To The Lives I Couldn’t Change

When Traveling Through Time, You Can't Change Anything.

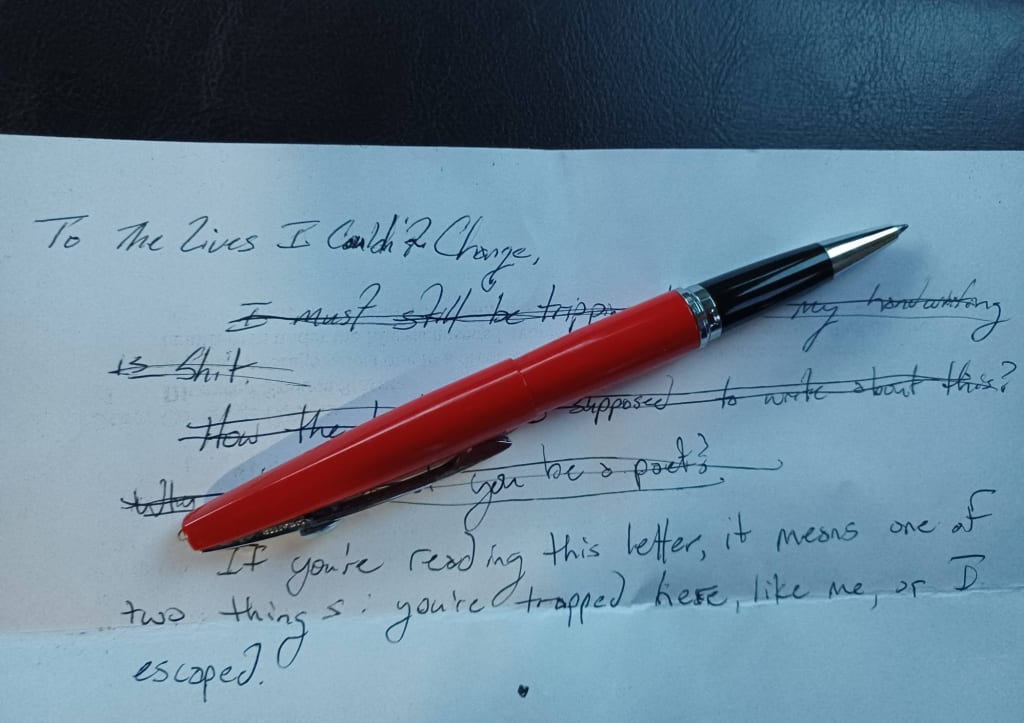

To The Lives I Couldn’t Change,

I must still be tripping; my handwriting is for shit.

How the hell am I supposed to write about this? Why couldn't one of you be a poet?

If you’re reading this letter, it means one of two things: you’re trapped here, like me, or I escaped.

* * * *

I know I shouldn’t feel guilt responsibility for your death; it was inevitable. You weren’t the first I visited or spoke to, but you’re the only one I tried to save. You didn’t dismiss me, probably because you’re as impulsive as I am.

You finish your daily run through the forest behind your house in Tennessee when I appear. It’s Wednesday evening, April 14th, 1999 to be exact. It’s not that date for me, not really; I’m experiencing time differently.

When I arrive, your life downloads into me—not just the feelings; the knowledge, too. For example, “download” wasn’t even a word I knew until this happened, or “Internet,” for that matter. And now I even know things about the future! Like, somewhere around seventy years from now—your now—people can attach a person’s scent to themselves and when that part of the body is sniffed, the smell becomes a hallucination.

Sorry, this is about you.

You don’t give a fuck about anything except whatever makes you stronger and smarter, so you run and read every day. You push yourself because your dad checked out on your eighteenth birthday. He’d wanted a son, but he got a daughter instead. He left the dog and the keys to the house, and all the bills that came with both. You’re thrust into adulthood the summer of high school graduation, but you make it… well, another twelve years, anyway.

You have lovers by the plenty, adventures, and friends. Real ones, not like the losers I hang out with, except Ashley. She’s pretty rad.

It was an accident. Everything is set, and choice is an illusion. It is the law of the universe. I’m definitely still high. Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Thanks, Newton, you dweeb. Though, I don’t think he meant this. He was twenty-three, in the late sixteen-hundreds when he named gravity so I don’t think he knew that when someone peers through the fabric of existence, parts of themselves become cancerous—not death cancer, but the mind mutates. Though maybe he did. Maybe he was a time traveler, too. Also, I know about Newton now, because one of you did. The old guy, I think. Sorry, I’m distracted.

You take the same drugs I took when I was fifteen—which I still am, but I feel over three hundred. So yea, fifteen is when it starts for me, and twenty-nine is when it ends for you.

You’re cooling down from the run when you see me, “Hey, are you lost?”

I look freakishly out of place, and my one-piece bathing suit and swimming trunks are providing zero warmth. I shiver while studying your face. You look like the picture from the cabin, except you’re still alive.

“What’s your name?”

I pause, “Matilda.”

“Where did you come from?”

“I’m, uh, I’m from 1985.”

You laugh, “You must be high.”

“Technically.”

You put your jacket over me; it smells of sweat. “Let’s get you somewhere warm.”

I stiffen and start to talk—fast. I tell you about the massive barn owl. The eerie cabin. The old lady on the porch. The storm. The woman in the car accident. All in extreme detail; and you listen, while I tremble, my feet in flip-flops.

You stare at me, which makes me uncomfortable; it’s like you’re dissecting my soul. “What did you take?”

I pull the plastic bag from the pocket of my swim trunks.

You snatch it from my hand faster than I can close my fist around it, “Why is the bag wet?”

“I jumped into the gorge.”

You open it; the drugs are dry, “Is that what I think it is?”

“Probably.”

“I’ve always wanted to try these… who knows, maybe you really are from 1985.” You pop some in your mouth.

My eyes widen—I was wrong, you’re more impulsive than me.

It wasn’t the drugs that did you in because they didn’t even have time to hit your system. You have an undiagnosed heart defect, and this was always going to be your last run.

You’re twenty-nine when you die; maybe that’s why I tried to save you because it didn’t seem fair you were going out so young, but it’s more that I’m selfish; I didn’t want to be alone with what I know.

My hands push between your breasts, a futile rhythm to get your heart beating again. I know it was going to end this way, but I still try, with hot tears on my face, my hands beating feverously.

Man, did I try.

* * * *

After the third death—the one I tried to save, but couldn’t, I accepted each reality is set—each end is inescapable, so I only watched this time.

I feel a bizarre melancholy on how you meet your end, and a sense of empathy for you in general which sits uncomfortably in my gut because, well, I don’t like you.

You take your gun everywhere. To the grocery store, family vacations, even across state lines where it’s illegal. Gun laws only apply to people who don’t look like you.

You play the hero image in your head every time you go to the shooting range. The phrase, “Just protecting my country,” plays like an echo, a background noise, an apparition whispering from this thing that claims so much of your attention. Because a mind is constantly aware of a gun. Where it is. If it's loaded. If it's secure.

You sleep with it under your pillow and glitch out on a conversation when your arm grazes its holster on your body. Moments of peace are pushed down by imagined threats. Emotional space and mental power are traded for this thing that proves useless in the end.

Though the danger did come, it didn’t matter, because you’re broken.

In high school, your genetics can’t provide the height and muscle the other boys have. All the protein and exercise couldn’t change it.

The bullies push and punch and yell “Queer!”

And you are gay; a scrawny gay kid in North Carolina in the mid-80s, with no resources or ways to find out that being gay is normal—so self-hatred and repression consume you.

At twenty, you marry a kind woman with simple features. Within the first five years, she gives birth to three daughters. During the fourth pregnancy, she has to have a cesarean. After they slice her open and pull your son from her womb, you ask the doctor to tie her tubes and he does.

At twenty-eight, you hold your newborn son, and for the first time, but not the last, you threaten, “Don’t grow up to be a faggot.”

When your father kills himself on your thirtieth birthday, the gun he uses to take his life moves into your house. You fire it every weekend at the shooting range and never think about how he used it in the end.

Fast forward to your today, the Fourth of July, 2026, it’s a month before your fifty-seventh birthday. Your family is here in the park, except for your son, of course, because he hasn’t spoken to you in years. He left at eighteen and he never came back. He’s now the same age you were when he was born. Your wife keeps in touch with him and passes along watered-down updates, but the image of him being a screwup doesn’t waver.

Your mind is on him, and your gun—the rest of you is unable to concentrate on the celebration, the endless bowls of food, the husbands of your daughters, your grandchildren.

A loud pop erupts, and your hand jerks to your weapon.

Scanning the area, you see me. My hair is too short for your liking, and you brush me off as one of those weird kids that calls themselves non-binary. Our eyes lock, and I know you recognize me because everyone else has.

The oldest grandkid pulls your attention back to the party, “Calm down gramps. It’s kids playing with fireworks.” She stares at your hand still on the sidearm. “Why do you wear that thing anyway?”

“To protect you.”

The grandkid rambles off statistics about gun violence, and you glaze over. The sun is so hot you’re sweating—each summer has been more brutal than the last.

Suddenly, there’s a ringing in your ear drowning out the world. You stand up from the picnic table, but a sharp pain in your right shoulder stuns you. You put a hand on your chest, and when you pull it back, it’s covered with blood. Your legs give out and you fall. There’s a cacophony of screams and gunshots.

Seconds move like years, until you see him standing over you, the sun directly behind this tall, white, man. He moves his head to block the light, and his face comes into focus.

At first, it’s relief, then his eyes are replaced with the muzzle of his gun pointed at you.

“Son,” you cough up blood, “Don’t—”

“Faggot.”

I watch you die, knowing your life, knowing your hate, knowing I can’t stop it, because I can’t change any of it, and I cry.

* * * *

It’s Valentine’s Day, 2007. You kicked out your leech of a now ex-boyfriend the day before and decided it’s time to paint the living room. The color doesn’t make sense—a smoke-stained eggshell white—so you leave to get supplies. The snow tires on the car are bald and there’s a blizzard coming. You’re drunk, and angry, because when aren’t you?

You’re thirty-seven and have been drinking since you were fourteen. You get your alcoholism and rage from your father, both of which have hardened your feminine features over the decades. Today, your version of today, a half-a-bottle of red wine in lieu of lunch doesn’t phase you.

Your mind circles around the breakup and pinpoints every wrong word your ex-boyfriend said. Every dish he never cleaned. Every time he didn’t make the effort to go down on you. He was useless, and still, you stayed with him for over four years, because you can’t be alone. It’s why you work long hours. It’s why you bought a house three times too big for yourself, so you can always host parties—intricate get-togethers, mostly with co-workers, and occasionally a friend from town. You’d cook all day and create meticulous playlists. You know how to work a party and get people to flow in the way you want.

Too bad relationships aren’t like this. This last boyfriend, the leech, he played you. He would have kept it up for years more had you not found his sketchpad under his side of the bed. The illustrations aren’t F.B.I. worthy. You aren’t even sure if it’s illegal. They’re drawings of kids. But they’re doing things. Horrifying images you can never erase.

When he returns, his clothes are waiting for him outside in the snow. The pictures he’d created are torn into pieces scattered amongst the pile. You’ve changed the locks, and don’t answer when he beats on the door, but don’t hide that you see him either. You stare at him through the window, one arm at your chest, another gripping the neck of a bottle of wine. No need for a glass. You sip and watch him lose his shit.

He cries. He begs. He comes up with excuses—all lies. He calls you a crazy drunk, among other names, then tosses his clothes into the car, the car you paid for, and leaves.

Pieces of his drawings soak in the snow, and you collect and burn them.

You call into work, lay on the couch by the woodstove, stare at the flames, and wonder why you were with him so long. He’s hairy and sweats through the sheets. He did this thing when he had anxiety attacks where he’d bite the knuckles of his pinkies until they bled. But he was cute enough and mostly good in bed. Yet in the end, he’s broken. You were talking about having kids, too. You laugh at this thought as you fall asleep, eyes dry, and heart empty.

At the hardware store, one of a chain of eight in the state of Vermont, the one you’re a CFO at, the employees greet you but don’t ask questions. You’ve got the familiar “piss off, keep walking” energy about you.

It’s snowing now.

I’m at the front door, holding every memory of you in the forefront of my mind, like a movie I’d watched, every detail and smell and sensation as fresh as if it’d happened to me. I see you at the checkout line and I’m staring, awkwardly. I must look like a lunatic, and then I sound like one.

“I need to talk to you,” but the wine on your breath tells me you won’t listen. “I’m from the future. I mean, the past.” I shake my head, “It doesn’t matter. I need to talk to you.” You push past me, but I stay by your side. You threaten to spray me with mace, then hurriedly get in the car, slam the door shut, and drive away. I follow. Not in a car, or on foot. I appear at the end when your vehicle is off the road.

The snow is up to my calves, and my feet are going numb because I’m wearing flip-flops.

You look at me, and I smile because there’s something in your eyes. Something I’d seen at my last stop, the one with the old woman on the porch, with the mezcal, weed, and ominous final words, “You can’t change it. It only changes you.” The old woman had that same look. I’d soon know this is the expression you all have in those final moments.

You return a half-smile, “I know you,” and I say it back, and you die.

* * * *

On March 9th, 2045, the world governments declare yet another pandemic. It’s the fifth one since 2020. Maybe the eighth. You’ve lost count. The climate is shifting—the five months of winter in New Hampshire are down to two.

It wasn’t the new virus that got you, it was the spider. It might not have killed you if you had gotten treatment, but nurses and beds are few and far between. You sit with your pain in the crowded emergency room until you can’t anymore. Being a lifelong pacifist, it came naturally to put others first, so you tell yourself someone else needs the bed more than a frail old man.

A man who went to protests instead of the military, and never married or fathered children. Who has friends around the world. From travel and rallies. You go to the peace gathering after 9/11. You’re at Occupy Wall Street. Standing Rock. You march with BLM and the LGBTQ community whenever you can. You were there handing out food during the nationwide workers' strike. You took part in the Uprising twelve years ago, and the next one seven years later. At every natural disaster that needed aid, you went; and there were plenty the last two decades.

You go where you think you are needed, and at seventy-five, you leave to make space for someone else.

At home, you read a book until your arm gives out from the pain. The venom is doing its job. Your body is failing. I move from the kitchen to you, and when I touch your shoulder, you give me that same look of recognition. Then, you’re gone.

* * * *

This is as far into the future as I make it: Wednesday, August 4th, 2060

You might have been my favorite, not that I should have favorites. That’s like having a favorite child. Not that I have kids. I’m fifteen. If you hadn’t been the first, I would have let the madness take me. Maybe it’s that I needed your words, whether they were relevant or not, to get me through. Because even if what you said wasn’t about what was happening to me, my mind made it mean something. Maybe it’s because I’m high, but more likely it’s that I need it to make sense.

It’s your birthday. You’re ninety-one.

You’re not surprised to see me walking up to the cabin in flip-flops, boy’s swimming trunks over a girl’s one-piece bathing suit, a pixie cut, and too many single stud earrings; and I recognize you from the hologram in the cabin, but my mind is still in pieces. So I concentrate on the rocking chair that’s hovering, legless, over the porch. I stand at the edge of the house, a bewildered look etched into every molecule of my face.

Then I watch you do that thing, where you hallucinate people because their scents are implanted in your body. The back of your hand is up to your nose, the middle and ring finger rest under each nostril. You breathe deep and smack your lips together. “This is my old lover. Oh, she was a wild one!” You raise your left forearm to your face, take another deep breath, your eyes roll back in your head a moment, and you cry, “That one was my ma. She died when I was born.”

“Mine too.” The words feel empty in my mouth.

“You look scared. Don’t be. Death comes for us all.” You gesture at the bottle beside your rocking chair. “I’ve been saving this mezcal. It’ll take the edge off.”

“This is the drugs, right? It’s cause I took that, whatever that was, that Carey gave me. That bitch, she—”

You raise your hand, a calm and authoritative look in your eyes, and I immediately go silent. You take a hit off a joint, offer it to me, but I ignore it and sit down. I run my fingers over the wood, which doesn’t feel right.

“There hasn’t been any lumber in over a decade. This is all manufactured something-or-other the scientists made up.” You take a swig from the bottle, “Who knew it’d be the end of us.”

“What would?”

You take a hit off the joint. “Greed. The planet could only produce so much, and we took it all. Selfish pricks that we are. And now it’s over.”

“Over?”

“Don’t you worry, you’re not alone now.” You tilt your head down, breathe in the space between your breasts, and your shoulders do a short dance.

“Who was that?”

“My kid. They died, about twenty years ago, during one of the Uprisings.”

I eye the bottle, then turn back to you, “What is going on?”

“It’s the end. It’s been coming a long time now.”

The air pressure dramatically shifts, and I turn to the horizon. In the distance is a massive storm. I run towards it, then turn to see if there’s an escape behind the house. The death storm is everywhere, and closing in fast.

I look to you, and your hand reaches toward me. I run back, my flip-flops making a strange, clacking sound on the barren dirt. I take your hand and lock eyes with you. The storm is nearly on us, and you smile, unafraid.

“You can’t change it. It only changes you.”

* * * *

I’m writing this to you even though you’re me because I’m not the same person anymore. That doesn’t make sense. Nothing in this stupid letter matters.

This is when time became intermingled, on a Tuesday in the dead center of May of 1985. It’s a clear, cloudless day. You want to leave Oklahoma, but you never will. You’re a few months shy of sixteen.

You’re with weird friends, day drinking by the gorge because it’s better than being alone. It’s an act that’s free and untamed like you want to be. You’re all skipping school because they teach nonsense; though you don’t have the dedication to check the lies, you know it’s all bullshit. The same way people who are brainwashed know they’re brainwashed. The way people who are gaslit know they’re being gaslit.

That’ll be a fun word—gaslighting—to introduce to the group, assuming I make it back.

You’re anarchists—sort of. You’re teenagers. You don’t like authority, so you steal alcohol. You skip school and sneak out when you’re grounded. Fuck the police, and the parents, and the teachers, especially the pervs.

You’re making out with Ashley when Carey walks over.

“Break it up lesbos. I got some killer shit right here.”

“What is it?” You ask, your mouth still wet from Ashley’s tongue. She isn’t your girlfriend, because that isn’t a thing girls did in your town, but man, do you love her.

“It’s righteous, that’s what.” Carey’s grin is that of a hyena.

You stand, take the little plastic bag, open it, pop some drugs in your mouth, gesture them at Ashley, who declines, then tightly roll the remainder back into the plastic bag, and stuff it into your pocket. “The rest of the gang is gonna wanna try these,” and you jump over the edge of the gorge, like an imbecile. Like you believe you’re invincible. Like nothing matters.

Maybe you were still high from the endorphins from making out with Ashley because you’ve lept off this cliff before, but this time, you get the jump wrong.

You hear stifled voices pushing through the abyss, “Matilda! Oh, fuck, Matilda!”

* * * *

I don’t know how to describe this next part other than It’s a void without time. There’s nothing, then, I smell static; it smells like it would taste if I licked a television. Then, there’s suddenly a world, and I’m on a path. The snaps of the brown leaves blanketing the beaten-down earth give off a dull defeat as their spines and veins crunch beneath my flip-flops. The trees are massive and reach into the sky beyond the clouds. They’re strange colors, like when the contrast on a show is turned way up or way down. Everything feels off.

Six feet in front of me is a barn owl. It’s cartoonishly large, and its eyes are missing. I know now that this creature is Death; it smells of sulfur and the burnt wick of a candle. It looks at me, uninterested, a piece of meat drips from its beak. I pass close enough to hear the owl’s feathers ruffle.

There’s a cabin. Then it’s gone. Then it’s back again. I have an overwhelming desire to get away from this gargantuan owl of death, even though I’m not afraid of it. I step through the door that’s a black rectangle of swirling inky colors, like a thin layer of oil seeping up from hot pavement. The walls flicker in and out of existence like I’m blinking my eyes, but only the cabin disappears and reappears.

It’s the drugs, I tell myself. But I know this isn’t true.

I’m inside, then I’m out like the world is hiccuping. I’m staring at the owl, its back is to me. It turns its head a hundred and eighty degrees, two black holes where its eyes should be, its beak still filled with something dead. It drops its meal, then I swear, it speaks to me—into me.

“You can’t change it. It only changes you.”

“What the fuck—” I’m in the cabin again, looking at a table. There are six pictures. One is a polaroid, the image is blank like it’d just been taken. Two others are framed. Three are holograms—I know what holograms are because Ashley made me watch Star Wars.

Crap, Ashley! She’s going to be so pissed. For a moment I forget where I am.

Then I glance back at the pictures. In every one is the face of someone dead.

I close my eyes, and I’m in the woods again. The static is stronger. Then I spaz out, or the world does, or whatever, and it’s overpowering. I’m running, and then I’m on the ground. Then I’m running. Then I’m curled up in a ball, in a sea of leaves that make no sound, my body writhing with the information flooding into me. The rivulet of a day is folding in on itself, its structure collapsing and expanding. I can hear the universe; it has a heartbeat.

It’s all happening at once, and I start to go insane, “I don’t want this!”

Then I see you, the You that is the old woman on the porch. Your features are ancient. Your face is one I know. It’s one of the holograms on the table in the cabin.

Then it’s the You who worked and drank too much.

Followed by the You who pushed yourself until your heart gave out.

The You who hated yourself.

The You who lives to help, and dies to give space.

Then the You that’s me but isn’t me. Naive and defiant. Impulsive and fearless. You’re floating at the top of the water of the gorge, facedown, blood swirling everywhere. I close my eyes, but it doesn’t matter, because the vision is in me. The side of my face is broken, and I’m dead. I’m dead. I’m dead. It’s the drugs. It’s only the drugs. I’m high. But I’m still dead.

And every other death, all of You, You’re all dead too, and I scream. Mouth open, vocal cords silent. I cry without tears. I weep without sound.

* * * *

This goes on for an eternity and without time at all.

After I see You all, feel Your lives, I’m back here, in this cabin. In a world that’s not real. Everything is gone. The forest. The owl. The door. Only the polaroid remains, still blank. I imagine it would be my lifeless body floating in the gorge if it ever develops.

I’m in this stupid cabin that’s four walls and a roof. A pen and a notepad appeared, so I wrote all this down, because what else am I supposed to be doing? What should I be doing in a world that isn’t a world in a cabin lost to time? So I write about all the things I’ve seen. All the lives I have floating around in my head. All their your our deaths.

Because I think I get it now. I don’t think we all end up here—this has to be a fluke—but like, when I died at fifteen, if I hadn’t, you know, woken up in this nightmare, in a nightmare, that is in a nightmare, I would have woken up in the woman who’s a runner and died from heart failure, erasing my life from before. Then into the woman who worked too much. To the man who hated himself, and passed his hatred onto his son. To the man who was an activist, who never saw his self worth. To the woman on the porch, with the mezcal and weed, hallucinating the past, waiting for the world to end.

We were all born on the same day, August 4th, 1969. All with fathers who weren’t there, and mothers who died giving birth to us. All living different lives, and all afraid to be alone.

Maybe it’s the same reality, and this consciousness, or soul, or whatever, split when we were born, but it’s still connected. Maybe it’s multiple universes. Regardless, these lives, as different as they seem, are all heading to that same end, with people trying and failing to stop the inevitable storm that kills us all.

I don’t know what to do with this. What does it matter if we all die but don’t, yet humanity dies in the end because of our greed? Our selfishness? That it doesn’t matter how kind or angry or focused on work or ourselves or others; in the end, we still die. We try to control the earth, and instead it destroys us.

All this knowledge and I’m here, by myself, scared out of my fucking mind, trying to piece together all this heavy existential junk of why I can’t change any of it. Why couldn’t one of you be a philosopher? Or a scientist?

And now you’re all dead and it’s only me in my fifteen-year-old body and three hundred years of all our lives swirling around my drug-addled brain. I am so broken and tired and have never felt more alone.

* * * *

I don’t know how long it’s been. Time doesn’t mean anything anymore.

But what I did figure out is to hell with this bullshit.

Fuck what the owl of death said—that I can’t change it, that it changes me. What kind of cult defeatist nonsense is that? I didn’t know jack shit before, and now—now I have all of you, all your lives and knowledge, and I’m going to use it to find my way back.

I’m going to change everything.

About the Creator

Melissa Shekinah

Melissa Shekinah has been traveling for three years. She's visited all fifty states, parts of Canada, and Mexico. In the first two years of travel, she received a MFA in Creative Writing and completed her second novel of a trilogy.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.