Perfectly Horrible & Unspectacular

The truth will set you free.

I wrote my mom’s eulogy before she died. Well, technically, she was brain dead, and I sat on the hospital bed next to her and penned what I thought were the appropriate things to say about a dying woman. She heaved her breaths — no pitter patter — more like a see-saw with cinder blocks tied to each end. Or like two men in the Pacific Northwest in the 1800s, sawing down the mighty sequoia at a pace not unlike the amount of time it took for the tree to grow. And I sat beside the heavy, small woman and wrote on my phone’s note taking app about science projects, real estate, and how her favorite saying was that she was “sparkling,” in reference to her mood. I cried with guilt that evening, as if I sealed her fate for her; The eulogy is written, no turning back. Even though she was already brain dead.

And after she died, in a church she never went to, under a God she never confessed to, I held the hand of the brother I didn’t get along with and talked about science projects and who Patricia was, or at least how I wanted her to be remembered by the masses. I wanted the rows filled with mourners in black and blue to leave with tears in their eyes and the happy memory of Patricia doing paper mache science projects the day before they were due. What a perfectly horrible intention. What an unspectacular woman.

I left the church with knots in my stomach and watched the hearse take her back across the street in a non-procession to be cremated and split between several small containers and be kept forever, so each time I returned home I could look at the physical minimization of the personality I shrunk in church for the fear of being too real. Too true. I imagined for weeks that she was looking down at me, mumbling and cursing as she often did when alive because I blotted her existence under the guise of good intention. It ate me up inside, consumed my thoughts that I failed to speak the truth on her behalf.

Until I did.

It took several months of denial and only two beers on a ferry across the sound — my academic River Styx — the gateway between the horrible truths of my home and the fluffed up ideals of undergrad. I wrote about the hospital. I wrote about driving through state after state, and taking a boat, and driving some more to see a woman with egg yolk-colored eyes and matted hair stare into my face and say, “What the hell are you doing here?” I wrote about how lucky I was to select a school only a hundred miles away just in case Patricia decided she didn’t want to live anymore. That yes, in my senior year of college, my choice to pick the school I already invested three years in finally proved itself to be the best decision, because my mom finally pushed herself over the edge and I could make it home in only a few hours.

That was my truth. And her truth. The woman who left me on the see-saw with my legs dangling in the air was an alcoholic. During much of the wake and funeral, my dad told everyone she was simply ill, or that she had liver cancer, or that her kidneys failed — all in an attempt to escape the taboo of a successful small-town business woman drinking herself into oblivion. The whispers would have been too great for him to bear alone, and I never blamed him for it. But while she lay in the closed casket for two afternoons and two evenings, I felt as if I was staring into a deep well of secrets that would follow her to her grave. I couldn’t allow that, so I wrote. I described the hidden bottles of vodka around the house, and I wrote about her throwing me into a refrigerator in a blackout. I mentioned the afternoon, just months before she died, when I talked her back from committing suicide. A couple of weeks after that, I went and studied abroad at Oxford. She sent normal emails, happy emails, don’t worry emails.

Then she left.

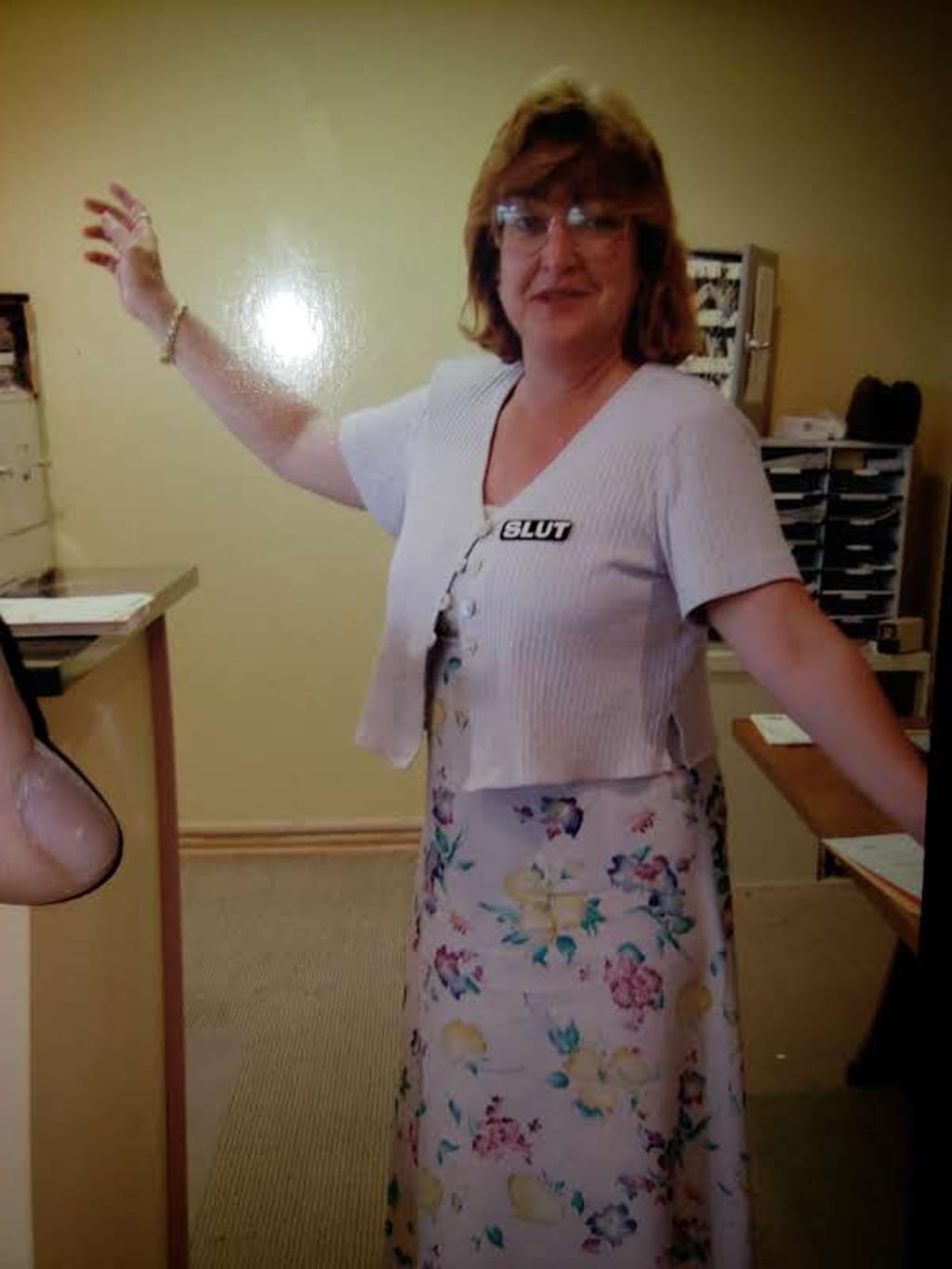

She was an expert at science projects. She always said she was sparkling. Those were truths. She was also unbelievably troubled, but Patricia was far from unspectacular. Never in my life have I seen another woman drum on the steering wheel of a 1984 Toyota Camry hatchback with the vigor of John Bonham, nor have I ever witnessed a middle-aged woman rap horribly albeit passionately to Eminem’s Curtain Call album. I never saw someone talk into a phone with such a commanding voice that she practically ruled the world of real estate in our town, standing on the shoulders of egotistical men in cheap cologne that was drowned out by the scent of her White Diamonds perfume. Never in my life — still never — have I witnessed someone as hard as the liquor she hid from view soften to the needs of childhood friends and feed whoever sat at our table, no questions asked. Patricia wore a name tag that said “Slut” on it for an entire day of work. She made a very detailed paper mache penguin, she taught me how to drive; She didn’t want to live. And she left me alone in the worst way.

But I shared her truth.

I shared it with friends, literary agents, strangers on my blog — the universe. I feared the responses. I feared taboo and stigma, addict non-sympathizers, etc. I also feared that my writing was garbage and that I was no more than the ramblings of my childhood diaries. So when the overwhelmingly positive responses came through, I found myself in shock coupled with pride — and most of all — humbled at the amount of people who told me they could relate. They felt less alone. They wanted to share their stories as well. They felt less horrible in their grieving.

Slowly at first, and then all at once, I realized I was meant to be a storyteller. I learned the value of truth and the importance of telling it to others. I felt an honor inside of me to tell the truth of my mom — someone plagued with demons — while maintaining her humanity. It inspired me to tell the truths of others, like my grandfather, and his struggles in the war. I turned it into a screenplay as well as a book, and an online series on my website for good measure. Then I received a text telling me, “Yeah, I think you’ve found yourself in the right place.” There is no need to hide the truth of others, to make them unspectacular. It’s a secret that festers and holds overhead like a specter, unwilling to leave until it is let go with reality. My mom was so dynamic, three-dimensional — human. Her story was multifaceted and something that many people may not have directly lived, but the crevices of her persona, the events of her struggles — the feelings of her life — are what brought my readers to common ground. I am most passionate about writing truths, and presenting them in such a way that shows the beauty of people without demonizing them for being human. I will spend my life telling stories, and I will spend my sometimes perfectly horrible life speaking the truth.

About the Creator

Kaitlin Oster

Professional writer.

Owner - Shadow Work Consulting, LLC

David Lynch MFA Program for Screenwriting with MIU, graduation 2023

Writing collaboration or work, speaking engagements, interviews - [email protected]

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.