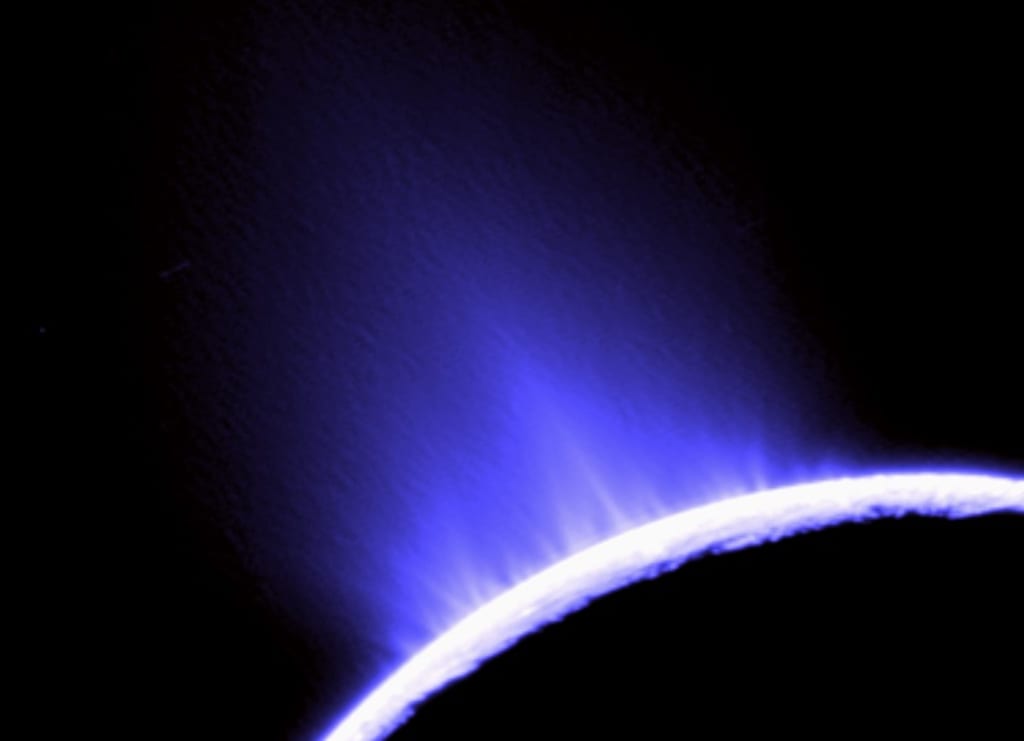

The Plumes of Enceladus

Deep within the cloudy mass of Saturn’s E ring is no place to discover your Ship Nav is failing.

Our earlier approach had been nothing short of awe-inspiring. As we flew towards the swirling grey globe of the gas giant and its colossal rings, ‘we’ being the ship and me, I just sat in the pilot seat and stared and stared and stared. I knew I would never see anything quite like this again. Closer-up, it was a different story. What had been a vast bright bow of blue, stretching off into distant space either side of the ship, now become a dense cloud of microscopic ice particles, more gray than blue. It felt like we were trapped in a giant, ghostly snowstorm.

“There’s absolutely nothing to worry about,” insisted Kulvinder from Mission Planning when we were running over the program back on Earth. “The biggest particles are no more than a few microns in diameter.”

I wasn’t convinced. Although the low relative velocity of the debris at this point in the mission meant that these tiny crystals were no threat to the ship, we would still need to maneuver around any larger particles encountered. Most of the ice crystals would simply bounce off the shielding, maybe all of them, but I wasn’t about to take any chances. Which is why I put my foot down when it came to navigation. The onboard IA had been trained for months with a data model that had taken the math genius of an entire university to construct.

A shudder inside the ship brought me back to the present.

“Report flight status!”

“Mission proceeding as planned. Single anomaly: retro burn delayed.” The Nav system voice response did not fill me with any confidence. The ship needed to reduce approach velocity to reach the right orbit before proceeding with the science mission. At the current angle of approach, we would be hitting the icy surface of the moon below in no time.

“Query retro burn delay?”

“No further data on burn delay.”

“What do you mean, no further data?”

“Repeat: no further data available. Will report further when data available.”

It was typical of Flight Nav to report in neutral tones an event that looked set to spell my imminent doom, along with several billion dollars-worth of space kit.

My primary mission was to collect samples from one of the icy plumes of Enceladus. I had been selected because of my Doctoral thesis which considered evidence of microbiological life in the vast ocean beneath the frozen crust of the Solar System’s second brightest object, the sixth largest moon of Saturn. Enceladus shared an orbital path with Saturn’s E ring, through which I could now see the dazzling surface of the moon, fast approaching. Too damn fast!

Saturn’s E ring had been produced from microscopic ice particles drawn up in spectacular plumes, generated from liquid water far beneath the frozen surface of the moon. The plumes had been discovered almost a century ago. It was my job to take a closer look but not as close as we were getting.

“Flight status update.”

“Fight status: risk of collision with object ahead high and increasing, Saturn moon Enceladus, distance six decimal two five times ten power three kilometers, relative speed …” so the report continued. It meant I had less than an hour before impact without the necessary thruster braking.

This was not how the mission had been planned. The ship was supposed to brake to a comparable velocity with the ring particles and Enceladus itself so that drones could be deployed to take samples of material directly from the cryovolcanic plumes.

I ordered a further status update. Silence. This was not good. We continued to accelerate towards our doom. Then, as the ship slid into the upper cone of the ice plume, so acceleration reduced. The velocity of the ship decreased, which should not have surprised me as much as it had. The upward thrust of the micro particles was pushing the ship back like an object captured in a waterspout. Without any intervention from Nav (by now completely silent) we had achieved a stable trajectory and began gently to ease into a lower flight over the icy moon.

Then we started to move again, this time in the direction of the source of the plume of ice, which must be reducing in force, no longer holding the ship up. We were falling but not accelerating, given the partial lift of the plume. Further and further the ship fell towards the surface of the moon but with no appreciable increase in rate of fall. It was as if the ice plume had caught us in its grasp and was lowering us down as gently as it could. Not that gently, though. The ship was rocking, spinning, shuddering but nevertheless falling in an almost controlled way.

The mission flight display indicated that we were barely a kilometer above the surface and so an impact was imminent. I tried to hail the voice control again without success. Switching to manual override, I was unable to engage the power system and the chances of me flying the ship by hand successfully were not good. I was by no means a pilot and the only craft I had flown in had been Nav controlled from take off to landing. I resigned myself to a total disintegration on impact but as we reached zero altitude the ship not only survived but plunged through what must have been a thin patch of ice crust into the ocean below.

Surrounded by darkness and with a faint shaft of sunlight penetrating through the thinner layer of ice above, we were now deep within the liquid ocean beneath the ice. Here we were, me and the ship, alone in the ice-covered ocean of Enceladus like some kind of submarine. I had no idea how the ship would behave under water.

I switched on the floodlights but there was little to see. Mostly dark, graying gloom with lots of particles suspended and moving through the turbulence created by the ship. My first thought was that the pressure cabin was designed to withstand pressure from within, not from outside. Fortunately, the craft began to rise again, its natural buoyancy taking over.

At this moment I thought I saw movement through the obs window. Straining my eyes, I could see something weave through the water. Probably just the liquid flowing outside, I told myself, but wait. I could see fins and what looked like a tail. The creature was enormous. As it approached, I could see a massive eye looking directly at me, like the eye beholding Ahab. I was face to face with a colossal underwater animal.

Forget the microbe detecting experiments, I had just made the historic first discovery of alien life in the Solar System. Not micro-organisms as expected, but a great big, gray, oversized whale-like creature.

“I come in peace from another world,” I said, for want of a better introduction. The great globe of an eye that peered at me through the observation window gave no indication that its owner had heard my pathetic comment. A leathery eyelid closed over it briefly, as if winking, and then continued to stare at me.

About the Creator

Raymond G. Taylor

Author based in Kent, England. A writer of fictional short stories in a wide range of genres, he has been a non-fiction writer since the 1980s. Non-fiction subjects include art, history, technology, business, law, and the human condition.

Comments (2)

Thanks Joseph, keep up the good work! Ray

Fun read, Raymond! Same subject, different approaches. Thanks for checking out my story as well, glad you enjoyed it.