The eminent physicist Charles H. Bennett is reflecting on life in the universe. It is possible, says Bennett, that we live in the best of worlds. If, on the other hand, earthquakes, pestilence, and wars seem to us proof of the absurdity of existence, we are mistaken. Behind every misfortune there is a rationale, an unguessed divine intention. This, more or less, is how the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz saw the world. In his view, the universe, like a magnificent instrument, was perfectly tuned to the needs of intelligent life, of us grateful observers.

Arthur Schopenhauer, on the other hand, thought it could not be worse. The world is as bad as it can be. It depends on so many parameters, temperatures, pressures and chemical compositions, that its very existence seems to be a phenomenon of the extreme kind. That is — a change in even one of them would entail the impossibility of life (as we know it) continuing. Born in 1943, Bennett, with all his achievements in physics and information theory, the inventor of teleportation and quantum cryptography, for several decades an employee of The Thomas J. Watson Research Center (IBM’s research headquarters), a man of many talents, including musical, would have no chance to exist. Neither would his tin boat.

Inflationary universes

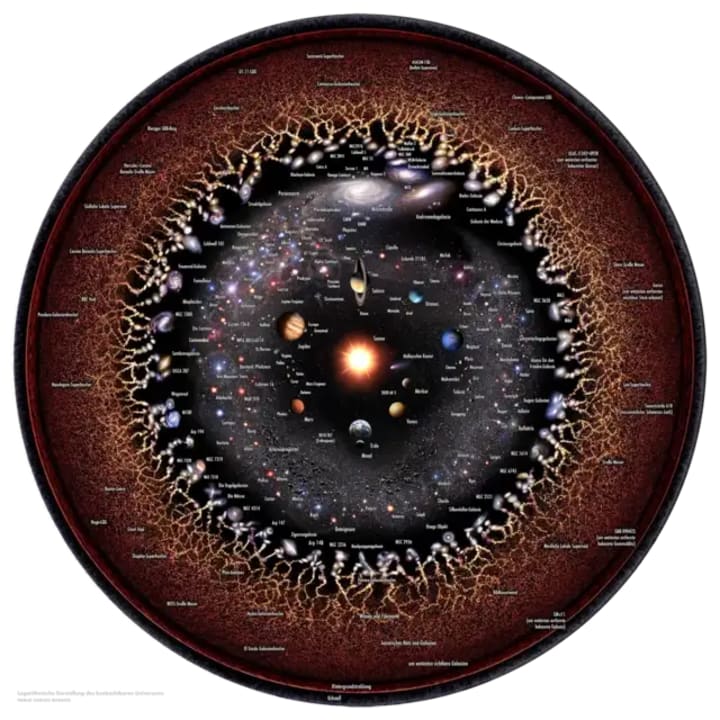

So what for life is this world-universe of ours? The answer to this question is greatly complicated by the fact that, as cosmologists commonly believe, we see only a tiny fraction of it.

Of course, we are not entirely helpless in (somewhat) similar situations. We have effective statistical methods, to mention the little-known problem of the German tank. Preparing for the landing in Normandy, the Allies tried to estimate the number of German machines in Europe. The reports provided by spies were either inconsistent or untrustworthy. So mathematicians suggested that they take a closer look at the serial numbers of tanks destroyed or captured in battle. The Nazis numbered their parts in a very orderly fashion. Knowing the number of copies found, the maximum serial number read, the Allies were able to estimate the number of tanks produced monthly by the Germans with astonishing accuracy, almost to the piece. — Unfortunately, talking about us, humanity, and the known universe is a bit like considering German tanks — except that we only have one tank, Bennett notes, correcting his capo. But maybe not necessarily?

One of the most promising cosmological theories, inflationary cosmology, leads us to believe that behind the ever-escaping horizon, inaccessible to our observations, lie many disparate planetary systems, many more than those in the visible region of the cosmos. Some worlds are habitable, like ours, and others are not. Even if Schopenhauer, the virtuoso of pessimism, were right, and life were teetering on the brink of extinction, such a situation would apply only to the area closest to us. But globally, in the entire universe, life would most likely remain unthreatened and take all possible forms, more or less as Leibniz postulated. Unluckily, such a model gives rise to dreamy specters, vacuum fluctuations called Boltzmann brains. These seemingly preposterous artifacts of the industrial revolution greatly complicate consideration of what is typical and what is not in the cosmos.

Big and small fluctuations

It all started with the steam engine and the paradigm of increasing efficiency. Looking for ways to make steam engines more efficient, thermodynamics, the science of thermal (but not only) transformations, was invented (sort of). Scientists introduced the concept of entropy, a measure of disorder. They observed that in any closed system, such as a steam-filled cylinder, disorder increases until it reaches a maximum. It continues until large-scale activity ceases and the only movement is chaotic collisions of molecules. — “Such a state is called heat death,” says Bennett.

The problem of possible heat death could also, in theory, affect our planet.

“If you were to enclose the Earth in a box, blocking out sunlight and the outflow of radiation from its surface, eventually everything would reach a uniform temperature. It would be dark, the winds would cease, the ocean currents would stop flowing. Everyone would die, and the planet would become dead forever. Heat death is such a Godless version of hell,” Bennett says, paddling steadily. — “But even in this dullest of places, after an unimaginably long time, extraordinary things can happen”, he adds.

Once the particles scattered in it (Boltzman’s reasoning can be extended to elementary particles) have arranged themselves in all possible ways, run through all possible configurations of positions, who knows, maybe they will start doing what they once did already? — Maybe they will suddenly, accidentally arrange themselves into the Earth from before the great deadness, alive and flourishing, without any negative symptoms of being kept in a closed box? The entire history of stagnation will be erased and replaced by the illusion of another history, the illusion that it was subject to slow evolution rather than appearing in an instant. The possible history will be different from the real one.

This is more or less what Ludwig Boltzmann was thinking about at the end of the nineteenth century, looking for an answer to the question of why, with such a long history, the world around us has surprisingly little entropy. Perhaps we live in an area of fluctuations, anomalies, the great Austrian scientist observed, in an oasis of order surrounded by a dead cosmos? Like, without looking for a metaphor far away, Charles H. Bennett in a wobbly boat in the middle of a lake.

Of course, great anomalies have it that they happen mostly in theory. Yes, a dead universe can suddenly awaken, along with all those structures we believe exist, including our brains and the brains of all our neighbors, the inhabitants of the entire world and our Galaxy and other galaxies. Much more likely, however, is a small fluctuation resulting in nothing more than a brain suspended in a cosmic void dreaming of the existence of the universe. —

“Illusory universes are much rarer than individual hallucinations”, says Bennett.

“It is a very subversive idea,” he adds, “that instead of a great fluctuation involving the whole world as it is, we should speak of a much smaller fluctuation. Its product is only your brain in its present form. It contains the image of myself, the memories of events that never happened, the baggage of the knowledge of mankind, the achievements of science based on observations of phenomena that did not happen. This is what we call Boltzmann’s brain. Of course, most scientists would be happy to reject this idea. Unfortunately, it’s hard to find a good reason for that,” says Bennett, turning his hat at a right angle. — Well, why don’t you row now?

A cosmologist’s nightmare

The fear that everything is a dream may seem exaggerated, but it is not. It has potentially huge implications in cosmology. For there are many indications that the universe is expanding, moving toward, perhaps, a state of heat death. It’s just that while it can only reach the terminal state once, it can dream of a fictional past infinitely many times. And perhaps that is what it is doing now?

Physicists today further believe that at the edge of our expanding universe, out of the vacuum, particles are being created in a completely spontaneous fashion that could become the building blocks of Boltzmann’s brains. Or not so much can as are becoming — and constantly, infinitely many times. It gets even worse. Many cosmologists believe that the universe is not only subject to inflation, but that it is “rebounding” into countless ramifications. The fear that there are far more Boltzmann brains in the universe than those considered ordinary borders on certainty. This is a cosmologist’s worst (perhaps) nightmare.

It is possible that we are a hallucination, a dream of a jelly gliding in a vacuum. We could live with that somehow. The worrying thing is that Boltzmann’s idea of brains is, as physicist and dark matter specialist Sean Carroll believes, “cognitively unstable.” For in doing Earth science, we tacitly assume that we are typical inhabitants of the cosmos, that our laws apply even in places where our telescopes cannot look. But maybe we are not typical at all? Maybe the laws we discover are merely local, limited to a small corner of the universe? This would mean that our scientific method leads to the conclusion that Boltzmann brains are common in the cosmos and that we are an illusion — so all this laboriously constructed knowledge must be rejected. Or put another way: the data we collect suggests that it cannot be relied upon. It is impossible to do science responsibly in such paradoxical circumstances.

Of course, attempts are being made to stabilize (cognitively) this situation. Don Page, a colleague of Stephen Hawking, suggests that the expanding universe has a built-in self-destruct mechanism, triggered when Boltzmann brains begin to dominate others. In about 20 billion years, the universe will reset itself and start over. What if the universe is branching out? From the calculations of Andrej Linde, co-discoverer of inflationary theory, it seems to follow that in such a multiverse the supply of Boltzmann brains will always exceed the supply of “ordinary” brains. Unfortunately, Linde admits, we are like children in a fog in this area. It is not easy to think about the probabilities of events occurring an infinite number of times in an infinite, budding spacetime.

How then is it? Is it possible to say something meaningful — and with confidence — about life, the universe, and everything else? Carroll thinks so, if we use Boltzmann’s brains as a criterion for choosing future cosmological models. If the new description of the universe we construct, and there are many being constructed, suggests an overproduction of these suspect artifacts dating back to the nineteenth century, then it is to be rejected. Boltzmann’s brains would thus become a useful wake-up call, a tool for eliminating questionable cosmological models. And if it’s a misguided hypothesis? Well, then even Schopenhauer must seem optimistic….

“Then there would be nothing but a cubic meter of matter, which lasts for a few seconds and after a few more will be gone, because the cosmic vacuum is not a hospitable place for life,” says Charles H. Bennett.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.