The birth of their daughter was the turning point in learning his wife’s mother tongue. Allan joked that it was because he didn’t want them to speak behind his back in front of him. Once, with Learning Portuguese for Dummies splayed across his chest, he worried his joke betrayed his motivation was not for his wife or his daughter.

He didn’t learn until they moved to Brazil to be close to her mom when the cancer came back. His wife became a nurse once more at the hospital in Maringa. In this city of trees, Allan was a stay-at-home dad and got a kick out of walking through the dense park, with its Japanese architecture hidden like trinkets. They had a life of their own in his mind, prompting him to make up little narratives—his favorite, an emperor’s soul trapped inside a fat tiger figurine. And when his daughter slept, he pitched into the family income with the lifeless writing of translations, mostly sales collateral and business briefs, from Portuguese to English.

Still, expressions of language eluded him. Saudades was the famous example. No matter the descriptions and allusions he was given, his wife said he didn’t really get it and he trusted her. It’s a Brazilian thing. She asked if not speaking to your family was American. She’d go no more than a couple days without speaking to her sister after a fight, not his once-in-blue-moon calls to his brother and sister. What about America? Do you miss that, she asked often. Yes, he said, but never could say why.

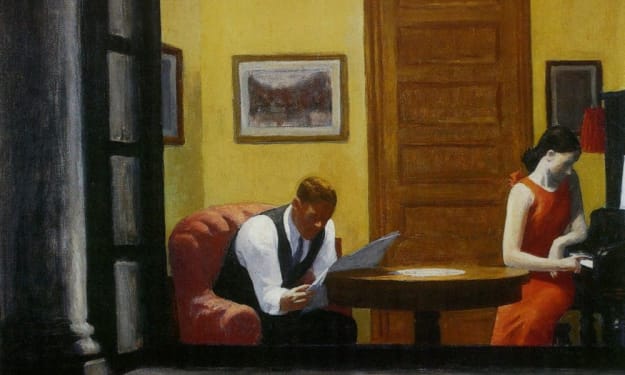

Trying to explain himself was an act of translation itself. Sometimes, after his daughter went to sleep, he described a profound experience or feeling to Giovanna, always rendered insignificant by her reaction and his own realization of what he said. Allan never felt more at home and lost at the same time than at the Iguazu Falls, the mist collecting around him like a sphere, the falls like spiritual organs playing deep eternal tones, a frequency to sound his heart and shatter it. When he said it aloud in their apartment, he formed meaningless syllables, and what for? She was there; she’d been there four more times than him. He chalked it up to feeling unsatisfied with his work; other times, being a stranger in a foreign land—even on days where he joked with her family in time with their fast pace.

More frustrating were the daily miscommunications, reactions, explanations or justifications of his actions and his feelings. He was expressive, sure, known to swear at a stubbed toe—and sometimes he heard his voice rising in the heat of the moment as if listening to someone else, but she called him the “most dramatic person in the world,” or simply “dramatica.” He didn’t think he’s earned the title. If he asked her to not use that tone, or word, or to ask him to do something, instead of ordering him, she calls him sensitive. It was a recurring narrative and no matter how calm, collected and easy-going he acted, she called him out at what seemed to him any hint of emotion.

He’d try to speak and drive through the chaotic streets, other drivers constantly passing and cutting others off from all different directions. “Maybe I’m not using the right words to say what it’s… how it’s happening inside me. Because it doesn’t feel so dramatic, internally. You know what I mean?”

“Not really.”

“It feels like…shit, shit.” He broke hard and extended his arm over her like his mom used to.

By 30, he still hadn’t published a work of his own, and the magazines that accepted his translations had an eclectic style, a global emphasis, and at worse, a fetish for anything foreign. None of it spoke to the quality of his work. But he was mostly happy to eat churrasco and pao de queijo. Maybe the problem was he didn’t see things the way other translators did. They were always on about in forewords and interviews with the New Yorker or Charlie Rose, talking about the active creativity and imagination necessary in fitting the words, lyricism, images, cultural associations and meaning into a new language. Synthesis, not osmosis, they said. He was amazed he was a professional translator at all. For him, he felt like he had to understand who the author was, then what he was trying to say. That was it, that was all.

Allan didn’t return until his parents sold his childhood home. He flew into JFK, rented a car and drove two hours upstate to collect any leftover keepsakes, miscellanea, and memories before they were swept out, dug up, painted over and he was locked out. His room, then “mom’s studio,” stopped being his room a long time ago, but standing in it, smelling it, he appreciated it as his last chance to be there.

He helped his mom and dad pack up the built-in shelf of books, cassettes, VHS, CDs, BluRays, etc. into the cardboard boxes, weeding out the insignificant, and those that could not be easily played or transferred into a new medium—what a labor of love that would be. There were some, like their Sandlot VHS, that he kept just to have. His mom’s famous college textbook was there, a history of human art and the authority for the family’s discussions, trivia and arguments about art. E.g. Was Gauguin considered an Impressionist? What differentiated Dadaism from Modernism? See how hard it is to paint hands, even the masters hardly could.

Allan didn’t realize how strange his family’s fervor for critical analysis was until he went to college. He found there was a shortage of people who cared to speak at length, or as much length, about what a piece meant, or what a detail among the piece meant. One time, his family spent an entire evening analyzing the significance of a pot and its position in certain scenes of a Chinese movie whose name he could no longer remember. They’d rented it from the Blockbuster on First Street. When his younger brother, Dan, declared English as his major, Allan’s dad said, “That’s it. Our fate is sealed.” It was a joke; they’d all become English majors, Dan, Allan and their older sister, Elise, but perhaps it also referenced their mom’s anxiety about who would take care of them when they were older. But with an Art student and valedictorian for a mom and a Calvinist, English and Psychology double major for a dad, what could you expect?

Currently, Elise was hanging off the edge of a rock face in Washington. Allan knew via social media. He didn’t dare show his mom. She’d come down safe and sound, sell rock climbing gear at the REI and write more poetry in the style of Ezra Pound. Abstract, a touch of inhumanness. Allan recognized a multi-centric stance, like Szymborska, but without the sentimentality. Not a single word of it published online, only handmade prints run by a friend at a small press circulated around a group of like-minded ascetics.

For his part, he slept in a sleeping bag that night.

The next morning, in the last hours of waiting around to hand the keys over to the new owners, Allan became the translator for his sister’s work. He was sitting at the table, drinking coffee out of disposable Styrofoam cups and reading Elise’s zine. He’d asked her for what she had done recently and he’d sent her some links a while ago. When Allan’s mom saw Elise’s name on the cover, she stopped stirring her drink and asked Allan to read it to her. He reads the words aloud, measured evenly, weighted with indifference and precision.

“I don’t get it,” she said.

Conceptual and abstract art weren’t her strong suits, Allan knew. Her favorite were the Impressionists, the harmony of the color and shape, and West Coast pop artists, their bright storefronts, plain portraits, those pastoral visions painted with an eye that seemed to put it all within the frame. Still, Allan ventured an explanation, “It’s an interplay between matter and semantics, right? ‘If you see sunset, say sunset.’ That’s the distinction between words and what they represent. You see?”

“Read another one.”

Allan knew his mom. All she ever wanted was communication and agreement, sometimes at the expense of total honesty. She would always look down at her lap when Allan argued with his dad about politics. Elise would only smirk and later, a few times, tell Allan he was right.

After he finished the second poem, his mom asks, “Ok, so what’s going on in that one?”

“It’s similar, I think, but it adds time to the discussion. As in, what is now is not what it always was. ‘The conversation about plants is a dead end’ and earlier it references how rocks are formed, right? The labels are temporary…a matter of context.”

He read a couple more. Midway, he wondered if it was okay to read the poems to his mom without his sister’s permission. It was like his fear of heights, feeling his stomach churn with every word he spoke, toeing closer and closer to some edge. After each reading, he interpreted its meaning, wary of his mom’s worrying.

“Doesn’t she sound lonely in that one? You don’t think it’s like a…cry for help or something like that?”

“No, of course not. What in this has been at all literal?” He laughed. “You have to separate the author from the narrator.”

His dad came back from errands with a box of donuts. Allan unplugged the coffeemaker and took it out under his arm. His mom balanced their cups and his dad locked the door behind them. They ate on the front stoop.

For all the emphases on not just seeing, hearing, and reading, but understanding, Allan’s family has a collective memory of miscommunications. His mom loved bringing them up when they’re all together to laugh about them together. And even though it was a ritual of sorts, his sister always ended up breathless and his dad wiped tears from his eyes.

A favorite was about Allan. He had always wanted a lawn to run around on and fall into, look up at the sky from, to take it all in. And once, after some childhood disappointment, he sighed despondently and said, “Why can’t get a lawn?” His mom reacted, “Don’t say that! We do get along.”

Another time, his mom agreed, “Aw, I loved our lives too,” but his dad had effused about the knives.

But the real misunderstandings happened over and over again. His mom’s worry had to be translated into Dad’s confidence or else the former felt unheard; the latter, questioned and attacked. And only a year and a half apart with his sister, growing up turned into a series of fights followed by, what seemed to Allan to be, longer and longer silences. His dad would sometimes use his psychiatry tricks on Allan, adding “or something” to offer a way out of his interpretation. “Have you been feeling sad about what happened with Sarah? Or something else?”

He had him take the Myers-Briggs, a helpful list of labels and explanations for his desirable and undesirable behaviors. As a teacher and former pastor, he’d encouragingly substituted passion for hot-headed and sensitive for insecure. Please Understand Me II was more direct: The ENFP uses perception as their primary mode and often has a hard time turning it off. He or she can insightfully pick up on a mood or hidden character, or imagine personal slights or subsurface opinions that are not there. Whenever his dad settled a fight between Elise and Allan, he made her apologize and asked him to try to be less sensitive. It always offended Allan.

About a year ago, Elise went on a 1,000-foot climb without a harness. Their mom asked Allan to talk to her out of it. She thought she was being reckless. Allan thought it was something else though. “It’s just something she has to do Mom. She’s a professional climber—she can take care of herself.”

Allan decided to stop in New York City for a few hours before taking a cab to JFK. Unlike his younger days living in the city, when finding some tucked-away bookstore, underground speak-easy or warehouse party was it, he thirsted for the crowds, the tourists looking for a spectacle. He got off at 42nd street and allowed himself to be cut off and pushed around. Everyone sweating onto each other. Today, it was part of the appeal. He passed Moonlight Diner, hearing the dynamite and overpowering vocals from dreamers singing show- tunes only one of them maybe would sing on a stage nearby. In front of Madame Tussaud’s, he saw people taking pictures with the wax figure of Johnny Depp, circa 1990, when he had the long, flowing hair, and lithe and rebellious look, innocently betrothed to Winona. They gave him kisses on the cheek. Some men make fake pistols with their fists and fingers and stand like buddy cups, others pose like him, mocking his severe expression. If it were Allan, he would want it taken down.

On the flight home, Allan peered out the plane’s window, understanding and not at all how big the earth is, and fascinating in its detail. He remembered a couple hours of a day 25 years ago when he and Elise carved a small cave out of a bank in their backyard, and led a hose through the dirt and crabgrass, making a home for an imaginary hero behind the waterfall. The past, Allan knows, has a life of its own.

He followed the signs to the baggage claim. His first time visiting here Giovanna had already come two weeks before and he had to speak English to the employees and passengers to find his way around. Now, he could ask people for directions if he needed them, but he knew his way around. Past the spinning bags and strangers, there was Giovanna, standing like a chorus member in the back of the stage and searching the distance. He recognized, in that moment, her eyes blank and staring directly at him, Allan was.

About the Creator

Paul Fey

I just want to be the best writer you know.

https://paulfeywritings.cargo.site/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.