Finding Aliens ‘Only a Matter of Time’

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence was begun 60 years ago by a young American astronomer named Frank Drake; he’s still confident extraterrestrials abound.

LESS THAN A MONTH before turning 30, Frank Drake flipped a switch and started listening to the stars. It was 8 April 1960, and Project Ozma — the first ever SETI search — had begun.

And although 60 years have passed with no clear evidence of extraterrestrials out there, Drake remains convinced that humanity has barely scratched the surface. The search has barely begun, he says.

His influence in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence — or SETI, as it is commonly known — has been enormous. Drake not only conducted the first radio search for civilisations beyond Earth, he helped Carl Sagan design the plaque in 1972 that was attached to the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft, the first of humanity’s emissaries to leave the Solar System.

In 1974, to mark the reopening of the Arecibo radio dish in Puerto Rico — then the world’s largest — he transmitted humanity’s first interstellar message: a three-minute binary signal with a pictogram of DNA, a graphic of the Solar System, and 10 other items meant to describe our world to extraterrestrials.

The message wasn’t much to look at, and Drake didn’t expect a reply anytime soon: it was aimed at the globular star cluster M13 some 22,200 light years away. Although very far away, the signal should have been strong enough to be detected by an alien civilisation — assuming it just happened to be pointing an Arecibo-sized radio telescope in our direction.

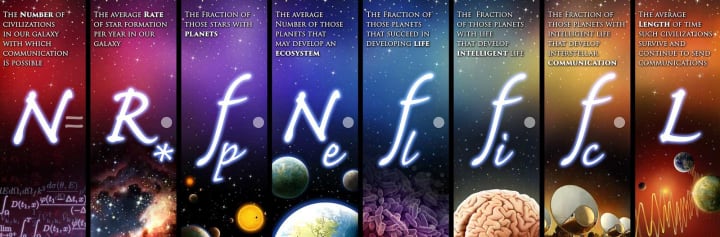

But Drake is best known for creating the enormously influential equation that bears his name — the Drake Equation. Devised in 1961 ahead of a conference on the SETI, it is simple yet incredibly powerful. It seeks to quantify the unquantifiable: the potential number of extraterrestrial civilisations in our galaxy. And it is still used today.

The following is an interview I did with the SETI pioneer.

When you talk about your famous equation, what do you think now, all those years later?

People keep asking, ‘should the equation be changed?’ The answer is no. It still works. It’s still correct.

The only thing that’s changed is the numbers we put into it. When I first invented the equation, we had to guess some of the factors in the equation. A lot of those have now been established through observation. For instance, the fraction of stars that have planets — we know now that it is more than half. The number of possible habitable planets in a system is higher than we thought in the past — because we’ve discovered things such as oceans in places we thought they couldn’t exist, such as Europa [Jupiter’s moon].

So the equation is still good. The numbers we put in it are getting more accurate all the time. There are still some big unknowns. One is the fraction of civilisations that actually develop technology. The other — a big factor — is the longevity, the ‘L-factor’ [in the equation], which we will not know until we’ve discovered some other civilisations.

Have you been surprised by some of the developments? For example, the number of exoplanets out there?

Oh yeah. Well, surprised in a good way. We used to make estimates based on very indirect observations of the rotations of planets, and theoretical models. Well, now we have actual observational confirmation that those things were correct.

The observations have all supported the idea that there is a lot of life in the universe. What they show is that what happened in the Solar System was not unusual. It did not require any special circumstances, or any freak situations, and therefore what happened here should have happened in many places, and that includes the evolution of an intelligent, technology-using creature.

What do you think would be the impact on humanity if we finally find an alien civilisation?

It will have a tremendous impact because almost any civilisation we find will be much older than our own. They will have much more experience. Much more knowledge, technical and scientific. And that will benefit us greatly. And we will learn ways to have a higher quality of life on Earth which would otherwise take us perhaps hundreds of years of expensive research to learn, to identify ourselves.

It’s been 60 years since Project Ozma. You were quite excited in the early years when you began. Has your point-of-view changed? Or your impressions changed about the likelihood of finding intelligent civilisations?

No. I’ve always known it was very improbable. If you put the most optimistic figures in the Drake Equation, it leads you to conclude that probably only one in 10 million stars has a detectable signal. We haven’t searched that many stars.

There’s also the problem of we don’t know what frequency to look at. We’re presently still limited to not searching all reasonable frequencies.

Also, the signals may be transient, they may not be ‘on’ all the time, so we need to search tens of millions of stars for long periods of time on a wide band of frequencies, before we’ll have a good chance of succeeding. And we haven’t done that.

So, if anything, you now appreciate how much harder the problem is?

We knew it was hard in the beginning, now it’s clear that we were right. It is hard.

Now that 60 years have gone by, is your overall attitude still one of optimism? Or is it optimism weighed down with some frustration?

Well, it’s optimism with reality that it’s going to take a long, long time to succeed. But we will succeed.

Can you venture a time frame?

That is very difficult to do. It depends on how many resources we put into it. Which depends on the will of governments, and funding sources. Which has been changing greatly from year to year. I’m guessing 20 to 30 years. ‘Guess’ is the right word.

The optimism about the likelihood of finding extraterrestrial life has somewhat declined. Do you think that this might impair the search?

Well, if the interest declines, that’s bad. But I don’t think it has declined. There’s a tremendous interest in science-fiction movies. The most popular movies of all time, except for Titanic, were all science-fiction movies. There’s a tremendous interest in the general public in life in space.

But the general public also realises that finding life is going to be difficult, and that in a way we [SETI researchers] have hurt ourselves, by raising false expectations.

NASA does that too. They say that every mission they send is going to determine whether there is life on some place, and no mission they’ve ever sent could find that out. And the public begins to become cynical about claims of ‘Oh, something’s gonna detect life in space. Well, we’ve heard that before, and it was not true.’

It’s a problem we have: the media glorifies something, glorifies our search more than it deserves. Our search is very limited. The chances of success are small. Often the media don’t make that clear.

When we say ‘60 years of searching’ — it’s really, if you tally it all up, only a few thousand hours. Isn’t it?

Well, it’s more than that. Actually, it’s a lot more than that, because of these searches that are continuously watching, such as SETI@Home, conducted by Harvard University. The researchers there just let the Earth rotate, and they can say, ‘well, we looked at thousands of stars’.

In fact, they look at any given star for 10 seconds, and they look down a very narrow band of frequencies, so it’s very misleading. They say they’ve looked at a thousand stars — but they’ve looked at each one for a few seconds, at a few frequencies. Well… that hardly counts.

In some searches, such as Project Phoenix, they did look for a long time at stars, and a wide band of frequencies, and that was a much more thorough search. The amount of searching we’ve done is highly variable in its quality. A lot of it is almost worthless.

That’s because we don’t know what will succeed, therefore we’re trying so many different strategies?

That’s right. And also, many of the searches have been very weak in that they have no immediate follow-up. For instance, in the Harvard search, with SETI@Home, the data is recorded but is not analysed for, typically, at least days, or usually weeks, later.

And they will find something that looks like a signal. Then they go back and look at that place in the sky and that frequency and there’s nothing there. Well, that tells you nothing. It could be that these signals are present only for 10 minutes every month or so, and so the fact that there isn’t an immediate follow-up is very damaging. It greatly reduces your chances of success.

The only search that’s been able to follow-up immediately is our search [run by the SETI Institute]. And that’s because we have enough money to have people present. And it’s a matter of money.

That’s important, isn’t it? Being able to follow-up?

It’s no good detecting a signal if you can’t identify it immediately. And it needs to be immediately, because the signal may be transient. It may be briefly there. And there are a lot of scenarios you can concoct which would have all the signals being transient. In our searches [that] we followed up — none of the candidates has proved to be extraterrestrial. Some searches have hundreds of unexplained signals that we’ll never know what they are.

Of the different strategies that have been used or suggested — radio signals, optical signals, etc — is there one that you are more confident about?

That’s a hard one. Optical is much more detectable, because of these very powerful lasers. However, there’s a big down side to that, as they are much more detectable if the light pulse is focused by a very large reflector, which means that the amount of space that sees that pulse is very, very small. In fact, they have to be intentionally aiming it at you.

So, the optical only works if other civilisations are intentionally trying to signal [us]. Which would mean they know about our system, and where our planets are. That raises a whole new issue, which is whether there is altruism in the universe.

What do you suspect is the detectable number of civilisations in the galaxy today, knowing what we know now about how many exoplanets there are?

Ten thousand. That number is largely based on a guess as to the longevity [of a civilisation] being about 10,000 years. It’s totally a guess, because it’s far beyond our experience.

But that’s now? Detectable now?

Right now.

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com | https://bit.ly/3kIF1SO

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.