“Did you know the water in New York isn’t Kosher?” asks Matt, right brow and cheek firmly clamped around the eyepiece of a microscope.

Erika is making a note about something she has just observed through her own, and doesn’t look up from her writing to snippily reply, “that’s a myth.”

“Is not,” retorts Matt.

“That is so a myth, just like there being hundreds and hundreds of rat hairs inside every spoonful of peanut butter or whatever,” says Erika, again, still not looking up from her writing.

“Okay Erika, you tell that to the tens of thousands of Jewish New Yorkers who had to install water filters in their homes following the revelation, and all the restaurants who boasted filtered water to attract Jewish clientele, and all the federal filtering regulations that New York City decidedly does not comply with.”

“Are you even hearing yourself right now?” asks Erika, underlining an observation she had been copying into her daily report with a little too much fervour.

“Yes. And I’m hearing cold hard facts. It’s not Kosher.”

A sudden quiet falls as the bickering pair await the usual, mediating reply from the third body occupying their lab space. Over the past two weeks, Charity, the third body, hasn’t said much altogether, but she has always piped up in times of quarrel with a softly spoken end to things.

The prologing silence causes Erika to stop writing, and Matt too unplugs himself from the microscope to swivel round in his chair, orienting himself towards Charity’s desk in eager anticipation of her decree. He knows he’s right, this time.

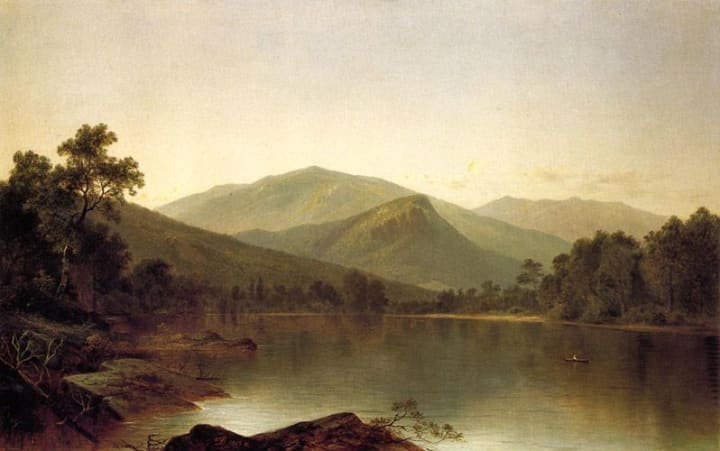

In peeling themselves away from their work, both Erika and Matt unwittingly catch a glimpse of the great body of water that stretches out beyond the panoramic windows that make up one length of the lab; Lake Henrie, the reason for their stationing.

It’s a beautiful, motionless body of water, lined with lusciously dark, green coniferous trees. The shoreline closest to them can only be observed by walking right up to those huge windows and looking down; the building which houses the lab has been built snugly and contemporarily into the rocky terrain behind them, with the lab space jutting out from that landscape like the dormant head of some glass and steel beast.

Charity herself seems to be caught up in the view. Evening is just falling in that lilac way which betrays the previously rainy weather. None of that sunny starkness, no redness in the sky, just a light, dusty purple which will give way to grey and then later, night. Her eyes are wide and she has a hand clamped furiously to her stomach.

Despite the stalwart and consistent nature of her intellect, Charity has always had a very nervous disposition. As if that wasn’t enough, her nervousness has spitefully manifested itself in sharp, stabbing, lower abdominal pain all throughout her academic career. The hand-over-stomach is a more than familiar gesture for Charity, basically automatic. It had to happen when she was cross-legged and eager at primary school, and it had to happen in the many, many lecture halls she dutifully sat towards the front of as she aced her degree in microbiology.

With age came a certain mastery over the affliction though, and for the first two weeks of her stay at Lake Henrie, even with the added pressure of inserting herself into a trio, Charity hadn’t really noticed it. It had been present in pangs of course, as always, but not to the point where her arm had robotocially had to rise in that familiar, comforting gesture.

This is what Charity is going over as she stares out at the lake, as if the answer to her worsening nerves might also lie underneath its surface, alongside the billions and billions and billions and billions of mysteriously unique bacteria that she and her peers are currently researching.

After a moment, the shroud of her thoughts thins, and Charity becomes aware of feeling two sets of eyes upon her neck. She whips round on the spinny chair and uses the motion to force her arm back into a casual position.

“S-sorry guys… I was just thinking about… neuro-muscular junctions…”

“New York City water,” Matt says, legs splayed out, gesturing to Charity with his pencil, oscillating on his chair slightly as he shifts his weight along the gap between his right and left foot, “Kosher, or not?”

“I-it’s not Kosher,” Charity replies without missing a beat. She looks towards Erika to try and assess exactly who this information will be letting down, having paid zero attention to the conversation leading up to Matt’s question, but Erika just has a slight furrow in her brow. Worry.

“I TOLD you!” exclaims Matt after a dust settling second, springing off of his right foot to now complete a whole swivel on his chair.

Erika hears him and blinks a few times, still trained on Charity, momentarily paused in concern.

Shortly enough after this pause though she blinks herself into a shake of her head, a toss of her hair and a fold of her arms, “if only you just sounded a bit more serious when you delivered your facts...”

Matt is lost in ecstasy and lets out another ‘woop!’ as he propels himself across the clean, white laboratory floor, pushing off against the edge of his desk with his arms. He knew he was right this time, but the scoreline from the past fortnight is heavily weighted towards Erika - you have to celebrate where you can.

“There are little crustaceans in the water supply,” Charity continues, “c-copepods… Most of them are too small to see but some, are like, half a millimeter, and you can see those as little white specks in the water… sometimes…”

Having pretty much waved Matt off already, despite his continued wheeling about the floor, Erika is back writing up her notes for the day. She doesn’t look up to acknowledge Charity’s ongoing words, but the twinge of concern from earlier does make her say, “perhaps you should have some water yourself, Charity,” to her peer who had then looked so girlish and small, clutching her stomach on her wheely chair, feet not touching the ground.

“G-good idea…” murmurs Charity, already setting her pencil down and getting to her feet. She is so demure Erika could have probably instructed her to stab herself with that very pencil just then and she would have complied.

Leaving her desk, passing the many cabinets of test tubes, petri dishes, pipettes, tube racks, centrifuges, heat chambers and various other examples of high-end lab equipment that make up several stations around the large room, Charity makes her way to the wall at the far end.

Inlaid into the surface of the wall is a small screen with a keyboard interface, and then an indentation about the size of a dumbwaiter directly to the right. This piece of equipment is decidedly more high end than every other thing in the room combined. It’s a chronic symptom of Coady L. Henrie’s financial and scientific prowess, a terminal reminder of the high calibre the three budding scientists’ work is meant to embody, a symbol of the reason for their stay.

Coady L. Henrie is a genius. And a millionaire. And a philanthropist. Lake Henrie is his, the whole body of water and acres of land surrounding, purchased outright and with no quibbles about any of the paperwork mere days after he had initially discovered the unique bacteria which inhabits its waters.

For the first couple of years while his own lakeside facility was being built, Henrie had to undertake agitated research in a laboratory thousands of miles away, getting samples flown back to him on an almost daily basis. Once it was complete, and living quarters installed, the outside world and outside laboratories made no more sightings of the lake’s eponymous scientist, not even so much as a research paper.

Five years after his hermitage and ensuing silence, the top scientific universities of the Western world received a briefly written notice that Henrie would be offering three, annual residencies to the top performing microbiology students of that year. The residencies would be three weeks long, though if the research undertaken by the young minds was satisfactory enough, Henrie would invite them on to become full time members of his Lake Henrie research team.

This is how Erika, Matt and Charity came to be where they are. Swivelling on chairs, tapping pencils against desks, and punching codes into the material producing machine inlaid into a wall at the far end of the laboratory.

Charity finishes punching in her personal identification code and then the code for ‘water’ when she is struck by another bout of severe stomach pain. Her hand flies to the location of the pain, as though she hoped it to be something she could shape and mould and pull out from underneath her skin, as a little, hot red ball.

The machine seems to be taking longer than usual to Charity, who had previously marvelled at the quickness at which it had produced things like ‘hydrochloric acid’ or ‘sheep blood’ or ‘monkey spinal fluid’ from its internal mechanisms, somehow. Although this delay could well just be because Charity has hinged the relief of her pain on consuming this water as fast as possible, like the act is imbibed with good luck, somehow, because it was Erika’s suggestion.

Eventually, with a woosh, a tall glass of water appears. Charity takes the glass with her spare, trembling hand, and drinks the whole thing down in one. Then she punches in the code for another glass to take back with her.

When she returns to the cluster of desks, Matt and Erika are discussing their end of day reports, the usual routine before all three retire to their domestic quarters. They’ll meet again at the end of the day for a canteen dinner, but they agreed to leave the work, the strange squirms and wriggles of the Lake Henrie bacteria, in the lab, and so will only make smalltalk over food.

“I still think the structural similarities to Clostridium Botulinum bears examination,” says Erika, acknowledging Charity’s return with a little nod.

Matt taps his own notes, “we circled over this for like the whole of the first week and got nowhere though. We saw no sporulation in anaerobic environments, at like every temperature we tried.”

Charity finds can’t speak. Pain. Hand. Sip of water. Why is this making her so nervous? They’ve done this every day for fourteen days.

“True... but perhaps it’s not the anaerobic environment which triggers the production of spores in this case.”

“If we had no other leads I’d say sure Erika, let’s do some trial and error,” Matt taps his notes again, “but we do. Exactly like I said to you guys yesterday, we still need to look more at this aggressive mutation in body cells I observed four days ago…”

“You observed that once Matt,” Erika sighs, “after how many tests? That’s an anomalous result, it must have been contaminated-”

“Lake Henrie water sample contaminated with what exactly? This lab is pris-tine… Honestly if we ever do get to meet with boss man I’m gonna tell him you said that.”

Charity sits, and winces, and sips, and winces, and keeps her hand clutched over her stomach. Now less like she wants to rip the ball of pain out, and more like she wants to keep it suppressed and stuffed in.

“Listen, if you had any sort of better developed theory as to what prompted the mutation, I’d entertain it, but we gave you the scope to do that for two days after initial outlier observation and you came up blank, you couldn't replicate it. And… Let me guess, despite our set objectives this morning, you’ve wasted yet another day trying to do this again,” Erika says, scolding.

“It’s the best lead we’ve got!” Matt replies, flinging both his hands up in defence.

“And stop calling it a lead! We’re scientists, not detectives in some crime drama.”

Charity sucks in a shaky breath, exhales, senses her intervention will be expected soon. The pain in her stomach is pulsating, throbbing. It hasn’t been this bad since she was little, but she soldiers on.

“I-I think there is some credence in what Matt is hypothesising... It was an observable mutation… We did both see the aftermath of those cells… Though that’s not to say we shouldn’t be… trying other things…”

Both Erika and Matt turn their attention to Charity at the wispy suggestion of sound her voice makes. However, where they have come to expect this quietness just as a result of her disposition, now they can both see it is because she is practically doubled over, sucking in air through her teeth, one arm pressed so fiercely into her stomach that her elbow is sticking out, bony, at practically a right angle.

“Are you alright Charity?” asks Erika, transfixed somewhat by her odd posture.

“I-I’m fine… I just get these… pains…” Her speech is punctuated with laborious inward breaths, sucked in through her teeth, “I-I get nervous.”

“Oh Charity,” Matt says, rushing up from his chair and taking the glass of water from her spare hand, “why didn’t you say? You could be having a panic attack.”

“He’s right,” concedes Erika for the second time that day, “take a sip of that water and then tell me some things you can see in the room.”

Matt can feel the surface of the glass is slippery from the nervous sweat evidently coating Charity’s palms, and he feels sympathy for her as he helps her tilt her head back, guiding her into taking a sip of water.

“I-I can see computers,” manages Charity after her sip, “a-and three pencils…”

“And?” urges Erika gently, still bothered by the girl’s posture, and the weird, ragged breaths between her sentence fragments.

“C-centrifuge… Notebooks… Wall… L-Lake Henrie…”

Charity suddenly jerks forwards, and Matt steps back in alarm.

“I-I think… I’m gonna… b-be… b-be… sick,” Charity gets her words out before her body is consumed in an extremely violent heave, the kind that you have no control over, the kind that’s all body and muscles retracting and hurts from deep, deep within.

“Oh my word…” mutters Erika.

Charity heaves again and rocks forwards out of her chair. She stands bent over with her hands now anchored to her knees, her body still shuddering with each gag that rampages upwards from her abdomen. Tears are streaming down her face with the effort of it all. The heaving is emanating from somewhere deep within her, forcing her mouth open, open, expelling nothing currently but the sheer bodily effort required to undertake such a violent gag.

“I’ll go get help,” Matt says after he too had been stunned into inaction, “this has got to be more neurological than a panic attack.”

Still Charity heaves and cries. The pain is overwhelming, sharp.

Then there is a new sensation. Something dreadful, and foreign. Charity heaves and she can’t close her mouth anymore. Something is in there, wedging it open. She heaves again and it moves up her throat, further, wider. Another gag, and another, still they course through her whole body, her stomach muscles tearing themselves agonisingly to force whatever it is upwards, outwards.

Charity can eventually sense something cold, wet and clammy inside her lips, preventing her mouth from closing. Tears track down her cheeks, half out of pain, half out of terror, and only then does she move her eyes to look fearfully, apologetically at Erika.

Erika is too scared to scream.

Matt is fumbling with the code to the laboratory door. It’s repeatedly denying him access, he hasn’t looked over yet.

There is another heave.

Two coral-like rods burst through the place where Charity’s eyes are, leaving sinew and other pink globules of human matter dangling down the girl’s cheeks. The thing in her mouth shoves itself outwards, further. At the same time there is a cracking, threadbare noise as a fibrous mass forces itself out from underneath Charity’s ribcage, splitting open her stomach as it does so.

Viscera and blood, bright yellow bits of fat and pink spongy intestines, all contrast starkly against the white, white laboratory floor.

Maybe Charity screams the sensation of all this, maybe she doesn’t.

It’s hard to tell with her mouth full.

The fibrous aggregation begins molesting the floor, tendrils flailing around the blood and leaving strange circular patterns in its wake. It is now more a thing of its own than a thing of Charity, whose body hangs limply about its form like some sort of sick decoration. Her legs hang either side of the pulsating, writhing mass, feet not touching the ground.

It starts making its way towards Erika. Matt still can’t open the door.

-/-

The ensuing guttural sounds of screaming, bones being broken, joints popping out and general human desperation barely make it through the thick glass that lines one wall of Coady L. Henrie’s observation office.

Situated above the lab, Henrie could have seen everything if he’d wanted to, like the first few times, but he’s seen enough for today. Another successful graduate programme, three more permanent employees.

This time however, it really has been a success.

He’s finally cracked it. The thing which makes his lake full of bacteria so special.

It’s not just that consumption of the waterborne bacteria, voluntarily or otherwise, can cause extremely belligerent mutations in living tissue. It’s that these mutations are very specifically triggered by the presence of cortisol. The stress hormone. It must be.

Erika and Matt had been getting the same, bacteria infested water whenever they went up to the machine too, at the end of the day. And the only thing Charity had which they didn’t, was her incredibly nervous disposition.

Poor girl.

About the Creator

Amelia Lane

Trying my best.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.