The Chauffeur

a time traveler's memoir

June, 1914 – Bosnia:

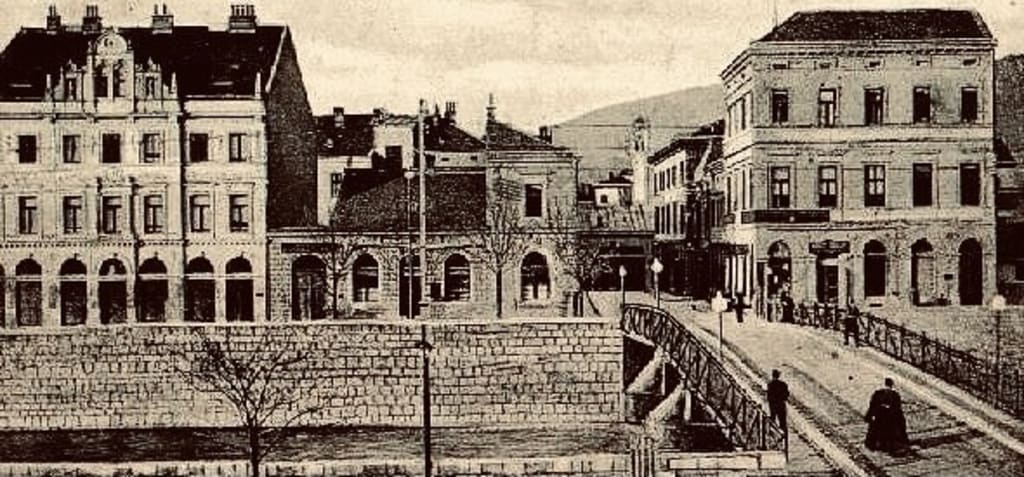

I knew June in Bosnia could be hot, especially if Spring has been particularly dry, a fact to which the greatly diminished depth of the Miljacka River which transected Sarajevo in a westerly direction now attested. On its own, it might have been tolerable, pleasant even, if I had been allowed the comfort of the customary summer wool haberdashery or the billowy linen garb of the local ceremonial tradition. But as it was, I had nearly sweated through the coat of my livery uniform by the time the Archduke reemerged from the Town Hall where he had delivered his prepared remarks to the assembled dignitaries of the city.

So far, everything about his visit had gone according to plan, including the errant grenade lob into the motorcade earlier this morning which had caused over a dozen collateral injuries and left one of our cars a mangled and smoking ruin in the middle of the street just past the Cumurija Bridge. Understandably, this had a dampening effect on the Archduke’s previously jovial spirits, and from the driver’s seat of my Gräf & Stift touring car, I watched as he moodily descended the steps of the Town Hall towards us in the idling motorcade below. He was accompanied by no less than a dozen other city officials and nobility of various distinction, all of whom were engaged in a dispute over what should be the next stop on their itinerary.

The Archduke was in no mood to be contradicted, and, in the end, with much blustery insistence, his opinion prevailed, --as I knew would happen, --and directions were given that we should retrace our steps along Appel Quay on route to the hospital to visit those injured by the morning’s bombing. The Mayor, wishing to maintain the good graces of his crown prince, conceded and even volunteered to lead the way.

I could feel my pulse quicken as the dignitaries climbed into the six car strong cavalcade, and with an impatient rap of his cane on the glass partition between us indicated that I should follow the rest post-haste. We set out along the street, flanked on either side by adoring crowds wishing to catch a glimpse of the esteemed visitor to their town.

All things considered, it made for a wonderful spectacle. It was everything that I had hoped it would be, --an impressively mustachioed man of stalwart Teutonic build arrayed in spotless military whites, resplendent with a full chest of ribbons and medals, nodding graciously to the people who politely waved their arms and cheered as he passed, while his wife did likewise while even lending the additional flourish of an occasional wave of the hand. I could not help but think they made an excellent pair, and like her husband, she cut an excellent figure with her broad and richly be-plumed hat and her much ruffled traveling ensemble, completed by high-waisted jacket and a parasol held aloft by hands clad in white satin gloves.

I could not help but feel an irresistible thrill at being fortunate enough to be a part of it, and yet I knew I could not let myself get carried away with the moment. I had a job to do that would, if we were lucky, change the course of history forever.

The perspiration on my forehead and hands intensified as we rode along, inching at a parade’s pace nearer and nearer to the critical juncture. We passed by a first bridge, then a second. The Latin Bridge was next and I could see it looming in the distance, then become larger and larger as we approached. Soon enough, it was upon us and, as anticipated, when the Mayor’s vehicle turned right, headed for Franz Josef St., the other car in front of me followed directly behind. My car was next in line, and now the definitive moment had arrived.

I signaled right, slowed, but then made my break for it. I jerked on the wheel, spinning it to the left, and gunned the engine. I could feel the gears begin to grind as it roared sluggishly in response, then shot across the bridge, narrowly missing one of the bystanders who had edged his way into the road in the hopes of getting a better view.

For a moment, I could hardly believe that I had done it, and suddenly I became aware of myself laughing uncontrollably like an idiot in disbelief as we arrived safely on the other side of the bridge, overcome as I was by an overwhelming sense of giddy triumph knowing the crisis that I had just averted. The Archduke, however, did not appear to share in my amusement and was instead beside himself with fury, railing at me vociferously to turn the car around immediately while once again banging his cane on the glass partition in an effort to get my attention.

But that was out of the question. I had come too far to jeopardize the mission now, and all at once, I saw the near whole decade I had spent preparing and, in an act defying the once secure laws of physics, traveled back in time to achieve it flash through my mind.

--------------------------------------

October, 2022 – My Apartment:

It all began on a Tuesday evening much like any other, and, as was typically the case, I was running late to the bi-weekly meeting of the historical society I had started while at university some years ago, --the For King and Country Club, or FKCC as we sometimes abbreviated it.

The nature and provenance of the society, as its name alluded to, was simple enough: I had always been fascinated with royalty. Not only the pomp and pageantry of it all, but also the singular expression of a people that it provokes. If times are good, that most exalted figurehead of state was rightly praised and revered by his adoring subjects, lauded by them as being God’s own anointed protectorate of their shared fate and who, in all humility, undertook this awesome duty with a sobering sense of majesty. If times were bad, however, history was replete with an abundance of evidence that there was never so ready a scapegoat as the sovereign onto which the shiftless and disgruntled rabble heaped their maddened grumblings, even to the point of being violently overthrown, --at the sharpened edge of Madame Guillotine’s angled salute to brotherhood, for example.

Believing that I was not particularly alone in this fascination, I had decided upon a whim of disenfranchised boredom to advertise for the fellowship of those similarly persuaded. I was hardly disappointed, and in short order there were a few of us who met regularly dedicated to the appreciation, --and at times study, --of the multitude of monarchies of history, although Europe admittedly consumed the majority of our attention. This was hardly a surprise to myself, as history shows a plenitude of examples of the recurrent appeal of monarchy, with even the great democratic revolutions of the Enlightenment giving way in short order to some of the most incorrigible strong men of history, --from Bonaparte to Stalin, it must be admitted they ascended their exalted throne by, at least in part, riding the crested wave of popular sentiment in the wake of plebeian descent into emancipated aimlessness and societal decay.

Over the years, we had remained a small society, and in that time I found that our number tended to stabilize around a somewhat arbitrary half-dozen or so members, not the least of which was because whenever some newer members decided out of an inexplicable curiosity to join our ranks, it was inevitable that some other member would depart our company citing philosophical differences.

As one may readily guess, achieving consensus opinion was near impossible in our society, apart from our steadfast and most essentially unifying belief that monarchy was never so intrinsically evil as it was regularly perceived, and that perhaps it would be better if it made a comeback in contemporary politics.

This proposal, whenever it was raised, was invariably the cause of much debate in our little society and embroiled us for several months in disputes over the nature of or limits to the perfected form of monarchic rule. Some advocated for the unrestricted autocracy of a righteous philosopher king, others were more measured is their approach favoring a more vestigial figurehead and leaving the run of common affairs to other forms of government, while still others lauded every other intermediary configuration in an attempt to broker some kind of compromised reconciliation of the more fanatical parties.

I myself was a staunch proponent of the somewhat controversial position that most contemporary bureaucracies represented something more or less akin to “non-hereditary monarchies” in which the incorporeal structure of the state had, in some abstracted sense, assumed to itself pride of place in the minds and hearts of the citizenry which monarchy had once more overtly enjoyed.

It was not uncommon for these debates to become rather furious and culminate, albeit seldom, with the ignominious effrontery of a glove slap most commonly associated with a dueler’s quarrel. Still, for the greater part, these disputes unraveled themselves without consequence, comfortable as we were in the mutually understood acceptance that the influence of this society of ours was entirely inconsequential beyond its most immediate constituents.

Most recently, however, with the death and much anticipated funeral of Queen Elizabeth, we found ourselves enjoying an uncommon sentimental unity, each of us believing that this event represented nothing less than a somewhat tragic changing of the guard, the end of an era, the like of which would, in all probability, never be seen again. That had been a particularly melancholic time for us, and had necessitated the calling of an additional meeting of our society to plan a watch party for the funeral.

We had all agreed to call in sick for work that day, --or at least those of us with regular employment, --and the whole experience was complimented with a near inexhaustible supply of tea and sandwiches made especially for the occasion. It was imperative that, out of respect for the departed, anything we made was among the Queen’s favorites during her life, or at least there could be no evidence that her palate was particularly opposed to it. We made a day of it, and by the end none of us could claim not to have dabbed away a tear or two.

Little did I know, however, that such a unity was not to last much longer, and as I dashed up the steps to my apartment, found the rest of the members huddled restlessly around my locked door, either smoking their pipes or checking their watches in irritation. They were all there, save one who had admitted he had some prior and unavoidable obligation. But his absence was countered most conspicuously by the presence of a gangly newcomer. He was unlike the rest of us, not only in age, --for he was demonstrably older, --but also appearance. While we, for the most part, constituted and motley crew of rogues and urban vagabonds, --regardless of how much I tried to impress upon them the importance of the society’s dress code, --this stranger obviously hailed from a more established professorial career. More than the others, he appeared particularly annoyed at my tardiness, and the severity of his expression underwent little to no variation, apart from the ever so subtle curl of his lip as it clenched around the butt of his cigarette and then relaxed to allow a billowing exhale of smoke to escape his mouth.

“Nice going, being late to your own meeting, you goof,” one of the members chided as I rattled my key around in the finicky lock until it clicked. Then, with a grinding creak and a gentle bump of my shoulder to release it from its frame, I opened the door.

“Where were you?” another inquired as we all shuffled inside. “Chatting up that chick at the bodega again? Come on, man, it’s just getting sad at this point. You have to know she’s not interested in you by now.”

“We don’t call those bodegas here,” I said, embarrassed not only by the accusation itself but also because I could tell our newest member was less than impressed at the quality of our membership and I felt an obligation to put our best foot forward in his presence. While the rest were either getting themselves situated around the table or plundering my refrigerator for a cold beer, I pulled aside my closest friend, Alan, who not coincidentally was the only other founding member still remaining.

“Who’s the new guy?” I asked, casting an askance look towards where he stood quietly against the wall with his arms folded. But Alan only shrugged and shook his head.

“Just brilliant,” I thought to myself, “a whole evening wasted on introductions and useless bickering rather than discussing more important matters, --like whether we were content to give Charles an honest run before wishing he would kick the proverbial bucket and yield the throne to William and Kate.” At least that’s what I wanted to say.

“Good evening, and welcome, all of you, to tonight’s congress of the For King and Country Club,” I began instead, wishing to affect as best I could a decorum worthy of our raison d’être. “Since we have a new member with us tonight, why don’t we all go around the room and introduce ourselves, --maybe your name, how long you’ve been a member, and your favorite monarch of history. Be as creative as you like and points for the most obscure!”

“Don’t bother,” the stranger interjected brusquely, his voice apparently even more egregiously effected by his cigarette habit than his teeth. “I’ll introduce myself, --hello, I’m Dr. Novák, a professor of physics and an inventor of sorts, I found you lot by happy accident, and I’m looking for a volunteer, --alright, now that’s out of the way, let’s get started.”

The rest of us, taken aback by his tour de force, could only look about the room and then confusedly at each other, until finally their attention settled expectantly upon me as if I were supposed to have some idea what this was all about.

“Get, um… started with what?” I asked hesitantly. “And what does this have to do with monarchy?” Dr. Novák appeared amused by my incredulity.

“It has everything to do with it. I see you like to talk about it, but I’m giving one of you a chance to actually do something about it and restore it to its rightful glory!”

“I told you I’m an inventor,” he continued more matter-of-factly in response to our palpable stupefaction and blank stares. “Well, I invented a time machine, --I think.”

“What do you mean I think?” I asked bluntly.

“I mean I don’t have a cat anymore, but I’m ninety-two percent certain the year 1800 does.” More blank stares.

“Okay…” I observed fatuously, “but then what do you need any of us for?”

“I don’t fancy risking my own life over an eight percent uncertainty,” Dr. Novák replied frankly. “But from what I see in front of me, it’ll be one of you deadbeat’s only opportunity to do something meaningful with your life.”

“And what would that be?” my friend Alan retorted, taking umbrage with the term deadbeat.

“Why change the course of history, naturally!” beamed Dr. Novák, obviously thrilled at the possibility. “You’re all monarchists here, aren’t you?” We all nodded.

“And you wish to see it restored, yes?” Dr. Novák continued. More nods.

“Well then, there’s your answer. One of you will do it, I'm absolutely convinced. Now who'll it be?”

“But how does it work?” a pedantic nebbish of a man squeaked from the back of the room.

“Nevermind how it works. You wouldn’t understand even if I told you.”

“Does it hurt?”

“How in blazes should I know? The only one who could is my cat and he’s in 1800.”

“No, I think he meant how does it work as in what could we possibly change about history that would restore the monarchy,” I said, hoping the clarified question spared the now thoroughly subdued inquirer further humiliation.

“Well then he should have said that, but I’m glad you asked. That’s the spirit. It goes something like this,” Dr. Novák remarked, at which point he began to lay out his plan in excruciating detail.

By the time he had finished, several of the members had excused themselves for the evening and another few had fallen asleep, leaving only Alan and myself awake upon its conclusion.

“So, what do you think?” Dr. Novák asked pointedly. “Which of you will it be?”

I looked at Alan, then backed at the doctor, and contemplating the scathing veracity of his deadbeat accusation, nervously raised my hand.

“Good man. Meet me here tomorrow and we’ll begin your preparations,” the doctor replied handing me an address card.

--------------------------------------

August, 2024 – Dr. Novak’s Laboratory:

Over the next couple years, my appointments with Dr. Novák became increasingly frequent as my preparations for my mission intensified. My primary discipline was a rigorous study of history with particular attention given to the day of the assassination itself, but by no means limited to that event exclusively.

According to Novák, as he insisted I address him, it was essential that I be thoroughly prepared to understand the gordian knot of tribal relations dating back a near millennium to fully appreciate the situation I was about to get myself into. The Slavs, after all, are a complicated people, and even if no discernible difference is perceptible to any outsider, they all insist emphatically that they exist.

In addition, it was imperative that I become fluent in one of two languages--German and Czech--and at least passable in the other, and I spent many countless hours immersing myself in both.

Though perhaps most important of all, I was drilled endlessly by the doctor on the particulars of the mission and how he expected it to be successful, which was the nature of our appointment today.

“You’re late. Again,” Novák said in response to my ringing of his front doorbell. “I’m in the laboratory. I’ll buzz you in.”

His laboratory, --if it could be called that, --was really just the basement of his home, a sort of clammy dungeon of a place outfitted with a sort of study comprised of a desk which faced a whole bank of computer monitors and a host of maps, both contemporary and historical, hung on the opposite wall.

“Today, we're going to review the plan again. I need this stuff to be as native to your mind as remembering to breathe,” he said as I entered.

“I think it is,” I replied grumpily as I waited for my morning cup of coffee to kick in. “It’s the German that’s the problem.”

“I’m not worried about your German,” Novák answered flippantly. “If you’re speaking German, pretend you’re Czech. If you’re speaking Czech, pretend you’re German. You’re good enough with either to be believable. At least until you’re fluent in both. Now let’s get started. Who’s Leopold Lojka?”

“The chauffeur.”

“And what does his sister call him?”

“Poldy?”

“She doesn’t call him a question.”

“Poldy,” I reiterated with declarative emphasis.

“Very good. And where does he live?”

“Telč, in Czechia.”

“And how does he become the chauffeur?”

“He becomes a professional chauffeur in the employ of Count von Harrach. He only meets Ferdinand once… in Sarajevo.”

“And how will you ensure that it’s you instead of him?”

“I follow him. Do everything his does. Get to know his friends, or at least the ones who will be useful. And then… when the time is right, sabotage.”

“How?”

“He likes to drink.”

“Very good.”

We proceeded in this manner for another several hours, and sometimes I was obliged to give the answers to the same questions in either Czech or German, depending on what language the question was asked in. It was a tedious business, but I understood the necessity of it.

When at last we reached the end, Dr. Novák said, “Very well done. You’re just about ready. How much time will you need to say goodbye to everyone? Will a week be enough?”

I had to admit that it was. The only person I needed to say any farewells to was Alan, and he was already fully aware of the impending nature of this eventuality.

“Alright then, meet me here at our usual time in exactly one week. And don’t be late.”

--------------------------------------

September, 2024 – Dr. Novák’s Garage:

Next week seemed to arrive sooner than I had hoped, and while I still believed in the imperative nature of our mission, I felt a twinge in my gut knowing the risk of what I was about to do. It was presumed, by both Novák and myself, that the only chance of a return trip lay in the possibility that I was unsuccessful, but there were other things we were not as certain about, --like whether I would age the same or what it would feel like as I was being transported or even how long it would take. Novák’s professional opinion was that the only way time travel was possible was for someone to become something like abstracted from it, and then reinserted into time once the desired destination was identified.

For this reason, Novák insisted that it was essential that I have in my mind as vivid a sense and mental image of the town of Telč as possible, and that I be able to meditate upon it exclusively for extended periods of time without distraction.

“If you can imagine it, you can locate it,” had been his exact words on numerous occasions to me, as he distractedly tinkered with various calculations in his computer models.

Arriving at Novák’s residence, I found him waiting for me expectantly in what he called his foyer and smoking his customary American Spirits feverishly.

“Here, put this on,” he said, handing me a garment bag by its protruding hanger. “It has everything you need. You can use the lavatory there.”

I took it, and did as I was directed.

Inside, I found a plain suit with matching vest, a shirt and collar, a tie, a pair of ankle-height boots, and the necessary accessories, --socks, suspenders, and the like, --and in the beast pocket of the suit were the counterfeited krona and identification papers I had helped create for myself. I got dressed quickly, and presented myself for Novák’s final inspection.

After a thorough examination and confirming I had the money and identification, he nodded approvingly, and then took me to his garage. Inside was a thing, most closely resembling a hyperbaric chamber. It was plugged into the wall, and the monitor attached to it displayed the year 1904.

“Go on, in you go,” directed Novák with an alarming lack of either sentiment or ceremony, and then added a snappy “bon voyage” as he closed the lid.

I closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and tried to imagine the town square of Telč at night as vividly as I could. The machine whirred, and then my whole world went dark.

--------------------------------------

September, 1904 – Telč, Czechia:

Arriving in Telč felt like waking up from a dream, and as I blinked open my eyes, it was no wonder. To all appearances, I had passed out in a puddle in the middle of the town square in the dead of night. Novák was perhaps a madman, but he wasn’t insane. His machine had worked exactly as intended.

I got up, gathered myself, and went to the nearest inn I could find, resolving to begin undertaking Novák’s plan first thing in the morning.

Over the following years, Leopold Lojka had not proved himself difficult to find or predict, though it was interesting to discover that he only became a chauffeur as a last resort after his aspirations for a career in law had failed to materialize.

And as luck would have it, I found the Count von Harrach uniquely indiscriminate in his hiring practices. Both Lojka and myself were given employment, so now all that was left to do was ensure that I secured that most essential assignment, --and endure in the meantime the flighty and eccentric temperament of the Count, who, though he boasted of a most prestigious lineage, was someone I found to be hopelessly daft.

--------------------------------------

June, 1914 – Sarajevo, Bosnia:

The only regret over the course of the whole mission I could think of as I brought the throaty rumble of the Archduke’s car to a mumbling halt in front of the hospital, was that I earned Lojka countless reprimands from his employer by incessantly sabotaging his credibility, my pièce de résistance occurring the evening before our departure for Sarajevo by getting him blind drunk and arrested for creating a public disturbance at the local tavern, a feat which earned him a night’s sleep in the drunk tank of the local constabulary.

These memories were interrupted, however, once the car came to a stop and my royal passenger disembarked and savaged my face with a swift strike of his gloved hand.

It stung exceedingly, and I could feel my cheek flush and pulse from the blow. But remembering my training, I knew it was best to remain silent, making neither so much as any protest or apology. The less I said and did, the better.

“You blasted idiot!” he bellowed, his prodigious mustache quivering with pompous rage at my apparent impertinence. “What do you mean breaking with the motorcade like that! This whole visit has been one disaster after another! I’ll be a laughingstock! And as for you…” he fumed, furiously wagging a reprimanding finger in my face, “I see to it you never drive so much as an ox cart by the time I’m done with you! The Count will most certainly hear of this!”

He composed himself quickly, and after straightening the breast of his martial uniform with a vigorous tug, offered his hand to his lady wife to assist her from the vehicle with an air of exorbitant dignity and grace which seemed uncommonly natural to him. I had become somewhat used to being addressed in this manner, and found myself disappointed that my regard for him had waned so considerably over the few days I had been in his employ. I had expected him to be of a demanding temperament, and though for these past years I had prepared myself accordingly, I had thought he would have been of a milder disposition, something more compatible to that of his wife’s. I liked her, and though I could not boast any definitive opinion on her character, I thought she exuded the very meaning of the word nobility. She was gracious, free from the necessity of pretense, and though she comported herself with a kind of delicate charm suitable for her station, understood the limited expectations pertaining to it, and in response, gratefully regarded all others with the same good humor by which she had won the hand of her husband.

To my disappointment, however, she said nothing and simply followed her husband into the hospital to visit the victims of the bombing from earlier that morning, without so much as an acknowledgement of my existence. Part of me endeavored to give her the benefit of the doubt, a generous consideration that her nerves were still on edge from the events which had prefaced their visit to the hospital, and perhaps that was so. Still, I hoped that as a commoner herself she would have been more sensitive to someone such as myself in such a situation. It was difficult not to allow this to color my opinion of them and I could feel myself becoming disillusioned with the entire enterprise of monarchy at having made their acquaintance. I left my post to light a cigarette, wondering to myself whether I had indeed embarked the world on a far better trajectory.

The remainder of the imperial convoy rumbled into view and their retinues made a confusion of themselves wondering which should park where and who should follow whom into the hospital after the Archduke. I was reprimanded again by Mayor Curcic who had taken lead of the cavalcade from the town hall.

“How dare you get out of formation!” he thundered, horrified at the loss of decorum that had happened under his watch, something which he almost certainly feared would earn him the irrevocable displeasure of his sovereign and an eternity of embarrassment. “You’re lucky if I don’t prosecute you for kidnapping!”

Having felt that he had done his civic duty in administering this verbal chastisement, he too ascended the steps of the hospital to pay his respects to the injured, followed close behind by the other dignitaries in tow, in order of their original configuration.

In their irresolvable ignorance, I knew that it was impossible for them to fathom what had been done for them, and having nothing else but indignation at my supposed egregious impropriety, I understood now that, ungrateful as they were for the great service I had performed, my ignominious dismissal from their service was almost certainly guaranteed, or worse yet, --though perhaps just as likely, --they would determine to prosecute me for a minor act of treason. I was probably now a wanted man by some of the most powerful men in the world.

So, fearing for my life, I hastily discarded my uniform, and mingling as best I could with the gawking crowd which had followed them to the hospital, determined to travel to Munich and seek out a certain Austrian-born painter and do what I could to encourage him to not so easily abandon his dream of becoming an architect.

About the Creator

Sean Byers

Literary hobbyist who, in an act of sophomoric hubris, once dreamed of writing the great American novel. My ambitions having cooled since, I am now content to write for the pleasure of the craft and whoever finds my work of any interest.

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (1)

Interesting and well researched story! I read about the arch duke recently and wondered at the incident, how unlucky he was to end up crossing paths with the assassin again by chance. Definitely a Good case for the time travel competition! Good luck!