Charm Offensive

A Short Story Under a Spell

"Potestates et affectiones ligatae. Cordis veneficae est ubi celat. Adiuva eam per agoniam eius benedic memoriam eius."

Ruth heard these strange words emanating from her daughter's bedroom, followed by strangled sobs and the wild grunting of some sort of animal. She assumed there must be an awful film streaming on that bloody computer. She and Harold had to pay through the nose for "decent Wifi" so that her daughter could waste her time this way. She filled her lungs with a storm of invective and opened the door.

She wished she hadn't. For just a moment, she wished she had never opened any door.

The stench was vicious. It was if someone had boiled a corpse in a toilet.

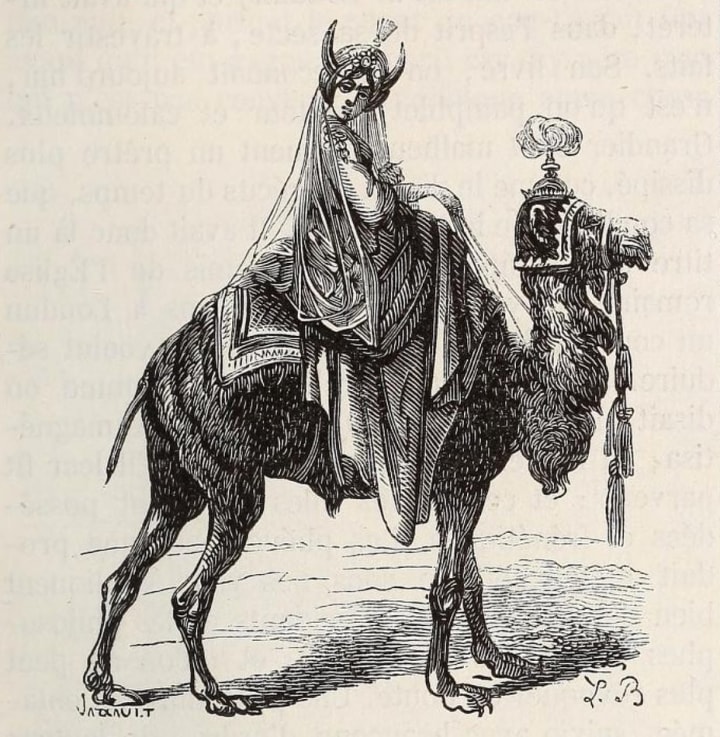

Looming over the twisted form of her daughter, Menassah, for whom she would have drunk a sea of tears, was what appeared to be a beautiful woman, swaddled in exotic silks. She was balancing a ridiculous, glowing diadem on her head like a chandelier on a match. She was sitting on a massive, rotting camel, which looked at Ruth as if she had come late to temple. The animal was doing terrible things to her daughter's writhing body. The woman atop the thing seemed pleased, if mildly bored.

Ruth was very good at yelling. She could singe her husband's hair at twenty paces with a yell. She did not yell. She screamed. She screamed to stop the last drops of innocence from being wrung out of her exhausting, little life.

The apparition dissolved. She threw herself onto her daughter, whose eyes were as white and dim as eggs. She wrapped her arms around Menassah and sobbed. She looked at the screen of her daughter's laptop, seeking some sign that sense could be made; hoping it could and doubting that it ever would be again.

An email was open on the screen, which was spattered with something Ruth hoped was not her daughter's blood:

Dear Menassah:

Haec tibi, Gremory, pro nobis operae recompensatio est. Bibe abyssum, et refrigerare.

All the best.

"Harold!" Ruth's yell must have been audible in Tennessee. "Something terrible happened to our daughter while you were busy watching football, you idiot!"

Ruth was surprised by the desperate scrambling of her husband's shoes along the hallway. She could not remember the last time she had seen him run.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“I am finding it harder by the day to hide my contempt for you.” Her voice was firm but not angry. Menassah couldn’t believe she had said it. Microseconds later, she was elated that she had. She felt her career sliding into darkness, but it had already begun to do so, especially thanks to the pandemic. She loved questioning and debating and struggling to find the meaning of poems and novels and plays and stories. More and more, her students did not read, and just wanted a clear slide where the meaning was spelled out to be memorized. So what the hell?

“Menassah, I think that was really unhelpful. I find your aggressive attitude offensive and, in a sense, traumatic.” Jillian Simmons, the Chair of the English Department and Menassah’s imperious boss, was livid.

Menassah laughed in response. It was shocking. It was also delicious. In fact, it was really a case of the laugh having her. A surge of some dimly recognizable form of energy rippled through her. Oh right. This is what it felt like simply to do and say what she wished.

Some mistake this for feeling empowered, but that’s not quite it. Freedom from constraint was what she felt. She was not second-guessing herself or censoring herself or scrambling to apologize for having said something that some, hypothetical person with raw nerve endings where their hair ought to be might find offensive. She generally felt this way doing only one thing, and you couldn’t do it alone. Or fully clothed. She had tried. Many have tried.

She knew she was in trouble. The trouble was, she liked it. It seemed increasingly obvious—and important--that she ought to try to comport herself authentically, which is one of those words that sounded like a nebulous cliché at birth. What she had in mind was a conscious, deliberate effort to be precisely who she seemed to be. So many other humans seemed so anxious to appear to be the right sort of person, as opposed to struggling like mad genuinely to be the right sort of person.

Drunk. She was quite sure she was exactly what she seemed to be in that sense.

"You wouldn't know real pedagogical or scholarly talent if it kissed you." She was proud of that one before she finished saying it.

“Menassah, I don’t think this is a very productive conversation, do you? I mean, I am sorry to point this out in a way that you might find offensive, but you are not special, Menassah. Everyone at this gathering has a complex and poignant story of grief and strife to tell. Why should I bother to listen to your insults? To whom do they really matter?”

Her Chair (she wanted sarcastically to exploit that metaphor, but she was too late) walked away. That was it, she thought. That was the end of this strange parody of a career. Right there. She reached for the vodka. One has a license to get carried away at one’s own funeral, surely?!?

“Menassah, I know you are awake. Why are you such a fraud?”

Her mother had one mood. This was its worst flavor.

“Look, Ma, I did some stupid things last night. Don’t make me do something stupid this morning.”

She oozed out of bed and was grateful that the floor was so cold. It dulled the pain for a moment. There would be more pain. Humiliation. Shunning. Starvation. Immolation.

“Your strange friend called, because she knew I had nothing better to do with my time. What kind of drug makes someone act like that? I mean, I’m very sorry if she’s—Harold, what’s that complicated name for meshuga that nice doctor told us? New row die…”

Her father sounded like these could be his last words, as he so often did when her mother got angry. She had toasted his eight millionth, spiritual funeral last night. She would only get one.

“Neurodivergent. What, is it so terrible to be sensitive now and then? You think punching everyone is going to make them all soft and tender? The world is not your kitchen counter, my cluster of henna blossoms!”

She understood how Electra complexes got off the ground in moments like this. She badly wanted to give her father a large trophy every time he managed to make Solomon sing after lambasting her mother. He knew Ma loved those vintage words so much. They were her kryptonite.

“I suppose your father is right. He certainly thinks he is. Neurodivergent—is that her problem?”

Meredith was a wonderful, wise friend. She was also unapologetically odd. The two often coincided in their little circle. That was the essence of its special charm.

“My friend is concerned about me because she loves me. Is that why you are concerned about me? I can’t tell right now.”

Her mother walked away. It had worked again. But the peace would not last.

She looked at her phone. 13 messages from Meredith. Yikes. Peace shrank again.

“Listen Menassah, I think we need to talk about friendship, and what it really means to you. I mean, I think maybe we differ here, because in my naivety, I believed that you might actually apprise a dear friend and colleague of any serious mishap in some form other than: 'I’m going to get fired and die. I’ll call you in the morning.' Can we agree that moves like that are just not allowed in this game of friendship? Am I getting upset for no good reason? I think we might differ about good reasons, too.”

“I am very sorry for my lousy moves. I’m single. It makes sense.” She tried to remember what she had done the last time she had decided to honor her Ukrainian ancestors by testing the elasticity of the phrase, “One more.”

Yes, there was that trick Meredith and Hannah had come up with. She wondered if they had any ginger. Would her mother cut her if she reached for it across that counter?

“Meredith, look. I think it is time to conjure the harpies, if I’ve got that one right. I told Simmons off pretty colorfully last night. I could go at any time.”

There was a great deal of gasping and sputtering on the other end.

“Menassah, look, you really must understand something. You are the only person with whom I work, instead of doing a chore. Working with you means something to us both. If you have ruined that, I’m not sure I can forgive you, even though I think your clumsy moves are actually quite endearing.”

It was never really clear to Menassah if Meredith was flirting with her or not. Like a few of the people in their little group, Meredith seemed to be flirting with the whole world and nobody at the same time. All of the time.

“I understand that I hurt you and I regret it and ask your forgiveness.” Her tone was flat, mechanical: they both knew the boilerplate by heart. But Meredith was a big fan of protocol, even if it wasn’t accompanied by rapturous enthusiasm. She waited.

“Your honesty and humility are admirable. All right. How can we help you?”

Oh, that was slick. But she didn’t have time to take offense; in fact, she heard an homage of sorts in there.

“You can help me with a memory that shouldn’t be one.”

Something broke on the other end.

Ceramic? Glass? Menassah couldn’t quite tell. Her mother would know. And let you know that she knew. It was almost impossible to love her mother. When you got it right, though--that was it. You would never be hungry or bored, or quite sure which you weren’t, again.

“Memory is the seat of identity, Menassah, as we have discussed many times. Meddling with the individual’s powers of recollection can do permanent, even lethal harm. We adhere to a strict ethical code, and while I am sympathetic to your plight, I am not sure we ought to follow this dangerous path any further.”

Menassah pitied Meredith’s students during conversations like this, of which she and her friend had enjoyed a great many. Meredith had mastered making her interlocutor feel like a dunce for asking a silly question or incorporating a logical fallacy into an argument or mistaking a metaphor for a simile in some dusty passage. It was a talent, but it explained her mediocre teaching evaluations.

“Indulge me for a moment, Meredith,” she said, taking a deep breath and trying to conjure some of that enigmatic energy that had danced through her when she had insulted Simmons. Watching those scrupulously clean spectacles cloud with wrath had been a high point of Menassah's long, thankless tenure as an adjunct in Simmons’ department. “Think of the last time you ran out of printer privileges just before you had to print up a quiz. Recall the last time Simmons read aloud from a scathing evaluation, shook her head and intoned, 'Meredith, this simply will not do.' Think back to that meeting, when Simmons deliberately set out to make a fool of you in front of the snide, chuckling tenured crowd who count on galley slaves like you and me to do most of the teaching so that they can do research and publish and feather their nests while we scramble to stave off eviction and keep the student loan devils at bay. Are you sure this is impossible?”

She counted the freckles on her arm to kill time.

Her mother mentioned at least once a month that she wished Menassah had shown some sense and gone to law school. “I understand that science isn’t your thing; your brother took care of that,” Menassah’s brother, Reuben, was a general surgeon. Her mother would have anointed his feet with her oily hair if Reuben had asked. “But you’re awfully good with words, Menassah, and you have a memory that sometimes shocks your father and I. Why don’t you use what you’ve got to make a little scratch and defend the innocent? Goodness knows no one will pay top dollar for an essay about dead men's poetry.” If she could persuade Meredith to help her, perhaps she would try the LSAT again.

“You refuse to make anything easy, Menassah. We will meet tonight. Bring a casserole, and some pistachios for Dr. Sheibani. She can’t resist them.”

Menassah smiled and pushed her chocolate hair out of her eyes. Now she would have to persuade her mother to make a casserole. She bid Meredith farewell and went to the bathroom to savor a decadently long shower.

Meredith’s apartment was steps from the University LRT station, which made it easy for her to access the library and to make her way to the college where they taught, which was just across the river from the university where Meredith had defended her PhD and Menassah was scrambling to complete her own. Meredith had nurtured dreams of a sterling academic career, teaching occasionally at the college and hoping to rise at the university when her studies were complete.

Now, she taught like mad at the college alone, having been snubbed by the university, in part because she was “squandering her potential,” teaching dozens of classes at a “lesser institution.” Her apartment was spacious, surgically clean and organized and dominated by a painting that screamed at everyone who walked in--Jean-Leon Gerome’s The Truth Coming Out of Her Well, 1896:

It always struck Menassah as rather "on the nose," that painting. She prided herself on coming up with a fresh, clever way to point that out to Meredith every time she stopped by, and today would be no exception: "Which offends the delivery person more: the nudity, or the broom?"

"Menassah, can we agree that there is stark beauty in silence?" Meredith was as quick as an adder.

"Yes, I suppose..."

"Why would you destroy that beauty with a silly question? You know that if a delivery person makes a fuss, I transform them into a fine wine and serve them with bread and cheese to the next delivery person." The wink that followed was diabolical, as was the self-congratulatory chuckling. Like the rest of their small circle, Meredith was at least thirty years Menassah's senior, but she did not treat her like a child; she treated her like a peer. So few people outside their circle seemed to listen to Menassah in this way, though they certainly seemed to hear her.

"What about my stupidity with Simmons, Meredith? I don't want to brush her memory black like a chalkboard; just effacing that hour would probably sort things out. Can we do that?"

Menassah could smell tea brewing in the small, sparkling kitchen. There were wildflowers in a vase on the coffee table. A neat stack of papers waited to be graded on Meredith's desk, which her cat, Newman, was obstinately holding down. His orange eyes blinked languidly at Menassah, framed by his smoky fur. She had always had a fierce crush on Newman.

"We will see what the others think. I am not at all fond of Simmons, as you know. She is a scholar of rhetoric, not literature: a sophist, not a philosopher. But monkeying with memory is a morbid and malicious business." Meredith touched one of the snapdragons in the vase. It wriggled and emitted a tiny, violet flame. Menassah wondered if students would read more assiduously if they could see Meredith do that.

Dr. Sheibani came out of the kitchen with the tea and a plate of cakes. She seemed always to be slightly irritated by something, though Menassah could never figure out what. She wore a grey dress, tastefully accented by a gold pin in the shape of a stylized candle. Her jade eyes read Menassah's quickly. "Recollection is rarely perfect, kid. Are you sure she made as much of this screw up as you think?" She smiled. Her roseate gums testified to her husband's skill as a periodontist.

"She was seriously pissed and made that clear. If we can't fix it, I'm definitely hooped, and I will never be able to afford to leave Ruth and Harold to drive each other nuts without me," Menassah sighed.

Someone buzzed for admission, and Meredith glided to the door and pressed a button. She wore a black sweater that Menassah knew well and faded jeans. A red scarf was clasped at her throat by a lapis broach. Her stocking feet were as smooth and quiet on the floor as Newman's. She pirouetted to the stereo and Paganini started defying the laws of nature with his fiendish violin. Menassah wished she could have seen him perform in the flesh. Could they conjure him?

"Harold and Ruth are as solid as granite, Menassah. If my mother had been half as clever, I would be cleaning the teeth of the oligarchy and my husband would be trying to coax nincompoops to tell nouns from verbs!" Dr. Sheibani sat daintily on the sofa and cast a covetous eye on the bag of pistachios flirting with her from Menassah's open backpack.

"These are for you; they're actually from Ruth, just like this tuna casserole." Menassah handed the pistachios over and pushed the kitchen door open, then slid the casserole into the oven. She wondered if a single, dirty dish was ever left to sulk in Meredith's sink. Lemons were arranged in a green bowl on the counter, next to a voluminous spice rack that was not, as Menassah had long known, entirely mundane. Newman began to sing softly to accompany Paganini. Menassah returned to the living room to give him a proper audience.

Dr. Hooks was bustling through the door as Menassah returned from the kitchen. Her white hair looked like spun sugar atop her warm, brown face. Her inky coat was dusted with the first Edmonton snow, which had predicably decided to turn up before Halloween. "My cabbie was charming," she said with a grin. "His daughter has made him very proud this semester. She is on her way to becoming a nurse, just in time to take care of me." She lunged for Menassah and gave her a frank hug. She smelled like clove cigarettes and mischief. "Child, you are always so dramatic. Must you always be the trumpet and never the piano?"

"I am in a jam. Can you rescue me, again?" It wouldn't do to joust with Dr. Hooks. Sweet humility was her favorite register. Menassah did not have to pretend. She needed the help of these wise women and they knew it. Dr. Sheibani was making the battalion of pistachios beg for a truce.

Dr. Hooks did not bother to remove her coat. She sat down heavily on the sofa and looked expectantly at Meredith, pulling a cigarette from her pocket and raising her eyebrows. It was an ancient ritual. Meredith frowned. Dr. Hooks put the cigarette away and laughed. "I have just the thing, Child. How well do you know The Liber Officiorum Spirituum?"

"You know Millennials like me, Dr. Hooks. We never do the reading."

Dr. Hooks swore gently under her breath. "Of course. I have a charm that will invoke the power of Gremory, Infernal Duke, whose bailiwick is finding, remembering and forgetting. If Dr. Harbach will kindly unclench and fetch me a drink, we can get things moving, assuming that Dr. Gilbreth's as punctual as someone who is obsessed with the study of time ought to be?"

Meredith did as she was bid and fetched a substantial glass of scotch and soda from the kitchen. Newman stopped singing and sauntered over to Dr. Hooks, who beamed at him. "Who is my favorite furry fellow, hmmm? So handsome in your dotage, aren't you? Want to give my husband lessons?" Newman jumped into her lap and butted heads with her.

The buzzer sounded again, and Dr. Sheibani dispatched the last of the pistachios like an assassin bumping off a monarch. "That will be Gilbreth," she said. "We have all we need, though I think Dr. Hooks is troubling an aristocrat when we could easily manage this with the aid of a peasant." She crumpled the bag of defeated shells and went to the kitchen to inter the remains.

Meredith greeted Dr. Gilbreth at the door. Tall, imperious, the eldest of their little group, she wore thick bifocals that could not obscure her dancing blue eyes. Her silver hair was a riot, her black dress freshly powdered like Dr. Hooks' coat. "White, green, red--are we seriously going to add black to our palette because Menassah's tongue is quicker than her wit?" She swanned over to the troublemaker and affectionately tousled her hair.

"I'm sorry, Dr. Gilbreth. I am sure that I could keep a swarm of your graduate students busy for months, probing my various neuroses and self-destructive tendencies. I would like to be able to eat while they examine me, though." Menassah touched Dr. Gilbreth's hand and showed her the candid face of pain and worry. Dr. Gilbreth knitted her brows and murmured sympathetic syllables. Menassah felt the last of her hangover melt, and Newman meowed his approval.

"Very well, sisters," Meredith shepherded them into a rough circle around the wildflowers. "Perhaps Dr. Hooks can reveal her recipe, so we can cook before eating Ruth's casserole?"

The cocktail did not stand a chance against Dr. Hooks. She rattled the bashful, denuded ice and said, "Ink, paper; Bill in Geology gave me some crushed hematite," she produced a plastic sachet of silvery powder, "Dr. Harbach can conquer her fear of smoke and light some sandalwood, and while she is at it, she can fetch a two of pentacles from her trusty deck."

Dr. Gilbreth produced a scalpel and some alcohol swabs with a flourish. "I got your text as I was leaving the lab, Dr. Hooks. Shall I do the honors, or would you like to harvest the red?" She handed the blade and the binding to Dr. Hooks.

"Don't look at me! Newman got me all excited and my hands aren't too steady on the best of days," replied Dr. Hooks. "Menassah, this demon requires hemoglobin as homage. Are you squeamish?"

Menassah winced, but she was willing. "What will this spell do, exactly? I'll bleed, but will it give me what I need?"

Dr. Hooks chuckled. "Yes, yes. This dashing duke will draw out the memory like a Trump rally draws a fool." Newman meowed his approval and they all laughed, save Dr. Gilbreth, who looked as if someone had farted in church.

"A bowl, then, Dr. Harbach?" Dr. Hooks glared at their host. Meredith slipped into the kitchen and returned with a large, black walnut salad bowl.

"Happy to serve, Dr. Hooks," her tone was icy; these two were old rivals, and Menassah suspected that there was some sort of eldritch duel in the offing. C.P. Snow would have seen this collision of spicy scientist and literary luminary coming a mile off. "I am the instrument of your will, as any good host should be."

Dr. Hooks placed the card at the bottom of the bowl and nodded at Dr. Gilbreth. "I will be very careful, Menassah. Think of tenure," she said. Menassah extended her finger over the bowl. Dr. Gilbreth swept an alcohol swab over her finger and the scalpel flashed. She grimaced, but it was a deft cut. A few drops fell onto the card. Dr. Gilbreth had swaddled her distressed digit in a fresh alcohol swab before she could think to ask. Kindness was not something Gilbreth did; it was something she was.

"Now the ink, and Bill's powder, and let Newman stretch out on that paper," said Dr. Hooks. "Once we have the mix, I'll recite the incantation once, then all of you echo. Then Menassah can dip that same finger and copy out the spell in my left pocket--I know dear, Millennial cursive is as oxymoronic as military intelligence, but do what you can--and then we're sorted."

The shimmering powder blanketed her blood, then darkness concealed its sparks. "Gemory invitaris in medium. Tuo servitio nosmetipsos spondemus ac vestrum auxilium humiliter petimus," murmured Dr. Hooks. Newman growled, and the wildflowers withered when the last syllable sounded. Menassah fished an Earls napkin out of Dr. Hooks' pocket. On the back, next to a barbecue sauce thumbprint, was the spell. They chanted the incantation three times precisely. Dr. Sheibani sounded salty.

Paganini was furious. She dipped her finger. Meredith lifted Newman from the carefully pressed sheet. She wrote: "Cogitationes, ideas, imaginum, opiniones; comprehendis omnes eas leviter dimitte." Her last, tentative stroke seemed to agitate Newman. His eyes flashed, and her scrawled text was alight with an identically orange nimbus for a moment.

"Well, hello Newman!" How Dr. Sheibani found time to both publish at such a clip and stream Seinfeld for hours a day, Menassah could only guess.

The air seemed to grow darker and denser for a moment and Newman squirmed out of Meredith's grip and fled for the kitchen. The room's atmosphere relaxed. "You must read that for her, Child. Turn up for a mea culpa and let her have it. She'll have a memory worse than the electorate's, and you will be able to worry about other matters, like that filing you promised to do for me," said Dr. Hooks. She pinched Menassah's cheek. Menassah glanced at the Gerome painting. She was sure, for a second, that the witch from the well winked.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Menassah was sweating in the stern chair beside Simmons' office door. Mrs. Schroeder (she insisted on just that appellation, changing customs be damned) had been the department secretary for at least a century. She glowered at Menassah. Rumor had a thousand wings in academe. Menassah felt she knew what a medieval penitent must have felt under the accusing eye of a gargoyle on some cathedral's ominous buttress. She smiled at Mrs. Schroeder. The look she received in return would probably become malignant myeloma in a year or so.

"Please come in, Menassah." Overture. She touched the spell in her pocket and entered Simmons' lair.

"You know, Menassah, I am not sure there is much to be discussed today." Dr. Simmons sat behind her immaculate desk and smiled thinly. The office was stark ; books bound in dark leather lined three walls and the fourth featured a large window that stared accusingly at the pumpkin spiced quad. The only ornament on the desk was a Folio Society edition of Aristotle's Tekhnês Rhetorikês.

"I'm sure you're right, Dr. Simmons. I am sorry." Menassah sat meekly in the small chair opposite Simmons' desk. "I am embarrassed to be a little nervous, as I'm sure you'll understand. I have written a brief apology. May I read it?"

Simmons looked pleased, if suspicious. She rose. Her lenses seemed to darken. "It may be a pointless ritual, but I am pleasantly surprised by the gesture nonetheless. Do go on." She adjusted her white jacket and smoothed her steel grey bangs.

Menassah trembled. She pulled the spell from her pocket and read, "Cogitationes--"

"Silentio, fatuus!" The Chair had cut her off, and something more. Menassah's teeth were grinding each other to powder. She could not speak, or move, save for the maniacal motion of her jaws.

"Have those bitter biddies taught you nothing about wards, Menassah? Your mind is a dripping faucet. I caught that nonsense about freedom and power the night you insulted me. Freedom is a euphemism for power, Menassah. Soon, you will learn precisely what that means." Her smile was full, and smoldering, this time. She opened the volume on her desk and read aloud, though Menassah could not decode the Ancient Greek.

Simmons' lenses waxed opaque, then turned mirror bright. Menassah could see her own, horrified eyes clearly in those shocking circles. She could not breathe.

"The hour of the witch is here, for those who can seize it. Fair? Foul? Mere noise. 'That's subjective,' i.e., meaningless. The air is literally filthy, and the fog is pestilential. Only one thing matters now, Menassah: outrage. Outrage arises from confusion. Note that the 56th Infernal Duke, Gremory, taught me this. He appears as a regal woman, when he does. Why? To sow confusion, then outrage, then obedience." Simmons touched Menassah's forehead and made a sign on her skin. It felt like she was a herd beast being branded.

"Gremory practically supervised my dissertation, Menassah. Your grizzled grannies know nothing. In fact, I'm not convinced that knowledge matters any more than beauty or goodness or any of the other quaint anachronisms they rub so avidly, like worthless coins. You will leave here and slither back to your vile nest. There, you will find my final word concerning this ugly episode and your broken future. Good day, Menassah."

Menassah could not recall her departure and the bus ride home was a vague pastiche of noise and light. She was sitting in front of her laptop. She remembered Dr. Gilbreth sending her a memory charm, in case things went wrong and she had to restore Simmons' mnemonic faculties. Menassah smirked, despite the ache that caused, and opened Gilbreth's email. A drop of cold sweat blurred her vision for a moment.

Her jaw relaxed. She would have to tell her sisters what had happened. They were unlikely to believe her.

She managed to read out the charm, scrolled to the email that Simmons had just sent, and read it. Her room stank. She was no longer alone.

About the Creator

D. J. Reddall

I write because my time is limited and my imagination is not.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.