Sand in the Soul

A Surgeon's Journey from Superficial Cuts to the Depths of Humanity

I have always been sailing close to the wind, or, as my uncle once said, 'You are the stone in my shoe.' This was when I crashed his car as a teenage driver and managed to wiggle out of trouble by convincing him to take the blame.

And ever since, I thought it was cooler to be a stone in someone else's shoes than to step into the shoes of others.

It all changed suddenly.

As a three-time divorcee serial cheater, I was looking at how the (much younger than me) ladies occupied the Mediterranean beach near Kos. For no reason, I felt bored.

From my seat at the bar, I had the perfect view. Young, tanned bodies – tight buttocks, implant-enhanced breasts and joie de vivre were in plain sight.

Then, the picturesque vista broke into screaming, running and rushing chaos. There was a body in the water floating face down slowly towards the beach. The barman had a wry smile when he told me, "You know, these refugees come in waves, and there goes my daily wages".

In minutes, the beach was empty, the bar was empty, and my head was empty.

I walked to my hotel and decided to fly back to London, cutting my holiday short by a good two weeks. But the sight of the drifting corpse burned into my retina. A skinny young man, wearing only worn-out Calvin Klein underpants, had unwillingly turned his back on life, on the future, and on the possibilities he had been dreaming of in some dreadful refugee camp in the middle of nowhere.

As a surgeon, I had seen death. Why was this one different? As a cosmetic surgeon, I had seen people trying to cheat death, but I thought it was their business as long as my business was well alive and kicking.

I have made old hags believe they could turn back the time. I have cynically helped young girls to enlarge their tits – for nothing. I have tactically empathised when a wealthy mother wants to fix her daughter's nose to be more presentable. I have let my knife cut the flesh, sometimes creating a mess but always getting away from the murder of the genuine beauty of diversity.

And now I couldn't shake away the picture of a nameless, faceless lad I had never met. His dead and famished body was alive in my mind.

The airport was a congested and smelly gathering of sweaty tourists who, like me, had chosen to leave the bodies to be collected by the locals from the waters.

Finally, I was in the air and going home.

I had been watching BBC World News at the airport while waiting. The refugee crisis was growing by the day. I felt uncomfortable.

It is different to see the news online than to see it happening before your very eyes.

"What," I asked when the bloke beside me said something. I wasn't in the mood to talk, but the man continued, "Did you see the bodies," he asked, and I nodded.

The rest of the flight was torture. The man kept talking. He thought that the whole refugee crisis was because the Arabs were second-class people and deserved to drown. "I have been working my ass off, and then when I want to have a well-earned break, I have to swim in the middle of corpses," he continued.

I said I was tired, closed my eyes and pretended to sleep.

I wasn't anymore on an aeroplane. A strong wind raised dust, sand and the smell of death, and I couldn't open the door of the strange and shining glass-walled building that rose from the desert sand.

I knew that I could be safe from the storm in that tall building, but there was no door handle or anything that I could use to pull the door open. The sand went everywhere.

My eyes, nostrils and ears had sharp and painful sensations when the grains of sand tried to enter my body like millions of micro knives. As I felt the sand closing in, suffocating me, the door suddenly swung open.

I fell inside, and I was in the middle of a dimly lit hall. It was silent and calm. I was kneeling on the hard, cold floor, wiping the sand off my face, hair and ears. I saw a barefoot man standing in front of me. He was my saviour.

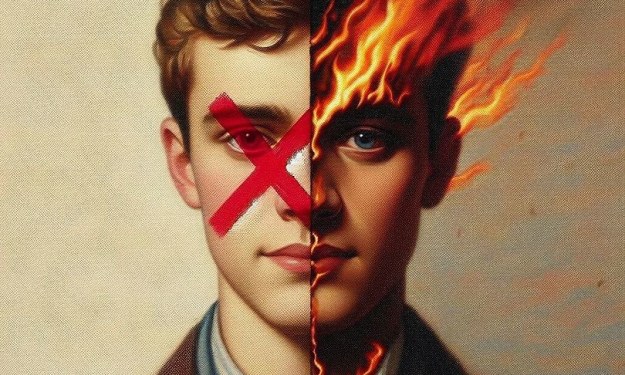

My eyes travelled from his ankles upwards until I saw worn-out Calvin Klein underpants, his only clothing. I jumped up, scared as hell, and there he was: the drowned young man holding my hand, helping me up. Instead of a face, he had a mirror. I saw my screaming face reflected on it and felt somebody push me hard as if trying to break my ribs.

"You had a nightmare, mate," said the passenger next to me, still poking me with his fat fingers, "put up your seat; we are landing".

After endless queuing at the immigration and then trying to get a taxi instead of sitting on a tube, experiencing other travellers and their scents, I finally got home.

I opened my door and climbed up to my cosy urban sanctuary overlooking the little square in front of the Kew Garden's tube station. I needed to have a shower.

When the hot water gently washed away the dirt of the travel, I started to feel alive again. I saw how the soap bubbles licked the hair on my chest, and the steam filled the shower. I was home at last.

But it wasn't over yet.

When I opened my luggage, the smell of Kos, the Mediterranean Sea, and my hotel filled the hallway. I had forgotten that, in my haste, I had stuffed my togs, wet beach towel, and jandals in the bag without putting them in plastic bags. Now, everything in my bag was moist and somehow covered in sand from the beach. My Calvin Klein underpants were wrapped around the jeans, and then I took the deepest breath of my life.

My underpants were precisely the same model as the dead refugee had on him.

"It could have been me," I said to myself. I had to sit down. The floor felt cool against my naked buttocks. I saw myself in the mirror that the interior designer had so tastefully added to cover the wall from floor to ceiling to give some extra space for the narrow hallway.

I saw a middle-aged, good-looking surgeon on the floor, reflected in the expensive mirror. There was sand on the floor, and I pressed my Calvin Kleins against my chest.

I knew that I could not sail close to the wind anymore. I was no longer capable of becoming a stone in somebody else's shoes. The young, dead man had to grind the stone into sand.

My life had been a desert. And I wanted to change it and make it an oasis for others. I wanted to travel back and not escape my responsibility of being human. I knew I needed to let go of my ego and finally become one with the world, a speck of dust or sand, but part of the whole and let the rain of human touch make the desert alive again.

My knife should, from now on, heal, not peal away reality.

I smiled at my reflection in the mirror and knew what I wanted to do because, otherwise, engulfed in the desert's parched silence, I was nothing but another grain of sand in the wind.

About the Creator

Jussi Luukkonen

I'm a writer and a speakership coach passionate about curious exploration of life.

You are welcome to subscribe to my newsletter, FreshWrite: https://freshwrite.beehiiv.com/subscribe

Comments (1)

Very interesting captivating story