Some of the most well-known masterpieces of Classical literature were written by Augustan love poets. The Roman poets pioneered the genre recognized today as elegy, inspired by their Greek forefathers. Roman elegy became synonymous with first-person poems detailing the love affairs of male poets who had devoted themselves to a mistress, often with disastrous results. These intimate stories of deeply personal events offer unique insights into the ancient Roman world of sex and relationships. The poet Publius Ovidius Naso, better known now as Ovid, was one of the most original and accomplished of all the elegists of ancient Rome.

Life and Love Poetry in Ancient Rome by Ovid

Ovid was born in 43 BCE to a wealthy equestrian family in northern Italy, under the name Publius Ovidius Naso. After completing his education in Rome and Greece, Ovid followed the traditional path into a senatorial career in his early adulthood. After holding a few modest administrative roles, he quickly abandoned politics and devoted the rest of his life to producing poetry.

Ovid was already giving public readings of his poems in his early twenties, and by his mid-forties, he was the leading poet in ancient Rome. Emperor Augustus, on the other hand, sent him into exile in 8 CE, an event that dominated the rest of his life. The precise grounds for his banishment are unknown. They are described by Ovid as "carmen et error," or "a poem and a blunder." The poem is thought to be Ars Amatoria, which is erotically focused, although little is known about the error. Scholars say the monarch was directly enraged by some form of indiscretion.

Ovid's biography is more documented than that of almost any other Roman poet. Tristia, his autobiographical exile poetry, are largely responsible for this. The events of his life and the poems he wrote were inextricably linked, and the evolution of his poetic style mirrored the trajectory of his life. His earlier love poetry, which we'll be looking at, is lighthearted, funny, and occasionally satirical. Later works, like as the epic Metamorphoses and the mournful Tristia, however, take on broader, often more serious themes that mirror his personal struggles.

The Amores: A Touch of Personality

The Amores, which literally means 'Loves,' were Ovid's first published poems. The poems were originally published in five books , but were later reduced down to the three books we have today. The Amores describe the poet's feelings about love and sex while in a relationship, but the exact nature of the connection is never revealed.

Ovid describes a sensual scenario of afternoon sex in an early poem, 1.5. The window shutters are half-closed, and the light in the room is diffused, like a sunset or a beam of light shining through a tree. Ovid keeps it lighthearted by referring to his sweetheart as a "Eastern queen" at first and then as a "top-line city call-girl" later. The poem provides a vignette of a profoundly personal experience, leaving the reader feeling like a voyeur peering through the keyhole. He immediately tells us to fill in the remainder of the facts for ourselves at the conclusion, ostensibly to protect the moment's privacy.

When we are shown a picture of his lover's betrayal in poem 2.5, the tone shifts dramatically. Ovid sees her kissing another man in a public area and expresses his displeasure with her infidelity. However, as the poem goes, he admits that he is more irritated by the fact that she did not make a concerted effort to conceal her indiscretion. When he confronts her, she uses kisses of her own to win him over. However, the poem's concluding lines allude to his lingering uneasiness and jealously; was she the same with the other man, or did she save her best for him?

What percentage of what Ovid tells us is true? The ancient Roman love elegists frequently concealed behind the mask of a character, which was supposed to offer them creative freedom. However, they have the ability to make us feel as if we are seeing true human emotional events.

When alluding to his mistress, Ovid employs the pseudonym "Corinna" throughout the Amores. So, who exactly was Corinna? According to some experts, she was his first wife (Green, 1982). The fact that Corinna appears to be available to Ovid at all hours of the day lends credence to this theory. They are present at morning (poem 1.13), siesta (poem 1.5), chariot races (poem 3.2), and the theater (poem 3.2). (poem 2.7). Corinna was not a paid sex worker or a casual lover, according to this evidence.

Ovid characterizes his first wife as "nec digna nec utilis" (meaning "neither worthy nor useful") in Tristia 4.10, written 40 years later. We also discover that the first marriage only lasted a few months. Perhaps it was because of this intense early experience that the tone of the love poetry that followed changed.

Ars Amatoria: Lovers' Advice

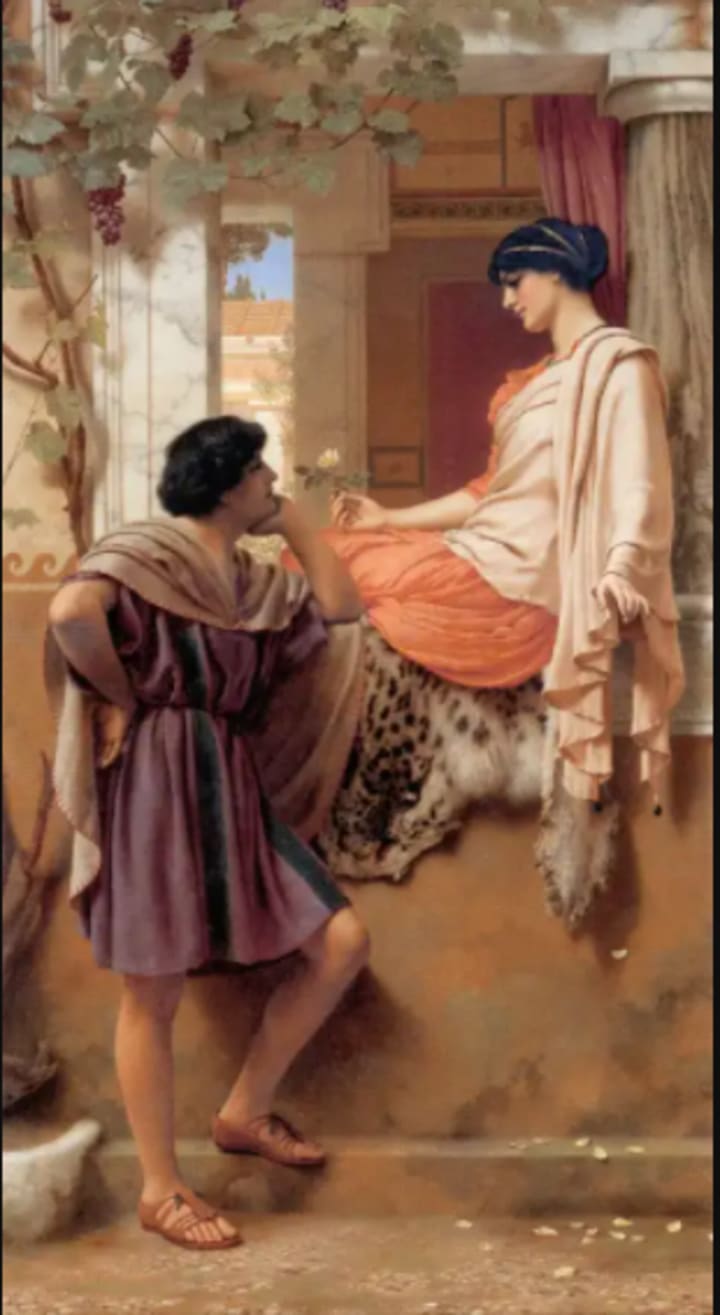

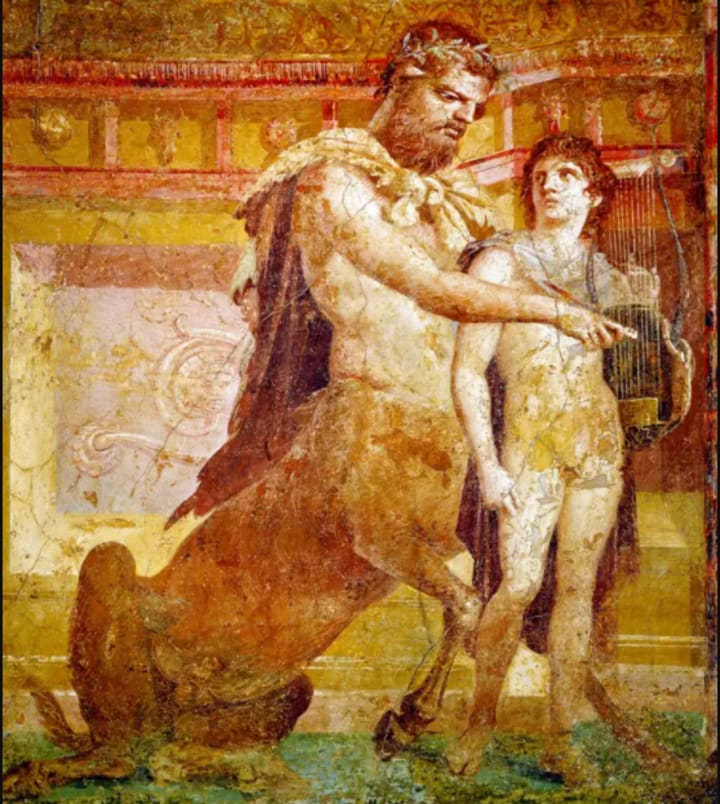

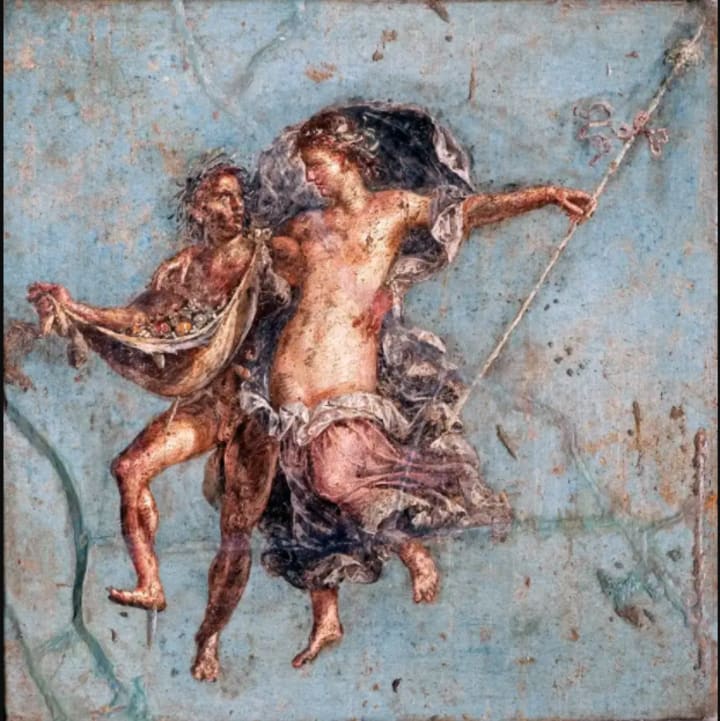

The Ars Amatoria is a compilation of poems written for those in search of love. Because the Ars is primarily concerned with the technique of seduction rather than the act of falling in love, we meet a more jaded Ovid here. Ovid is now a mature adult who has established himself as a leading literary figure in Rome. He also seems to have a lot of faith in his abilities to give dating advice to people who aren't as experienced as he is. He introduces himself in poem 1 with the phrase "like Chiron taught Achilles, I am Love's preceptor" (Ars Amatoria 1.17).

Ovid begins by recommending locations in ancient Rome where the most gorgeous women could be found. Shady colonnades, shrines and temples, the theater, the Circus Maximus, banquets, and even Diana's woods sanctuary beyond the city are among his favorites.

One of Ovid's best dating advice is to get to know the lady's maid, since she can be really helpful in the early stages of a relationship. He suggests that the maid be "corrupted with promises" in exchange for letting her mistress know when she is in a good mood. However, he warns against seducing the maid herself, as this could lead to complications later on.

Women are meant to be the target audience for Book 3 of the Ars Amatoria. As the poem develops, it becomes evident that the counsel given to women is focused on how to satisfy men rather than on how to please themselves.

Ovid recommends ladies to conceal cosmetics and make-up containers in order to keep the appearance of natural beauty. On the other hand, he emphasizes the need of putting time and care into their appearance, particularly their haircuts. He advises them to learn to sing or play an instrument because music is enticing and accomplishments appeal to men. He also advises ladies to avoid men who spend too much time worrying about their appearance. These guys are more prone to be interested in other guys and waste their time.

The Ars Amatoria bear a striking resemblance to the writings of Jane Austen, an 18th-century British author. Ovid, like Austen, gives much of his "dating advise" with his tongue firmly in his cheek.

Remedia Amoris: Love's Cure

The antithesis of the Ars Amatoria is the Remedia Amoris, composed around 2 CE. Ovid offers tips on how to deal with love breakups and broken hearts in this single poem. He asserts himself as an authority in this sector once more. Medicine is a key element in the poem, and Ovid is portrayed as a doctor.

"Eliminate leisure, and Cupid's bow is shattered," Ovid advises when dealing with a painful romantic break-up (Remedia Amoris 139). He recommends that one way to keep occupied is to go into agriculture or gardening and enjoy the results of your labor later. He also suggests taking a vacation because the change of scenery would help to distract the heart from its sadness.

Ovid also offers some tips on how to end a relationship. He is a firm believer in taking a harsh stance and feels that it is best to say as little as possible and not to let tears soften one's determination.

The Remedia Amoris is written in a mock-solemn tone for the most part. By citing Greek mythology in his courting advise, Ovid mocks the traditional vocabulary of rhetoric and epic poetry. He warns, for example, that people who cannot cope with a breakup may end up like Dido, who committed herself, or Medea, who murdered her children in jealous retaliation. Such extreme instances are intended to stand in stark contrast to the poem's background and to demonstrate Ovid's own literary abilities.

Ovid the Beauty Guru's Medicamina Faciei Femineae

The last chapter of Ovid's "advice poetry," often known as didactic poetry, has an interesting little poem titled "Cosmetics for the Female Face." Only 100 lines of the poem have survived, and it is assumed to predate the Ars Amatoria. Ovid is mocking more formal educational texts like Hesiod's Works and Days and Virgil's agricultural manual the Georgics in this passage.

Ovid declares in the Medicamina that it is critical for women to cultivate their attractiveness. While strong character and etiquette are more vital, one's physical beauty should not be overlooked. He also believes that women care more about their beauty for their own enjoyment than for the pleasure of others.

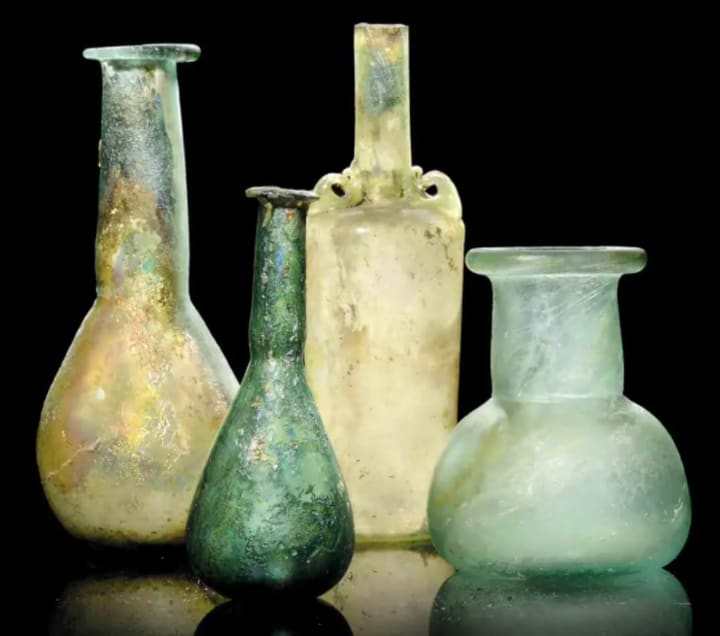

Ovid recommends several fascinating elements for excellent face masks based on the existing lines. Myrrh, honey, fennel, dried rose-leaves, salt, frankincense, and barley-water are all combined into a paste in one such recipe. Another involves a kingfisher's nest that has been crushed with Attic honey and incense.

In the poem, Ovid goes into considerable depth about how to use successful cosmetic treatments and make-up. His understanding of this subject is impressive and rare, putting him on par with ancient naturalists like Pliny the Elder. As a result, the Medicamina offers fascinating insight into the ingredients used in ancient Roman beauty preparations. It also complements the Ars Amatoria in terms of counsel geared exclusively at women on how to attract the ideal man.

Ancient Rome, Ovid, and Love

In his love poetry, Ovid's attitude toward sex and relationships can be regarded as careless and even dismissive. Clearly, seduction and the excitement of the chase are more appealing to him than the act of falling in love. The poems, on the other hand, contain a lot of humor as well as nuggets of excellent wisdom and exceptional literary flair.

Ovid's love poetry was revolutionary at the time. At the turn of the first century CE, his fame skyrocketed, and many members of ancient Rome's aristocratic society would have been familiar with his works. His poetry, on the other hand, was an outright rejection of Augustan moral and political values. Unfortunately, Emperor Augustus found Ovid's avant-garde approach to elegy to be too much for him. It cost him his job and, eventually, his life, as he died in exile in an imperial outpost distant from the city he adored.

About the Creator

Rashel

Rashel is an investigative journalist for Time, The Atlantic and other magazines.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.