St. Peter's Cross

From the Wreck of the Titanic

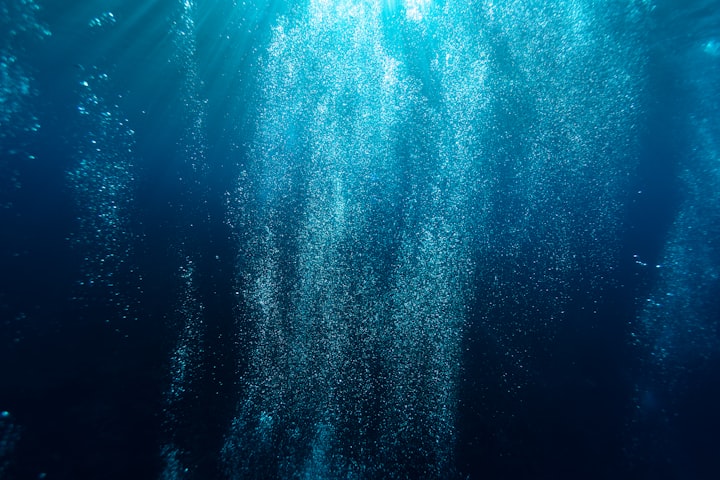

It is blue all around when Robert Buxton awakes. Dark blue, almost black, but with softer spots here and there that gives the darkness accent and informs him of its true color. The next thing that he realizes, a few moments later, is that there is something clamped around his neck, just under his chin, and that he is upside down.

When Robert was younger, if he awoke in strange and life-threatening circumstances, his brain would spring to life instantly. Adrenaline would electrify his form and spur him to action, pure energy filling every nook and cranny as fast as lightning.

He is old now. The pathways within him have calcified. The electrical process of fight or flight has slowed, like blood diffusing into water. ‘Oh Dear,’ he thinks, and that’s all he can muster.

As awareness drips through his brain he finds himself possessed by a peculiar weightlessness, and then he feels the sting of salt in his eyes, and then through the blue he sees what has become of him. Half an ocean liner sinking slowly, two unfortunate beams of steel bent and twisted so as to lock Robert in place, tethering his fate to that of the ship.

As per usual, as soon as his brain begins to grasp the present it starts to wander into the past. He hasn’t gone senile, not the way his mother did, but he is old. He spends more time reliving years past than he does trying to engage with the present. There’s nothing wrong with it, in his mind. The present has no use for him, and the past is like a warm blanket.

He thinks about being in the military, back half a century ago. Green countryside, grey skies. His patrols were pleasant, if you didn’t look too closely at the farmland. It felt almost like home. It wasn’t, not truly, the air was different and the locals unfriendly, but it was much better than a posting in boiling India or freezing Canada. Green countryside, grey skies. The colors were so vivid, green grass like a field of emeralds, like all other grass was just a distant ancestor, blood diluted by lesser plants. And a grey spectacular in a way no grey could be, shades and whorls in the clouds and in the rocks that contained the best of white and the best of black, sweet melancholy made visible. Robert stops, in his memory, and breathes it all in. He can’t recall if he did that when he was actually on patrol. It doesn’t matter. In the memory the colors are brilliant and the air is sweet.

The memory fades, returning briefly to the sinking ship and the cold sea and the steel around his neck before he is reminded of Marcia. A Catholic lady, Italian stock. He was apprehensive about that at first.

He grasps at a moment as it floats within reach. Marcia’s hands on him, water up to his ankles. He can’t move very fast anymore. His body has slowed even more than his mind has. An alarm is sounding.

Getting old is difficult. Robert thought it would be easier with children, and he supposes that it was, but in another way it was just a different kind of difficulty. There’s a certain humiliation in being something’s father and to then be forced to lean on that same delicate thing when your body begins to break down. It was better with Marcia. His son made the arrangement and she was paid with Robert’s money, but having her as a buffer helped ease Robert’s insecurity. It’s better to have a stranger help you bathe yourself, Robert thinks, than shame yourself in front of your son.

His son. He can’t recall his name. A jolt of worry hits him as he sinks, another slow drop of blood spreading out through the water of his body. He knows how the name feels, what it reminds him of, the indescribable taste of it, but the word is missing. Everything but the word. The human brain trafficks in feelings and humors and words are just marks painted on top. Still, Robert is not at peace.

Robert. His son’s name is Robert. The same as his. Robert Jr. He lets out a deep chuckle and his lungs fill with salt water. The sensation rips him back to the present and he jerks, then tries to cough. At this moment he realizes that he is going to die.

The first time he thought of his own death was in the military, when he was still half a boy. The famine was hard on the locals, made harder by the British garrison stationed so close and always so well fed. Robert was terrified of them, of waking up in the middle of the night to find a sunken-eyed Catholic driving a knife into his heart. They did not seem human to him, in his nightmares. They were demons, enthralled by the Pope and driven insane by hunger. On his patrols, when the green and grey gave way to brown, he would hold his rifle a little bit tighter and avert his eyes from the man-shaped horrors that would stare at him, throwing hate with their eyes.

The fear came back when Robert Jr. brought on Marcia. She was Italian, not Irish (Ireland! That’s the name of where he was), but she was a Catholic. Though he knew the thoughts to be irrational, Robert couldn’t help but imagine the sunken-eyed farmers and patient, metropolitan Marcia whispering in secret, plotting their revenge.

Marcia. Water filling up the cabin. A woman’s voice, screaming his name. Blood pumping in his ear, the stunted panic building.

He remembers something from his time in Ireland. The inverted cross. The Cross of. Him. Robert can’t remember the name. A farmer had been found stealing from the garrison’s storerooms. Robert was on guard duty as the wretch awaited trial, and he thought the pendant around the man’s neck was something sacrilegious. The holy cross turned upside down. He asked the man what it meant.

“Saint Peter’s Cross,” The man said. Saint Peter. That’s right. “He didn’t want to die the same way Jesus did, so he had them crucify him upside down. It means humility. A reminder that we’re unworthy.”

The man was hanged the next morning. Robert can’t remember his final words, just a body swinging. His family came and collected him the a day or so later. They were hungry and shriveled and there were no tears.

Marcia again. He wonders why she keeps surfacing in the soup of his consciousness. Marcia was of the present, a reminder of his advanced age and his failing body. She was hard cold steel and the warm fog of his memory should be anathema against her. There she is anyway.

For the first few months of her tenure he would not accept her help until he had no choice. He would struggle to get himself into a set of trousers for thirty minutes, sometimes an hour, and she would wait until he slumped in defeat to intercede. Gradually he allowed her into his trust, letting her exist in his mind as someone to share the shame with, not someone from whom to hide it. She knew to be discreet about the specifics of her duties. He loved her for that. His son knew of his infirmity, of course, but they never had to talk about it. Robert could, in his mind, remain the strong father.

At least Robert Jr. will live, Robert thinks. And then, in his jumbled way, he remembers Marcia.

Thrown against the wall by a surge of water. Robert was just clear of the doorway, he was simply knocked off his feet. She died on impact. He knows, he has seen death.

And then, as if by magic or divine providence, Robert is reconstructed. The past twenty years have forced him into slow decay but now the fractured and rotting pieces of him reform and reattach. His brain is clear, his words returned, his body fast and strong once more. The sea of memories he has lived in smashes into the present, and then suddenly he can see it all, all of it layered on top of itself, The long stretch of the past and the immeasurable speck of the present and the short moments left to the future. Tears well in his eyes and dissolve into the sea, drops salty water beckoned forth by their vast cousin.

And then before him he sees them. His mother and father. His wife, dead for nearly a decade now. He sees teachers, friends, rivals, spread out as far as the eye can see. The Irishman is there, pendant on his neck, and so is Marcia. Their arms are outstretched, their legs tight together.

Robert mimics them, from his sorry position, his chin locked in twisted steel. Arms out, legs together, upside down in supplication, and among them he sinks, down where the dark blue becomes the true black.

About the Creator

George Murray

Contact me at [email protected]

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.