Summer

In a modestly sized but no less verdant garden courtyard there stood the most obstinate tree James Midsummer had ever had the misfortune to care for. He stood beside it now, roughing the bark with his old calloused hands, then sighing and looking up into the canopy where bits of sky blue were scattered like confetti amongst the many shades of green.

The tree had grown proud in its life (although no one knew when it had taken root), and some said its bearing was haughty, if not respectable. Every branch, knot, and root in the tree’s glorious tableau seemed purposeful and placed so not without some deliberation - on whose part, at least James knew, ‘twas not his. For despite employing great care and skill, every effort made to prune and style would be undone overnight as James lay asleep; on each occasion, he’d wake to find the tree had grown in an altogether different direction, and, as if this were not enough cause for James to scratch his head in perplexity, he marveled to see the detritus of his hard labor also reattached, turning and dancing in the wind and catching the light with such splendor as if to tell him very clearly and simply, ‘No’.

Stranger still, the tree had never borne any pears. It was not for lack of care, nor could it be attributed to the vagaries of weather or to its age. And James, a lifelong gardener, had had much success with everything in a garden, and indeed, in the Royal gardens of Edward III, he could coax any plant, bush, or tree into a fine and admirable friendship. However, at this, his retirement to his humble home in York, the parsimonious pear of his youth was unwilling to offer a hand.

James lifted his tunic, wiped his brow, and stepping back slightly, he addressed the tree:

“Thou hast given us naught but strife. Labored have I, o’er thine roots and boughs. I have tended to thine crown and placed fine food in thine lap. But thou art a miser and withhold thine bounties. Thouest bow to neither saw nor shear, scrape not to pauper or King! Now, at last, thou shalt be undone.”

James lifted an axe and steadied himself before the act; its glittering edge flung small specks of the dying Summer light into the tree’s leaves. At this moment a great peevish groan was heard in all of England. It rumbled in James’ ears, it shook the ground beneath him, it tumbled over the dales, the hills, and out to the sea.

In the ensuing silence there came a whisper, like far off wind in a hollow place, it spun around James as the tree fruited and dealt a pear the size of a small child to the top of his head.

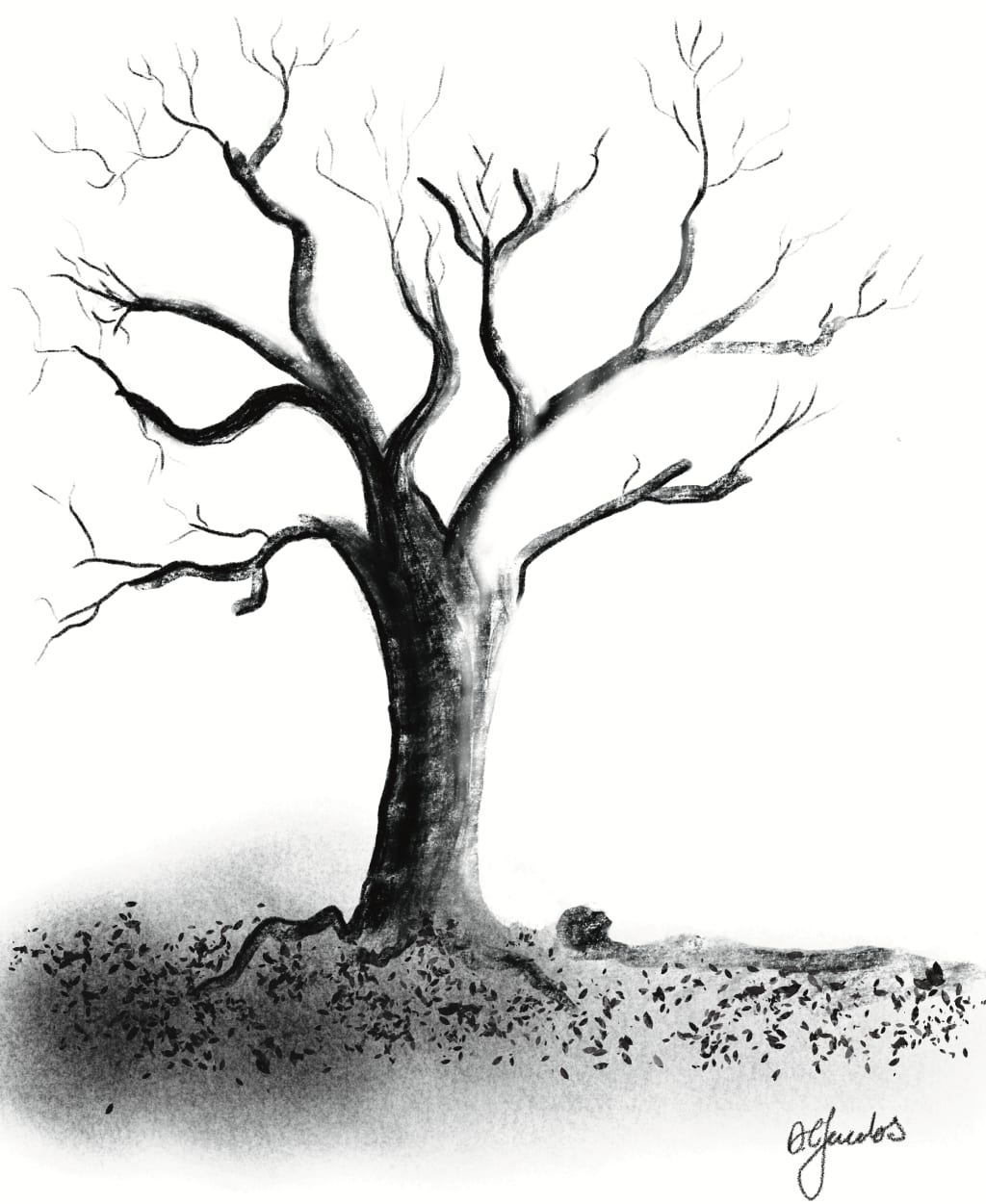

Autumn

During the reign of King Henry the Fifth, extraordinary tales were often told about a local saint of York. True, she was no bona fide saint - neither Pope nor Bishop had ever so much as heard of her. But this venerable woman was instead canonized in the hearts of farmers and shopkeepers, of horse masters, peasants, and other common folk. And this was not only due to her many noble deeds but more specifically for the manner of her burial.

Most of these tales were the offspring of wild imaginations and pious hysterics, not helped, one may say, by a particularly ferocious mead offered in taverns across the county. Some said a great mound had risen around her, enshrouding her body in the ancient rites of Celtic Kings. Others believed instead that her corpse had, at the moment of her death, been transformed into sweet-smelling flowers of a kind that could only have been divine in origin. This last, has within it, the germ of truth, and although the true story of the passing of Mother Eda is perhaps a little more prosaic, it is no less special:

The children had been watered and fed, the pigs in their sty had had their rations (although with far less clamor than the children), and the geese were doing an admirable job in the vegetable garden - in short everything and everyone was well cared for by three o’clock in the afternoon. Now, having set the bread to prove near a warm hearth, Mother Eda took her seat under a vast and gracious pear tree as was her wont after the many chores of the day. She had brought a blanket with her, now on her lap, to ward off the nascent bite of Winter as England began to withdraw from its unusually long Autumn.

“To live four-score is for some no small burden, dear friend,” said Mother Eda smiling and looking up into the tree’s canopy. She drew the blanket to her chin and placed her wrinkled, gentle hands underneath.

“For I though, 'tis no common blessing to give love to so many little eggs, for all these years of mine hast been in their service, and God’s truth, no Royal benediction or Lordly glory near match the joy of seeing a child well-grown and to live and love in turn.”

A robin had flown to a branch above Mother Eda and regarded her with a curious ‘cheep’. The tree swatted it away with a young stem, but Mother Eda did not notice this, her eyes were now closed.

“But thou and I art one in kind, old pear,” she said softly, “For thou and I hast never fruited, not from thine boughs and tender stems, nor I from my womb.”

“No matter”, said Mother Eda smiling again. “For as I have mothered them, thou hast been one unto me all these long years”

Mother Eda became silent and her head was limp upon the tree; it turned ever so slightly following the beck of the Earth and thereupon she moved no more.

The rabble of children did not mind such a long time for play. Nor did they dare to ask why they had not been called. Only when the sun began to set and their little tunics felt too thin to front the cold did they trudge towards the cottage that was their home. No fire had been made, no tallow had been lit, and nor was there the familiar smell of baking bread for the morrow. A frosty dark room loomed over them all, breathing a bitter loneliness into their hearts. A few of the very small began to cry but an older boy by the window suddenly shushed them:

“Soft!” he cried, "Come and look"

There, by the tiny cottage window, the children stood transfixed at a most extraordinary sight, for in the little garden courtyard was Mother Eda tucked into the finest blanket of delicate pear blossoms they had ever seen, under the old barren tree.

About the Creator

D. C. Jacobs

I read a great deal, and I find extraordinary comfort in beautifully written works. Books are indeed a gift - unique and reflexive, continually giving to and back from our kind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.