Nobody can hear a scream in the vacuum of space, or so they say. But I can hear myself. I hear every breath I take, every creak of my bad knee, every belch and sniffle, every gurgle of my stomach, which is still fighting to adjust to the dehydrated food. Space; painfully empty and painfully loud at the same time.

Roz tells me I’ve been in transit for ten days now. She sits in front of the camera, her black hair wild and curly, green eyes flickering through thousands of miles of space. “Pretty soon, Mars will be far behind you,” she says.

I lean back in the comms chair, my feet up on one of the station desks. The console rings the front part of the room in a half-U. There are four workstations, plus the pilot’s seat. From here, I can do anything from change our trajectory to send out a deep space message signal. There is also a viewing window. I haven’t been able to see the Earth since day three.

“Doll?” Roz says. “We found out this morning that Shelly’s signals have stopped updating.”

I put my feet down. “Completely?”

“They’re still broadcasting, but the pattern is no longer changing.” She leans in closer to the camera, crossing her arms across the company issued uniform. It’s maroon colored, a similar fit to the one I’m in. “How are you feeling about Mars?”

I look out. Most Academy graduates will never go anywhere beyond the moon. About ten percent have been to Mars. The only other group that’s gone beyond Mars is Shelly’s and now me. “Rather be there than on the ground,” I tell her.

I stare at the screen, the tiny, pixelated grains, the grey of the command room behind her. There are days when I think everything is going to be okay and I’m going to come out of this fine. I’ll get Shelly and we’ll come back safe, maybe start a life together somewhere. Other days, seeing nothing but space and stars and darkness for miles, I know I can’t return to anything I’ve ever known after this.

+

I play Mendelssohn over the speakers. For a tin can built to resist the pressures of space, the living console has great acoustics. The metal walls have been painted over in beige and dark blue to combat some of the sterility of the space. The florescent lights are twenty times brighter than anything back home on Earth. Pretending to be ambient light. It’s funny. I never forget where I am, even with the viewing window closed.

I enter the R-15's crew files and display them on the large screen in front of me.

The pilot was marked dead on day fifty-four, just three days after they arrived at the outskirts of Saturn. That’s where the logs get sketchy. Whereas all four of them wrote detailed daily notes, they then become sporadic and terse. Even Shelly who is normally so thorough forgot to continue her updates, marking only the first death, then the second.

I turn up the volume of the music and begin opening a channel into space, targeting the satellite just off one of the moons of Saturn, the one I think is closest to Shelly.

“R-15, this is R-16. We’re just passing Mars now.”

I pull up the personnel file they’ve given me of Shelly on my tablet. Her picture is standard – blue uniform, her blonde hair cut just below her ears. The lighting on the photo is good, evening out the wrinkles near her mouth and eyes. I touch the picture with the pad of a finger.

“I’ve rerouted and will pass through the moons of Jupiter to save time. It’ll shave off two days or more if all goes well.” I exhale and lean back in the seat. The shuttle wobbles, evens out. “I’m confident I’ll get there under the expected timeframe,” I tell her, then hesitate. “You’re not forgotten.”

+

“This is a suicide mission,” the Admiral told me when I was prepping for this trip. He stood above me as I finished a set of a hundred pushups. My neck burned; it was like he was looking straight through me.

“We have an obligation to seek them out,” I said carefully, through deep breaths.

“We don’t even know if they’re all alive.”

A bead of sweat snuck down my chest, beading into my bra. There was no one else in the gym with us, though I was sure at least six different cameras were recording us. “It shouldn’t matter. They sent a distress signal.”

“Your odds are a thousand to one.”

I stood, wiping my hands on my pants. “I’ll take those odds.”

He was quiet for a long time. I went to the leg machine and started pumping. The gym was filled with cool, filtered air. It sent my skin pebbling all over. “What’s in it for you?” he finally asked. “I mean, really?”

I thought of Shelly’s hair, the birthmark on her right breast, the way she used to look at me early in the morning before she’d race off to teach at the Academy. My knee twinged; I pushed through it. “Fame and fortune, Admiral. What else?”

+

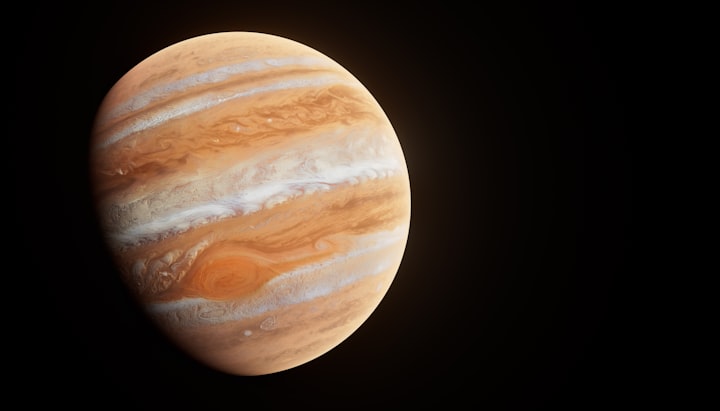

The next few weeks pass slowly. I exercise in the afternoons on the holodeck-treadmill, running along the rim trail of the Grand Canyon, the red dust on the screens around me like the red dust of Mars. I open the control deck viewing window and leave it like that when Jupiter comes into view. From here, the swirling mass of atmosphere looks silver and yellow, almost glittering as it spins.

Eventually, the big planet recedes. The screen goes blank and black. I start waking up in the middle of the night in a panic, reaching for Shelly but she is millions of miles away still. By day 49, I wake up feeling sick and weary. My chest is tight. I look out the viewing window in my bedroom, expecting to be greeted by the same endless vacuum of space.

That’s when I see it.

Saturn.

+

The R-15 rests in chunks. I never thought that was possible for a spacecraft, but it’s all over the place – the thrusters detached from the living quarters, the helm crumpled like it’s hit something solid, maybe an asteroid. One of the mess hall chairs is even floating near the port side, or what I think must’ve been the port side.

As expected, scanners confirm that Shelly is not there.

I spend a good ten hours scanning the nearby moons until I find one with an irregular energy pattern. It’s a satellite moon; pocked with deep craters like acne, all covered in shadows. It looks like Earth’s moon but rougher and more jagged. Viewing it sends a tickle of something up my spine. I send one last message to Shelly.

“I’m coming,” I tell her. “Just hold on a little longer.”

+

Space smells like the inside of a microwave that hasn’t been cleaned in a long time, especially here in the mobile shuttle. It’s all around me as I navigate through the R-15’s debris, headed for the small moon, just barely visible at the edge of the viewing window. The tension that was hidden deep inside me when I left for Saturn is now in my chest, warm like a sip of hot tea.

The moon is shrouded by debris – not the R-15’s, but something else. It makes weaving through things difficult. I dodge and slow. The engine groans, unaccustomed to the spurts of power I throttle into it then pull back on.

By the time I drop into orbit my chest is on fire. The moon is dark, but there is something electrical on the surface. Sparks of light flicker and then disappear, like fireflies. Shuttle scans of the surface are unable to identify what they are.

I open a message to Roz. “Electrical interference on the surface,” I tell her. “This could be the reason Shelly stopped transmitting. I might lose connection once I arrive.”

The shuttle jerks. The microwave scent increases, and it sends my senses into overdrive. Where is Shelly? Growing closer to the moon, I expect to see her shuttle somewhere, a blip of silver amongst the grey, rocky terrain, but there is nothing.

Eventually, the scanners pick up on something manmade inside one of the craters. It’s too small to be a shuttle. I zoom in closer, but the cameras aren’t strong enough to show all the details. I send one last ping to Roz – my intended location – as something sparks just outside the shuttle, and the power goes completely out.

+

My shuttle emergency lands only several meters from the contraption on the moon’s surface. After the dust settles, I change into a spacesuit. All my controls are down except emergency power, which is operated by an iridium generator. Without the overhead lights on, I’m reminded of just exactly how dark space is.

There’s no time to get over the shock. Calculations from Houston show that if Shelly made it out in one of her escape pods, she will be down to her last rations. She’ll be dehydrated, disoriented. Not herself. She needs me now, regardless of all that’s happened between us.

I open the shuttle doors and then am met with the vastness of an atmosphere that is the complete opposite of Earth’s. It presses against my suit, sucking me into the ground. The smell grows; I should not be able to smell anything through the suit and headpiece.

It’s hard to navigate around the pockets of broken earth. The manmade structure looks like one of the emergency pods that’s been expanded into a crisis shelter. It stretches across the planet’s surface in a lean rectangle. Hard to construct in its entirety alone, but not impossible. If anyone could do it, it would be Shelly.

I press forward one step at a time. It’s hard to see through the headpiece, which blocks the view above me. It’s not like it was on Earth’s moon during my first visit. There, I could see space stretching on forever and ever. Here, the atmosphere is hazy. Something lingers several meters up from the planet’s surface, like fog but less dense.

The crisis shelter has an unlocked decompression chamber. I enter it, then am hit with a spurt of tight, raw air. My heart beats fast, and my hands are sweating. Fifty-one days in space. Now I’m here. Right on the precipice.

Decomp ends. I reach out to open the main entrance door, but it opens before I can touch the air lock. Inside, it’s dark, and hard to see. A metal taste fills my mouth. I take off the headpiece just as Shelly’s blonde hair comes into view. She’s in her uniform, just like her picture, except the skin under her eyes is dark. She’s little – a good six inches shorter than me. Compact, but curvy, even though she’s skinner now than before. “I got your messages,” she says. “You shouldn’t have come here.”

+

Shelly doesn’t let me hug her, even though that’s all I want to do – pull her into me, smother my face in her chest. Up close, in the main space of the crisis shelter, I can see what the time alone has done to her. Her hair is stained by sweat. There is a long, healing cut on the back of her left hand.

“Your shuttle won’t start again.”

“Says who? I’ll get it going.”

“It won’t because of the Flippers,” she says, then heads to a hastily set up table which illuminates a holo-map, settling on a piece of bulky compartment luggage. “That’s why I got stuck.”

“I don’t see a shuttle.”

“It’s in pieces,” she says. “They hit me in the air.”

She runs her hands over the holo-map of the planet. She’s marked all the craters, places where the “Flippers” – whatever those are – congregate. Her back is to me, and without thinking, I place my hands on her shoulders like I used to do so much, back when she was working all the time, before I graduated from the Academy, or any of the bad things bristled up between us. Her body is warm. Not hot, but clammy. I want so badly to pull her into me. “Let’s get in the shuttle,” I say. “I have supplies.”

“We can’t.”

“Let’s try?”

“No,” she says. “It’s dangerous.”

I let my hand dip to her chest, laying it just over her heart. It beats, slow and steady, the one thing about her that has not changed after all these weeks.

+

The Flippers are exactly what they sound like – creatures that flip energy inside out, which Shelly says is what creates their electrified appearance and the haze that lingers just above the planet’s surface. “They shocked me hard the first time I went out in the suit,” she says, and I finally notice how downcast her eyes are. “You didn’t see any?”

I tell her there were none around the shuttle.

“Why?” she asks. “Is there a different energy source in there?”

We go back and forth for at least thirty minutes before she agrees to pack up the few remaining helpful items she has and move to the shuttle. “It’ll get stuck,” she keeps saying. “That’s what happened with the R-15 shuttle.”

A light in the back of the crisis shelter wavers. “It was your eyes that made me fall in love with you,” I say. “Did I ever tell you that?”

She rolls those eyes, the green ones that have always held so much pep. They’re tired now, but still, beneath them somewhere is this hard burning energy, this thing that cannot be extinguished no matter what happens to her.

+

Once, when things were the worst between us, Shelly shoved me out of her car while it was in motion. We had been arguing the whole ride in and were going slow – just cruising into the Academy parking lot – when she slammed her hands against the wheel. “If you don’t get the hell out of my car right now, I swear to God, Doll.”

She’d never cursed in front of me before. I told her that if she loved me, it wouldn’t matter what her colleagues said. Then she reached around me, opened the door, and tipped me out of it. I hit the pavement hard, and when she finally parked and came over to me, she was crying. “I have to focus,” she kept saying. “I have to focus to be the best here, and I can’t focus when you’re around me.”

By the time she reached Commander status, I was sleeping on the couch at my best friend’s most nights, waking up early for class, drinking my superfood smoothies, sure of all that was ahead of me except Shelly, this one misnomer, the most career-damning person I ever could’ve fallen for.

+

The Flippers stay far from me. All that surfaces on the short walk from the crisis shelter to the shuttle is the sound of my own breathing reflected in the giant headpiece. Now, with Shelly just ahead of me, it feels less menacing to hear the inside of my own body.

Inside the shuttle, Shelly goes first to the particle-shower. There’s not enough power for her to get her whole body, so she just scans it over her hair and armpits. I dig out the rations and open the dehydrated cupcake I lugged several million miles. “I could do with a steak and onions,” she tells me, even though she only ever ate salads back on Earth.

“The proper response is thank you,” I say. “You seem to have forgotten is that this was a suicide mission.”

She shakes her head. “I never doubted you’d make it here.”

I sit down at the pilot’s seat, about to ask her if the Flippers might not be as malevolent as she claims they are when something hits the side of the shuttle. I’m surprised; there did not seem to be asteroids in the immediate vicinity and the debris from the shuttle is caught high above the moon’s gravity field. Nothing should be falling from the sky.

The shuttle shakes again. I look to Shelly who is already staring up at the ceiling. Her eyes are calm. These are not the eyes of a woman who is insane, although she would have every right to be after what she’s been through this mission. “What is it?” I ask.

She doesn’t take her eyes off the ceiling. “I told you they’d come.”

+

The Flippers, as it turns out, are as malevolent as Shelly claims. They latch onto the shuttle and begin trying to pierce the hull. Neither of us has much time to investigate or strike back. I slide under the mainframe on my back, just in front of the pilot’s chair, and begin hijacking the secondary power system. Nobody has ever flown a shuttle on this kind of energy source, but then again, no one has ever been to this moon. No one has ever survived a trip to Saturn, and even if Shelly and I make it out, I will be the only person alive who’s made the trip alone.

My fingers run over multi-colored chords and beams. It’s so much more jumbled than I remember the practice mainframes being in school. Those were unused – all clean and easy to grasp. These are slightly damp. It’s hard to adjust them without my fingers slipping.

“You can reroute it by changing the emergency –”

“I don’t need you to talk me through it,” I snap. “Take the pilot’s chair.”

She sits down, her legs swinging in next to me. The last time we were together, this is where Shelly and I failed. We faced a problem – her being a high-ranking officer under great public scrutiny and me being a nobody, rumored to be a suck up, an average girl who needed to marry up to do anything meaningful with herself – and it broke us apart.

That last night, squared off in her kitchen with the lights on low, I told her it had never been her ranking that drew me. You were at the beginning when I fell for you, I said.

What about my potential? she asked.

What about mine? I asked.

“If we’re going to try, we need to try now,” Shelly says. “They’re through the first layer of the hull.”

“One second.”

She lets out a sigh. My fingers roll over the wires, plucking them free of their casings so I can sew them together. It’s simple machinery, really. All the fancy power sources, and possibilities all boil down to wire and casings, like the muscle and bone in all our bodies. I twist one of the wires into another. Sparks burn my thumb.

“Start on low,” I tell her.

She jams the shuttle into low, not gracefully. It shutters forward, unstable. “We need more power if we’re going to get into orbit.”

“Just fly,” I tell her.

I slide out from underneath the mainframe and hurry to the emergency power source, which sits at the back of the shuttle. We’re wobbling in the air now, hardly able to get even a few meters off the planet’s surface.

I yank open the metal casing to the iridium generator. Inside, iridium dust sits in a maze of metal tubing. It’s faintly luminescent – a startling silver – and stinks of something sour. Iridium dust is tricky. It’s highly flammable and even with all the safety precautions, one wrong move would explode the entire shuttle.

“Quickly,” Shelly says.

“Could you maybe hold her steady?”

The main power connector must be attached to the receptor at the bottom of the generator. The clip is small and slippery, like everything else. It’s my hands; I’m sweating like crazy. The temperature inside the shuttle has gone up by at least ten degrees, maybe due to the things still hacking away at the top of the hull. I wipe my hands on my uniform, then pick up the clip again. We’re really bumping along now. Shelly is an awful driver. She’s confident; I’ll give her that, but there is almost no way I can attach this during a bump and not blow us both up.

I exhale. Grab the clip firmly between three fingers. There’s a flow to a shuttle, the way it moves and ebbs. At the Academy, I learned how to predict when my pilot was going to bank hard, when we were about to hit a drop in gravity. I position the clip near the connector and wait. We hit a bump. Immediately after, I shove the clip on.

Sparks burn my fingers, but when I let go, the iridium dust illuminates. “The throttle,” I call to Shelly.

She hits it so hard I fall forward onto my hands and knees.

+

Nobody can hear a scream in the vacuum of space, but I can hear Shelly all the time now. I can hear her muttering through nightmares of losing her crew, stirring coffee with a small tin teaspoon, breathing hard as she runs on the holo-treadmill, the R-16 hurtling us forward, back to Earth and solid ground. Space: painfully large and painfully beautiful now that she is here with me.

Roz tells us we have only ten days left until we reach Earth. She sits in front of the camera, her black hair wild and curly, green eyes flickering. “Pretty soon, you’ll get to see Mars again,” she says. Next to me, Shelly crunches on her favorite pea salad, ripe with beets, freeze dried edamame, and dehydrated cheese. She wears an old Academy uniform, one of my extras, and it bunches around her waist and ankles, the blue bringing out the sparkle in her skin, which is much improved now. “How are you feeling about the return?”

“I could do with a pizza,” I say.

Shelly side eyes me, a smear of salad dressing on her upper lip. In the last week, I’ve noticed her looking at me like she used to look at me before everything went sideways. She brews coffee for me in the mornings, sets up holo-screens in the mess flashing pictures of the Grand Canyon and Mount Denali. “What does Houston think about all this?” she asks Roz.

“Houston is pleased with your survival.” She leans closer to the camera. “Houston will be providing you with a generous payout for your trouble.”

“I want dibs on the next mission out,” Shelly says immediately. “Doll and I both. She should be getting a promotion, too.”

Roz says that can be arranged. When we end the transmission, Shelly’s salad is gone, and in its place, there is only the smell of faint Cesar dressing, the tang of pepper and dehydrated lemon.

Behind us, under lock and key, an immobilized Flipper rests in the medical quarantine. It is a slim creature, narrow, and almost invisible to the eye, not unlike a ghost shrimp, something that is there one second and gone as soon as the light changes. I told her we needed to leave it, that dragging this thing back to Earth with us, when it killed people, could start something we don’t want to start. She asked what I was afraid of. It’ll put you in the history books.

I’ll be in them regardless, I replied.

The shuttle jolts, then evens out. “What shall we do with the time?” Shelly asks. “Plan your promotion ceremony?”

I look out the viewing window. Jupiter is long gone. In just thirty hours, Mars will fill our screens again, fiery and dangerous. Part of me wants to abandon the Flipper there, to see it expelled into the vacuum, writhing and scared and alone. But too, part of me is so much like Shelly. We fight, then talk about marriage. We deny our affection, then fall into bed like animals, clawing at one another. We are the type of women who see peril and move towards it. It’s what made me love her all those years ago. It is what will end up killing us both someday.

“Doll?” she asks.

“Tell me again how my messages kept you going?” I lean into her, placing a kiss on her cheek, and her lips pull back in a grin.

About the Creator

Chelsea Catherine

Chelsea Catherine is a nonbinary lesbian residing in St. Petersburg. They have two fun gay books available here: chelseacatherinewriter.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.