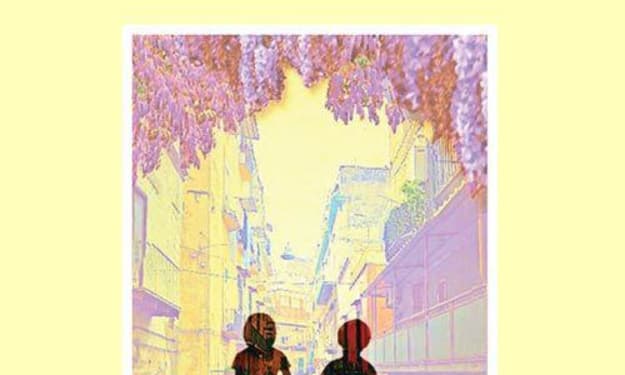

Marco Saverio Loperfido, "Claude Glass"

A Calude Lorrain old expedient

“The landscape architect places himself behind what he wants to portray and thanks to the convex mirror he sees it all enclosed in front of him. Don’t you find that there are similarities with your way of looking at Italy, that is, through the lens of my gaze, placed behind you over time?”

Those who in the eighteenth century portrayed landscapes in watercolor used claude glass, whose name recalls Claude Lorraine. The claude glass was a small convex and blackened mirror, to be used by positioning with the back turned towards what you wanted to paint. The mirror created a better framing of the scene and a softening of the colors that thus took on a languid shade. It was also used by travelers of the time.

Claude Glass “is also the title of Marco Saverio Loperfido’s debut novel. The novel refers to the tradition of the “simulation of truth” with the expedient of finding the manuscript or letters. Specifically, Claude Glass is the name of a junk shop in which the protagonist, Sebastiano Valli, finds, locked in a drawer of a piece of furniture, a letter written by Robert Grave, an English young man, who arrived in Italy in 1792 to do the Grand Tour, that is, that educational tour financed by the parents that the children of the good Anglo-Saxon society used to carry out. Driven by a bizarre impulse, Sebastiano replies to the letter. Thus begins a fabulous correspondence between two men who live two hundred years apart from each other. Robert and Sebastiano become friends, they deepen their mutual knowledge, they open their hearts to each other, arguing and making peace, as often happens in real and virtual friendships. Even Hollywood has exploited the gimmick of the correspondence displaced in time in some films, Alejandro Agresti’s “The house on the lake of time” comes to mind, itself a remake of a Korean film.

The divergent times of Sebastiano and Robert will get closer and closer, the beloved women will have the same name, until the conclusion that, while leaving all the possibilities open, it suggests the probability of an overlap of the two. Perhaps Robert Grave is just a projection of Sebastiano, his need to see reality with the eyes of the past or, better still, to “go back” to the past.

Yeah, “see”. Because the subject of the novel, and of the correspondence, is the landscape. It is surprising that the do not tell each more details of their life and existence in each other’s eras. Everything is based on their way of perceiving what surrounds them, that is the landscape of Tuscia. The author, Marco Saverio Loperfido, deals with visual sociology, that is, the investigation of social phenomena through photographic images. And our two protagonists, the contemporary one and that of the eighteenth century, are interested in capturing aspects of landscape and local life, one through painting and the other through photography. The landscape investigated, as we have said, is, in the wake of Pasolini, that halfway between Tuscany, Umbria and Lazio, that is Tuscia, which Loperfido has mapped on foot. And if he is Sebastiano who looks around and tries to find the beauty in what he sees, Sebastiano is, in turn, Robert, who walks through valleys, hills and towns, places still of great charm today, very picturesque for the English wayfarers in search of Claude Lorraine views. This walking is used to recover the slow and intimate gaze that our current speed has taken away from us, to rediscover, savoring them, glimpses of authentic beauty, in the midst of modernity that disfigures and makes everything ugly.

“This is my time, Robert. Waste and neglect are close to art. But maybe what more … maybe I’m a little too tender. That palace is a scar on the wonder of the past, a scar on the cheek of the Mona Lisa, a blasphemy for those who love Pan, the god of nature, or Venus, the goddess of beauty. I am indignant, disgusted, annihilated by all this which, unfortunately, is only one example among many. They raped the past, they denied it, they handed it down to us altered so that we could not love it. But the past was too good and it continued to speak to us, albeit with a faint, agonizing voice. “

Philosophical reflection mixes with sight and considerations. Sebastiano wonders if what today appears ugly and ungainly to him will perhaps acquire charm over time. And he also wonders if the ruins of the past should not be left prey to vegetation, which perhaps degrades them but makes them part of the planet, while what is preserved in a museum, cataloged, fenced, actually stops living and belonging to it.

“Claude Glass” is a novel that can be read on many levels, for example the glaring one of the denunciation: Italians destroy their land, ready to sacrifice beauty and nature on the altar of necessity. They are the least attractive parts of the book, because they take on the tone of clumsy invective, even foul language, while, on the contrary, the profession of love that both protagonists, the remote and the contemporary, express with heartfelt tones for our Italy rises to lyrical heights.

Another, perhaps less evident but certainly not negligible, level of reading is that of the virtual correspondence, so frequent in our social era. Who doesn’t have a friendship or a love on the web now? Robert and Sebastiano grow fond of each other without seeing each other, they yearn for an encounter, which may or may not happen, but they also quarrel, squabble, separate and then get closer. Many of us have had the good fortune and suffering of living friendships like this, made up of souls that merge, who aspire to a closeness that will never have the fascination possessed by the imagination. There is a lot of Leopardian poetics in these words of Sebastiano:

“Knowledge is an obstacle, dear Robert, because vitality is nourished by fantasy and fantasy by the unspoken, vague, uncertain. Here, however, there is no more space, both physical and mental, and, let’s face it, that’s what I envy you. You are young but, what is even more beautiful, the world you live in is young and accompanies you and supports you in enthusiasm. “

And again: the book is also a metaphor of loneliness, of the impossibility of achieving a profound communion with the other, although this yearning never ceases to recur.

“Robert, it is a defeat for me, and perhaps for society as a whole, that I do this thing today unthinkable: to write a reply to this letter of yours suspended in time, and lost in time, which came to me by chance. It is a defeat because it means that here, alone like you on that April 7, 1792, I am a stranger to my people, forced by loneliness and individualism to attach myself to this game of the soul. Pretend you still alive able to read me. “

Melancholy, the “spleen”, runs through the whole text, vibrates in the epistles of the two friends separated by time, and tempers the hope, which is also present in the recognition of the still evident enchantment of the landscape, in spite of man.

“After the world has danced and danced for so long, now it is tired. Here is what I can tell you about the future, Robert, this and nothing else. You are at the beginning of the dance and I, perhaps, when everything goes out. “

Perhaps, in the end, Robert and Sebastiano will merge, past and present will coincide in a new perspective based on respect for nature, for art, for beauty.

The most lyrical, pictorial, visual parts are linked to the rediscovery of the landscape, which make you forget small flaws of style, such as the annoying recurrence of Tuscanism “te” instead of “tu”, out of place in the mouth of an Englishman.

“At nightfall, with the light of the sunset, the spirits of the places leave the shelters and return to inhabit the lands today as always. It is the transversal light that works the miracle. Shovels, pylons and barracks become only dark shadows against the light and the eye seems to be able to accept them. Everything becomes grazing and confused. The gold of the sun floods the view and Italy, at that time, truly becomes itself because it is the light that is in Italy, unmistakable and unique, its most distinctive character. And light, thank goodness, nobody can ruin, not even wanting to. “

About the Creator

Patrizia Poli

Patrizia Poli was born in Livorno in 1961. Writer of fiction and blogger, she published seven novels.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.