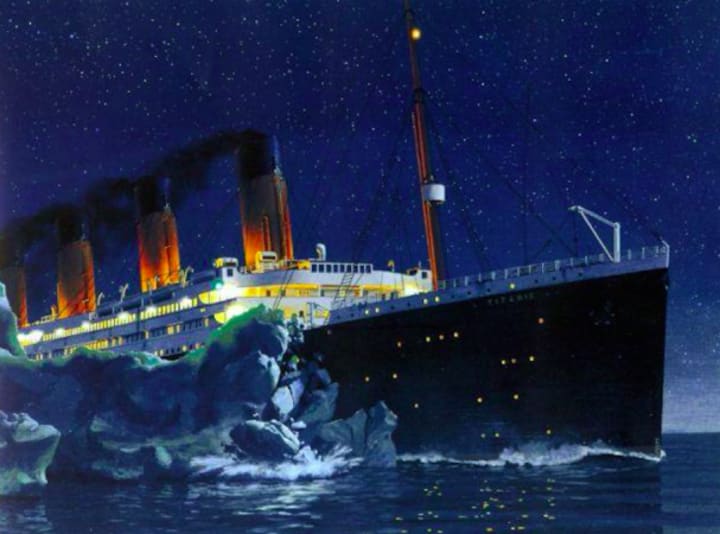

The Ship of Dreams: Chapter 8

Iceberg Dead Ahead

Space-time is that one grand variable and constituent that connects all things, living and otherwise. Through its shapeless form, infinite roads and pathways transmit incalculable bits of information and data via this elaborate connection that is the very matter of life. It is this medium that communicates the happenings of the world, almost instantaneously, at a rate that is faster than even quantum physics would seemingly permit for in the exchange between particles.

A sudden drop in temperature relays to the Titanic’s crew and its passengers that they have entered freezing waters and that by virtue, there may be formations of ice lurking out of sight in the great watery abyss in front of them. Almost in the same way that very intricate pathways of fungi burrowed underground communicate the information between plants that an animal is approaching an area to graze on its contents. Or the way, that in our current epoch of human civilization, the Internet of Things relays details and instructions amongst all connected computers in the matter of a billionth of a second. In this way, literally, everything is information to be consumed via the conduct of the five senses in what was referred to in ancient years as the great chain of being that linked everything known to man.

Thus, it made sense that what would serve as the ship’s communications center would be located at the forefront of the Titanic’s vast D deck. Positioned parallel to the beginning of the grand staircase and with it, the first-class entrance, the operating room that was the Marconi Suite had the perfect vantage space to oversee all the ship’s affairs. At the very least, those affairs were most important.

This area of the ship consisted of three conjoined rooms that were quite small. There was the operator room itself consisted of the operator station equipped with its state-of-the-art telegraphy machine which was placed neatly on the wall adjacent to the worktable provided for the operators to conduct their work.

Adjacent to the operator's working space was their sleeping quarters where a single bed and wash area were located. The thought with its design was that only one operator would occupy this space as they oscillated between shifts and their differing shift change. This, of course, was to ensure that someone was always attending to this vital aspect of the ship’s overall functionality.

Sitting to the right of the operators living quarters was what was referred to as the ship’s silent room. In this area was located Titanic’s main communications transmitter. It also led its way to an area that held many of the more important parts of an electric switch that controlled Titanic’s wireless set, and with it, the switch that was meant for the ship’s emergency broadcast. In this way, the Marconi Suite acted as the ears and voice of Titanic.

Like always, the droning hums, beeps, chirps, and buzzes could be heard propagating out and issuing forth from its innermost chambers. Even the silence between the devices tapping documented and told the story of everything taking place aboard the ship. Some of these were the stuff of secret affairs that were meant to be handled with discretion, while others still instructed colleagues to have their private railroad cars at the ready by the time the Titanic arrived in New York.

Manning the station did not work for the faint of heart. It was a tumultuous ordeal that consisted of ever switching between listening to the chatter received from all other parties to that of hurriedly tapping the appropriate message in response. There were few seconds in-between that allowed for the organization of these messages so that their contents were distributed where they needed to go.

It was here that twenty-fiver-year-old Jack Phillips sat at his post, meticulously laboring away like a possessed madman. His left hand pressed the operator's earpiece that hung loosely skewed atop his finely groomed head the closer to his earlobe. As he interpreted its cryptic messages, his other hand was burdened with the task of having to alternate between writing down these communications and tapping away at the ship’s wireless telegraph machine.

During the time that would prove to be the eleventh hour of Titanic’s doomed voyage, young Phillips was busy working Cape Race. Cape Race was the name of the wireless station located in Cape Race, Canada, and it was a job that entailed seeing to the correspondence to and from the ship’s passengers. This was an additional responsibility that had to be done on top of his more usual duties, and with the ship nearing the end of its trip, there was an even greater influx of these messages that night. Even for someone with the experience of Phillips, who had spent the last several years working for the Marconi Company, it was no easy task. The most challenging aspect was the way that the new technologies meant that all the passenger’s letters were transmitted on the same frequency that all ships conducted their communications.

In this onslaught of information Phillips picked up on a unique dispatch that was more urgent in its tone at 10:00 P.M. that night. The message in question that Phillips gave a keen ear to was from the nearby ship, The Mesaba. With his hand at the ready, he jotted down the corresponding dots and dashes relayed to him through the wireless communicator. Upon his interpretation, the message from them that he wrote down on the memo pad read: Titanic — heavy pack ice and a great number of large icebergs.

Annoyed, the arrogant prodigal youth rolled his eyes and shoved the document off to the side of his workspace. He then furiously tapped out; I am busy before setting back to his work. To his count, he had passed six reports down to the captain regarding ice warnings that day, and he was certain that he was aware of the fact. He was certain because of his knowledge that Captain Smith had already taken to altering Titanic’s course on one such occasion, and as such, Phillip was sure that Captain Smith would not want to be bothered by any more of their likes.

This was the main theme for Phillips over the course of the hour while his assistant Harold Bride climbed in his nighttime attire and got ready for bed as most of Titanic’s passengers took to at this time. As the hour neared its conclusion, he received another document of this similitude. This time the message radioed in came from a Californian. The contents said, “Say, old man, we are stopped and surrounded by ice.” In his growing irritation, Phillip furiously tapped away Titanic’s infamous last posting to Californian before it meant disaster as he replied with, “Shut up! Shut up! I am busy. I am working Cape Race.”

Up in the Captain’s Bridge which tragically never received these final warnings, the word being conveyed there was of a slightly different nature, and yet, remarkably it was still very much the same. Here First Officer Murdoch strolled across the room and checked its temperature gauge as he adjusted the collar of his jacket more firmly against the nape of his neck.

“There’s been a significant drop in temperature sir. By a good four degrees I would reckon sir,” he reported with a backward glance at Captain Smith. “That and the water is as dead a clam as they come. I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a flat calm,” he continued on as he made his way back through the boxed-in room.

“To right you are,” Captain Smith answered, his eyes gazed and fixated themselves out towards the expanse of the horizon. “Like a millpond, there’s not a breath of wind,” he trailed off more like he was talking to himself than anyone else in the room. He wore a grave expression on his face as a cautionary man might wear if he heard a sudden noise in the middle of an otherwise silent night, or as one who was contemplating whether he had forgotten some important detail.

“Yes, it’s a damn shame too sir. There’s no doubt it will make seeing icebergs more difficult to see, what with there being no break at their base,” he let out, reading his body language and sensing the Captain’s worries as if he were reading his mind.

“On that note, I believe I’d best be off. There are other pressing matters that I must attend to,” Captain Smith retorted with a little nod as if he were agreeing that the thought was best.

“As do I. It’s long overdue that I should relieve Lightoller of his post,” First Officer Murdoch said as the two men faced each other as in they had both reached some unspoken agreement.

With that, William Murdoch stomped his feet in place as he gave the Captain a little salute before making his way past the numerous engine-order telegraphs and the great big helm of the navigation section of the bridge as he let himself out of the room.

Once outside, Murdoch rounded the corner and made his way along the ship’s deck. He immediately felt the sudden drop in temperature and the way that the heavy wind brushed against him as he walked the length of the ship. Murdoch groaned to himself. There was nothing that he hated so much as the cold, and it was so freezing out that it made a man’s limbs ache. His thoughts wandered off to all the things that would be required of him over the course of the shift out in this open space, and he had a strong feeling that it was going to be a long night.

Still, he wasted no time in his brisk stroll down the length of the ship. In fact, it encouraged him to think of the way that it created heat for himself the faster that he went. As this thought passed, he blew deeply in his hands and found himself somewhat dispirited to see the thick fog that was his breath. He shook his head, disappointed in himself, mostly because he found himself thinking that he should know better as to the way that the more that one focuses on how cold they are, the colder they become.

Half an hour had passed since Titanic sent its cold reply to the ice warnings and all the Titanic staff was going about this routine shift. It was Titanic’s lookouts, all six in total, that were under the most rigorous shift changes as a result of the cool and harsh weather conditions. Due to the freezing temperatures, those on deck had changes placed on their routines and schedules which called for a constant rotation of two hours shifts. So, it was conducted in perfect harmony that while First Officer Murdoch went to relieve Lightoller that both Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee climbed the large main mast of the ship to begin their post on Titanic’s birds' crows’ nest.

His numb fingers grasping around themselves as he climbed up the pole, Fleet chanced a cautious glance down at the deck below. It took all his strength to suppress a deep gulp of anxiety as he considered the one hundred feet that he hung from and that separated him from the ground below. Even so, a sudden sense of pride welled up in the bosom of his heart. Fleet was generally employed as deck boy and able seaman, and as such, was not used to the heights that the lookouts were subjected to. Not only that but he had a tremendous fear of heights, so it made him feel extremely proud of himself, not only for overcoming his anxieties but also account of how well he had done so far in putting up a kind of front that they did not even bother him in the slightest. In that moment, he found himself contemplating whether courage was not necessarily the absence of one’s fear, but rather, their ability to rise above it and live with it. The only thing that Fleet knew for sure was that living with feelings of angst was worth the increase in his paycheck.

“You know, they usually recommend not to look down when someone is climbing something,” the older Lee said as he finally clambered his way into the crows’ nest with a slight smile to himself that could not be seen by Fleet.

“How’d you know? You weren’t even looking,” Fleet let out in a dumbfound state of astonishment, his hanging and gaping jaw matching the tone in his voice.

“Well Fleet, it’s pretty obvious when you stop and think about it for a moment. There you were climbing, and suddenly there came a pause in your movements. So, you either slipped some and had to readjust yourself, fell, or stopped to look somewhere. Seeing as to how I heard neither scream, thud, movement, nor anything to suggest the first two options, then it must be none other than you stopped to look at something. And I don’t strike you as the sentimental type to stop and gaze off at the beauty of the stars in the distant horizon, so one can only assume that it was a downwards glance,” Lee answered as he stood himself up in the nest, watching as Fleet made his way in as well.

“Then I suppose you’ve made a fool out of me. That’s a hell of a point, and I can hardly argue with that logic,” Fleet said with a goodhearted laugh, feeling pleased that he could joke with himself. The words had hardly parted his lips when he took a grasp of Lee's large meaty hands that helped pull him up to his feet inside of the nest.

“Ah, come now, don’t be too hard on yourself. Think nothing of it. Anyways, have you seen the binoculars? I can’t see a damn thing. The night is as black as Ismay’s soul, or at the very least as Titanic is,” Lee inquired, feeling around in the dark as he did so like a blind man looking for a lost object.

“Haven’t you heard by now? There is no getting to them at any rate. They are on board but won’t be accessible anytime soon. The rumor now is that the key to the safe isn’t even on the ship. The last bloke that had him was that David Blair chap and the thought amongst the crew is that he pocketed it and forgot to leave it behind as he was assigned to another ship. Damn shame too. This is hardly the night to be on the lookout relying on nothing but eyesight alone,” Fleet answered, the thick cloud that was his breath in the freezing temperature barely visible unto them both.

“I did in fact hear something to that extent. I had only thought or hoped that they had turned up somewhere or that someone had found them by now, and that the rumors were nothing but mere speculation, but I suppose it was nothing more than a wish,” Lee said as the two men turned to the forefront of the nest that faced the bow and the ocean in front of them.

“Wait a sec,” uttered Fleet under his breath such that it sounded as if sec was pronounced with the letter t. His face was scrunched in on itself as if he was having a hard time processing or comprehending something.

“What’s that Fleet,” Lee returned in a tone of voice that was as weary as the grave expression on his face. “Well?”

“Speaking of stars, something doesn’t seem right don’t you think? Don’t you notice it as well? I’m not quite sure I can say exactly what it is, but something seems a little off,” Fleet replied, still speaking as if he were trying to solve a difficult puzzle or advanced math problem.

“What on earth are you going on about Fleet? Where’s that you’re looking at? I don’t see a thing,” Lee cried out, his frustration acting to mask how scared he found himself suddenly becoming.

“That’s exactly my point, Lee. There is just a little way ahead. There’s nothing there, or rather something missing. I believe it’s the stars. They are scattered everywhere, all around us. But not there, not in that space just ahead. It’s just sheer darkness. What do you suppose could blot out the stars like that,” Fleet asked pointing out in front of him as the two men leaned over the sides, squinting their eyes the better to make out what Fleet was trying to make out?

“I mean it’s hard to tell in conditions such as these. Maybe it’s just a patch where there are fewer stars. In other circumstances, it would be easier to tell. There is the possibility that there is an object…”

“Iceberg,” both men exclaimed at that moment as Lee trailed off midsentence. Without so much as a second thought, Fleet immediately turned right round, grasping at the rope to the bell placed on the nest and gave several hearty tugs, ringing the bell three times to indicate what danger lay ahead as he shouted out for all to hear at the top of his lungs, “Iceberg dead ahead!”

It was 11:39 p.m. when Officers Fleet and Lee sounded the alarm as to what lie ahead. In the advent of the early 1900s, modern science burgeoned the thought that all the world operated in terms of microscopic wavelengths operating on all levels of existence. This came in the form of the discovery of the cathode ray, or that of the electron and proton. In the same year, scientists introduced the quantum realm in advance of Planck’s Constant.

To this end all the world and its elements communicated to the Titanic the perils that lie ahead. The particles, or lack thereof, in the crisp air-breathing down the nape of the passengers’ necks, combined with the freezing waters below had signaled that this would be their fate. In did so in the constant fluctuations and oscillations of the radio frequencies aboard, but to no avail in what was the most disastrous instance of miscommunication and lack of foresight.

That doomed great colossal ship was bearing a remarkable twenty-four knots when the alarm was sounded; a curious choice gave the conditions that they were subjected to. It created the greatest dilemma of First Officer Murdock’s entire nautical career. In less than a second, he had to process that he had to make a life-or-death eleventh-hour decision about how to steer the massive ship around the icy rock in front of them.

What would ensue would become a topic of great scrutiny and controversy in the years ahead. In short, the criticism hints that the young Officer acted in due negligence entering his four-hour shift that fatal night. It may even suggest the reason why Murdock had been demoted from Chief to First Officer.

Nevertheless, in hearing the distress call sound, the eager Murdock made his way over to the then nearly frozen railing in order to get an estimate of what to do. Much to his dismay, he observed the great black haze that lay directly ahead.

There has been great speculation as to whether or not this was the way that it happened. In stark juxtaposition, stories have reported that the First Officer gave his order without the iceberg even in his direct line of sight. Both scenarios considered, it took William Murdock thirty seconds to make the calculations he felt necessary to maneuver around the bulky obstacle ahead, bellowing out for all to hear, “Hard-a-starboard”

Murdock’s decision was based on the hope that he could avoid either side-skirting the iceberg or a head-on-collision by steering away from the danger ahead. In part, the thirty-second or so reasoning came from a similar experience that he had at sea which he had navigated rather successfully. Nevertheless, this has been widely viewed as one of the greatest mistakes in maritime history, with experts asserting that this is the exact recipe for a collision. That being said, it is a common misconception that the engines were also reversed. What was seen in the Titanic’s three-engine design was that the center engine was not reversible, and thus this was not possible.

It would seem that consciousness to acts as a wavelength. In rapid succession, the remaining officers on the bridge in full awareness used all their state-of-the-art apparatuses to send the message to the reciprocating engine room of the order at hand. Simultaneously, the Officer’s of Titanic turned her wheel as far to the left while the firemen in the reciprocating engine room below stoked the fire to give the ship the necessary energy needed to perform such a taxing task on the ship. As they did so, the signal was given to shut the heavy watertight compartments that could be found in the Titanic’s large hull and underside.

In less than thirty seconds, the Titanic has sailed some four miles through the ice-infested waters. All the Officers and passengers alike watched in great anticipation as the obstruction neared ever closer to the ship. Titanic veered gently away from the massive bulk, like some object in space trying to escape the event horizon of a black hole. For a brief moment, it seemed that Murdock had made the right call and that the crisis had been averted. Murdock could be seen muttering, “Come on, come on, over and over to himself, as he prayed, somewhat to himself that they would miss the berg.

All of a sudden, a splintering crunch pierced out throughout the night skies. It was then, 11:40 p.m. and a great rumbling could be felt all throughout the ship. To put the instantaneous effect of it all into perspective, Quarter Master Bob Hitchens felt the steering mechanism quiver and shake vehemently in his hands as he manned the wheel.

The unsinkable ship of dreams had met her match. Measuring in at 882 feet from tip to tip, the iceberg ripped a gaping hole of about two hundred feet into her hull, with the causality of tearing the bulkheads in the location out of place in a zipper like fashion; two-hundred feet being the estimated size of the berg in question.

It was then that the firemen quickly learned their true social status aboard the ship as the sirens to the watertight compartments wailed as the water came gushing in at the precise time that these hatchways ground shut. Only a handful would manage to escape as they slowly churned shut at this time.

In totality, it was as if the ship had encountered an unexpected earthquake at sea. The only evidence otherwise was the great chunks of ice that littered the deck, which the passengers happily kicked around, and the solid mass distancing itself from the ship with each passing moment. In observation of the event, all of Titanic’s Officers stood frozen in place in complete awe, as if they had just experienced the impossible. Titanic had just struck ice, and now all they could do was wait and see what the damage was.

About the Creator

Aaron M. Weis

Aaron M. Weis is an online journalist, web content writer, and avid blogger who specializes in spirituality, science, and technology.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.