is likely that, over time, we will see them transition from that of reclaimed nobility back to the role of the primary villain. What we cannot deny is that magical women, no matter their morality, will always play an important role within storytelling, and will always continue to delight, excite or anger those who consume the media that they are in.

Bibliography:

Brown, S. (2015). Potions and Poisons: Classical Ancestors of the Wicked Witch, Part 2. [online] The Getty Iris. Available at: https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/potions-and-poisons-classical-ancestors-of-the-wicked-witch-part-2/ [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

Calvo Zafra, L. (2015). The Female Figure as the Antagonist in the Arthurian World: the Role of Morgan le Fay in Thomas Malory´s Morte Darthur.

Calvo Zafra, L. (2015). The Female Figure as the Antagonist in the Arthurian World: the Role of Morgan le Fay in Thomas Malory´s Morte Darthur.

Cartwright, M. (2016). Magic in Ancient Greece. [online] Ancient History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.ancient.eu/article/926/magic-in-ancient-greece/ [Accessed 23 Dec. 2019].

Cobb, M. (2019). Morgan le Fay: how Arthurian legend turned a powerful woman from healer to villain. [online] The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/morgan-le-fay-how-arthurian-legend-turned-a-powerful-woman-from-healer-to-villain-109928 [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

Exodus 22:18, Holy Bible: King James Version

Faust. (n.d.). Christian views on witchcraft. [online] Available at: https://www.faust.com/legend/christian-views-on-witchcraft/ [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

Grossman, P. (2019). ‘The Wizard of Oz’ Invented the ‘Good Witch’. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/08/80-years-ago-wizard-oz-invented-good-witch-glinda/596749/ [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

Hale, J., Higginson, J., Green, B., Allen, J. and Eliot, B. (1702). A modest enquiry into the nature of witchcraft. Boston in N.E.: Printed by B. Green, and J. Allen, for Benjamin Eliot under the town House.

History.com Editors. (2017). History of Witches. [online] HISTORY. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/folklore/history-of-witches [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

Horowitz, M. (2014). Opinion | The Persecution of Witches, 21st-Century Style. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/05/opinion/the-persecution-of-witches-21st-century-style.html [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

Karl, J. and Karl, W. (1857). Grimm 053: Little Snow-White. [online] Children’s and Household Tales — Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Available at: https://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm053.html [Accessed 20 Dec. 2019].

Karl, J. and Karl, W. (1857). Grimm 053: Little Snow-White. [online] Children’s and Household Tales — Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Available at: https://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm053.html [Accessed 20 Dec. 2019].

Merlin (2008), BBC One, 20th September

Miller, M. (2019). Circe. London: Bloomsbury.

Montague, J. (2019). Can an auto-immune illness explain the Salem witch trials?. [online] Bbc.com. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20181221-can-an-auto-immune-illness-explain-the-salem-witch-trials [Accessed 21 Dec. 2019].

Raymond A. Anselment, “Katherine Paston and Brilliana Harley: Maternal Letters and the Genre of Mother’s Advice,” Studies in Philology 101, no. 4

Tatlock, J. (1943). Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini. Speculum,18(3), 265–287. doi:10.2307/2853704

The Conversation. (2015). A feminist nightmare: how fear of women haunts our earliest myths. [online] Available at: http://theconversation.com/a-feminist-nightmare-how-fear-of-women-haunts-our-earliest-myths-37789 [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

The Guardian. (2012). Why are wizards better than witches?. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2012/jul/10/weekly-notes-queries-female-wizards [Accessed 27 Nov. 2019].

Themystica.com. (n.d.). Malleus Maleficarum. [online] Available at: https://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/m/malleus_maleficarum.htm [Accessed 20 Dec. 2019].

Thank you for reading!

About the Creator

Jade Hadfield

A writer by both profession and passion. Sharing my stories about mental health, and my journey to becoming a better writer.

Facebook: @jfhadfieldwriter

Instagram: @jfhadfield

Twitter: @jfhadfield

Fiverr: https://www.fiverr.com/jadehadfield

Comments (1)

Love this and also that you included a bibliography 😍😍