The Fading

How do you want to be remembered?

My dad was like a squirrel with his money; he hid stashes of it everywhere. When he died, I found pill bottles filled with change. When I took it home and weighed all of it, there was more than two hundred pounds. It was over $2000 dollars and I used it to pay for his funeral.

As time went on, I kept finding pockets of money...an IRA here, a stock portfolio here, and life insurance policy there. All together, it added up to around $20,000 dollars. It would have been a fun scavenger hunt, except for all the paperwork and phone calls. I got so tired of hearing strangers tell me they were sorry for my loss. I know they were being kind, but emptier words were never spoken. Made even more hollow when given by someone who doesn't even know you.

My dad was young when he died, only fifty-five. He had once been a strong man, tall, hefty, typical Nebraska stock. At his heaviest, in the mid-90s, he was probably around three hundred pounds. The last day I saw him breathing (alive would be too generous a word), he probably weighed less than hundred and fifty. His collarbone stuck out, sharp and pointed, from under the thin sheet. His breathing was shallow, swift inhales, followed by short exhales, some gasping, a little rattling. He died later that night.

I chose for my dad to die. I could make the sentence less...accusatory and say...I let him die. I was even congratulated by the hospice nurse on letting him die the way he wanted to, which was the strangest compliment I’d ever received. But no, there is no sugar-coating that sentiment; his death was a direct consequence of the decisions I made. Yes, I don’t think he wanted a feeding tube; he didn’t want to linger, living a half-life in some nursing home. There wasn’t a better option to take. But still, the sentence remains...I chose for him to die. I signed the paperwork; I made the determination. There was no one else left to make those decisions, but me.

He had a chronic illness, a muscle and brain destroying illness, and he had been diagnosed with it young, at fifty. He truly shouldn’t have been living alone by the time he died. But he didn’t want to be in a home and I didn’t have the heart to force him. The year before he died, his driver’s license had been taken away. Increasingly in the last two years, I had received concerned phone calls from restaurant owners, police, social workers, and the owner of a local hardware shop. They all went about the same, “Your dad fell. We called the ambulance. He didn’t want help.” And that was what it always came down to...he didn’t want help. No matter how many times he put body-sized holes in the walls in his house, no matter how many times he bent his fingers out of joint trying to catch himself, he did not want help. I talked to the social worker and a lawyer about getting him declared mentally incapacitated, but it was an ordeal. And from all outward appearances, my dad was mentally capable of making his own medical decisions.

My parents divorced when I was ten; it wasn't a nasty separation, just melancholic. Two people who had been in love weren't anymore. My mother died while I was in college, so that left my dad and I. My dad was a carpenter; he built custom kitchen cabinets. He taught me to make things, how to measure and where to cut. When I was fifteen, we made a bookshelf to fit in my closet. We didn’t use any hardware, but instead cut grooves into the sides in which to slide the shelves. Since then, I have moved at least six times, and it is the only bookshelf that lasted through all of them. The other plywood things, masquerading as wood, crumpled. But this shelf, stained dark cherry, has not even warped or bent.

My dad taught me about cars, how to change the oil and how to drive a stick. When I was fourteen, I helped him re-roof his house. While I was in high school, he listened to the entire audiobook version of “Anna Karenina” with me, which in those days, was a brick-sized set of CDs from the library. He taught me how to hunt and skin animals, how to fish. The year he was diagnosed with his illness, we were supposed to go Elk hunting in Montana.

I was living in New York by then, working in publishing and trying desperately to fit into a large city I secretly loathed. He hadn’t told me he had been sick; he didn’t mention the weird stumbles, the uncontrollable tremor in his left hand, the way he had to focus on walking in order to not fall, especially when in crowds. He didn’t tell me about the test and the MRI scan, the neurology doctor visits. He only told me when the doctor’s told him it was unwise to go hunting, let alone hiking up the Rockies in search of Elk.

They had told him if he got stabilized on medication, he might be able to function for another three to five years. Then, he would not be able to swallow or breath on his own. I offered to move out there, but he refused. I moved anyway, at least to Des Moines, which was about a three-hour drive from where he was in Sioux City. I saw him every weekend, cleaning his small house and cooking his meals for the week. Both the doctor’s and I wanted him to be in a nursing home, but he refused. Begrudgingly, he consented to home health, so at least someone was checking on him daily.

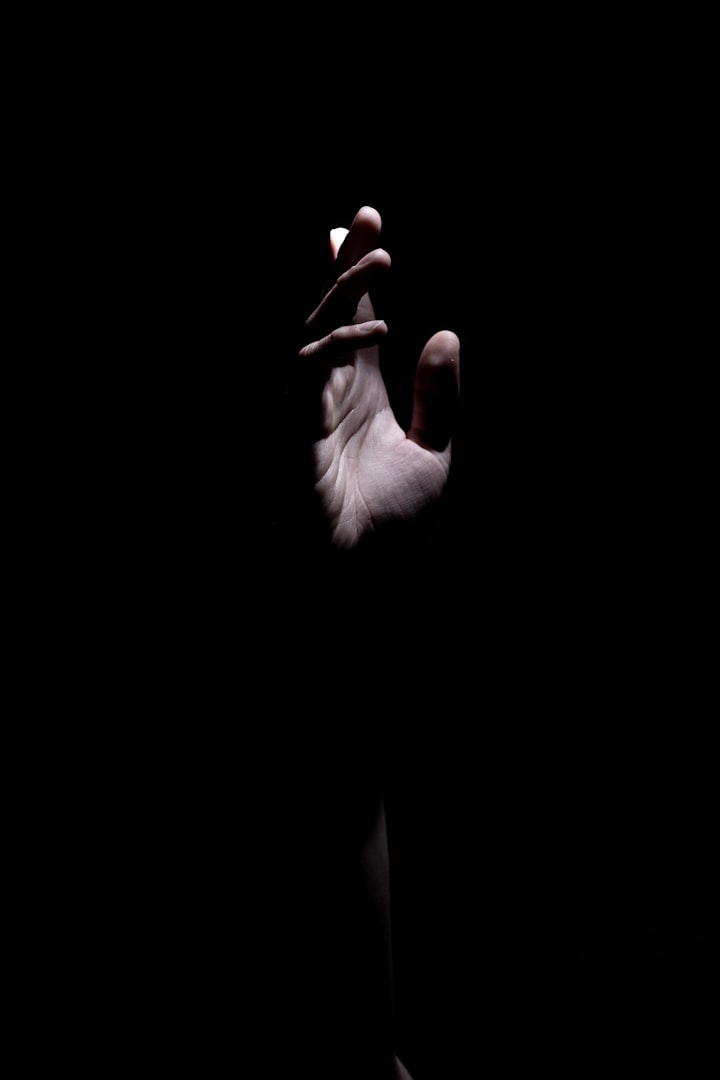

But, in the end, I found him, frail and thin, crumpled in his hallway, fallen. When I saw him, I had this creeping, finger-prickling feeling and a cold, steady realization that he would not survive. So when the palliative care team at the hospital told me he wouldn’t likely breathe on his own after they took him off the ventilator, I wasn’t shocked. I was a little surprised when he kept breathing on his own, but then he couldn’t swallow. Most likely he never would regain the ability. So I made the only choice I could, for him to die.

The week after the funeral, I was sorting through his house. He had cleaned most of it out in the last five years, only keeping the few things he truly cherished, books, dusty vinyl, his tools, the wooden furniture his grandfather had made. While digging under his bed, I found a cardboard box filled with the same paperback-book sized, black notebooks. I assumed they were all empty; my dad liked to buy things in bulk he might one day need. While he had purged most such purchases in the last few years, I had come across some similar stashes as I rummaged through his house. He had four boxes full of shampoo, three full of soap, and a hall closet stuffed with Costco-brand toilet paper.

Sighing, I cracked open the first notebook. Inside was written the same sentence, like a mantra, line after line, and page after page, "If you can't remember me as the man I was, don't remember me at all." Each line had a date scribbled next to it in the margins. His first entry was within the first week of his diagnosis. Flipping to the end, I saw the last date was four years ago. I picked up and scanned all of the notebooks; it looked like he had written, or tried to write at least, the same sentence every day for the last five years.

I could see the devolving of his mind in the pages. The handwriting became increasingly scribbled, hard to read. The first year or two were still legible, but in the last three, the letters became scratched and jagged. The last notebook was almost impossible to read; the sentences scrawled across lines. The last day, the sentence curved down towards the bottom of the page, as though he had weakened even while writing it.

That night, under the purple summer sky, with fireflies flitting in the humid dells near the creek, and the cicadas hissing loudly, I cast all of the notebooks into my dad’s backyard fire pit. I threw in his pill bottles and cane, and the last picture of us, where he was twisted and hunched, barely able to sit straight. Then, dumping lighter fluid on the pile, I set them ablaze. He did not want to be remembered as the disease had made him, so I methodically burned or destroyed anything that would hint at it. And that winter, I went hunting alone for Elk in Montana, with my father’s rifle.

About the Creator

Beth Carlberg

Beth Carlberg is a freelance writer, currently working on her first novel. She primarily writes fantasy and folk horror. You can view more of her work at https://www.wingsandwriting.com. You can also email her at [email protected]

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.