For Poh Poh

我爱你

Before the stroke

Everyday when I look at my arm I am reminded of my grandmother. The jade bangle that lays heavy on my wrist makes me think of her. I haven’t taken it off once in the three years I’ve had it. It was hers, and now it’s mine.

In Chinese culture, jades represent protection and wealth, where the greener it is, the luckier it becomes. It’s an item worn by mostly older generations of Chinese women, as the weight and size of the bangle can make things a little bit complicated. Putting them on and taking them off requires multiple people and lots of lubricant – making it rather inconvenient to wear. Usually once it’s on, it doesn’t come off.

“Why would you let her give that to you? It’s so ‘auntie’”, my mother texted me saying, once she saw the photo of my freshly jewelled wrist.

“I didn’t have a choice”, I replied, “but I like it.”

The jade I wear originally belonged to my grandmother, in fact, the story of how I got it is quite funny. I was crammed into the backseat of a car next to her; we were driving down the motorway, heading to a leaving dinner for me. I was in Singapore at the time, where the majority of my family live, and was heading back home a couple weeks later. My grandmother’s English was extremely limited, and my Mandarin even worse, so we mostly communicated through gestures and facial expressions. She pointed at the jade she wore on her wrist and said:

“You want?”

“Wo de HERE hen da” (my points at wrist is very big), I replied unconfidently.

“No! This very big!” she insisted, forcing my unwilling auntie to help contort her hand, so that the jade could eventually be ripped off.

This took about ten minutes, all as we continued to drive down the busy motorway. But as soon as it was off, my fate was sealed. My grandmother grabbed my wrist, and then suddenly, the jade was mine.

Throughout the whole dinner, my grandmother pointed at my newly decorated arm to show various family members, waiters, and anyone whose attention she could grab.

“She said it looks good on you because your arm is fat”, my auntie translated for me.

Two weeks later, I left Singapore, feeling slightly heavier than I had when I first arrived. Wearing a jade made me cautious in a way I never expected. Every movement I made had an underlying thought that too vigorous a motion could cause it to crack. You see, jade bangles can break, and they often do. In our culture, it is said that if a jade breaks it’s to protect you. If my jade was to break it would be under those circumstances only, not because I was being reckless with it.

Being in Singapore at that time hit me with a wave of motivation that I’d never really felt before. I had spent my whole life thus far not knowing how to speak Mandarin, and even as a child, when my mother tried so hard to get me to learn, I was stubborn and refused. I would constantly tell her I didn’t understand what she was saying (when I very much did), and my refusal, in turn, caused my mother to give up. I grew up in a very white environment, where I was often shunned for being of mixed race. In fact, I vividly remember the first time I was called a ‘chink’ was at eleven years old, and this was by a fully-grown adult male. It’s very difficult being told things like this from such a young age. It makes you think: “if half of me is bad, and I can’t change that, what do I do?”. Most people would probably say that you ignore it. But when you are young and you don’t understand, you are gut-punched into survival mode. You do what you think the only option is: assimilate.

This assimilation manifested itself in many ways for me. Self-deprecation and self-hatred were definitely two of the highest contenders. But my biggest form of assimilation was the refusal to have any part in the side of my culture that I was forced into believing was bad. A significant part of that included not learning Mandarin.

Leaving Singapore that year caused me to realise there was a whole relationship that I had been robbed of. For years, I had had minimal conversation or interaction with my grandparents, mostly due to the language barrier and my refusal to learn. It took a lot of self discovery to realise that my childhood stubbornness had stemmed from bad experiences, and that the way others had made me feel caused me a lot of inner turmoil. As a fresh graduate at the time, I knew I had my whole life ahead of me, which was what helped me make my next decision. I was going to get back what I had missed out on. I was going to establish a new relationship with my grandparents and thank them for all they had given me. I was going to move across the world and come back fluent.

At the end of 2019, I packed my bags and moved to Taipei, Taiwan, where I still reside now. I had enrolled myself at a school specifically for foreign students to learn Mandarin, and had spent months saving in order to afford it. I had sorted out my accommodation, school tuition and necessities, and was more than excited to make the move.

Once I arrived and started learning, I was hit with the realisation that I actually knew more Mandarin than I thought I did. Years of hearing my family speak to my grandparents had worn off on me, subconsciously perhaps, and I found myself not having too difficult of a time with the move. I had less trouble speaking than I thought I would, and managed to fit in with Taipei’s fast-paced environment fairly quickly. I was having the time of my life.

That’s when I found out my grandmother had had a stroke.

After the stroke

My grandmother suffered a stroke just as the pandemic hit. At the time, Singapore was in the middle of enforcing a strict lockdown, which caused her to not get the physical therapy she dearly needed. My grandmother had already suspiciously started losing weight before the stroke happened, and now, she couldn’t eat or drink. It was almost as if her body had forgotten that she was able to do so, which caused her to become scarily skinny and frail.

Over the next few months, my grandmother’s condition continued to worsen, causing my huge Singaporean family nothing but worry. We were all so confused as to how her condition had worsened so quickly, and how she had become cold and dismissive, completely the opposite of her previous joyful and humorous self. After consulting with doctors, we found the real issue. Not only had my grandmother suffered a severe stroke, she also had pancreatic cancer.

My grandmother was the ‘boss’ of our family, and in a matter of months, she would be gone.

By coincidence, in the middle of 2020, my mother, sister and I were all called back to Singapore to deal with some visa issues. For us, we were more than happy to go back, as we knew it would be the only opportunity to see my grandmother again. Despite the pandemic and all its restrictions, we had been given this final chance to say goodbye.

Seeing my grandmother in her condition was difficult to say the least. She had transformed completely, both physically and mentally, into a somewhat stranger. The only aspects of familiarity were her obsession with handing money and jewellery to loved ones, her desire to go to the casino, and the dark green jade bangle, which lobbed around her now incredibly skinny wrist. I was more than shocked when I saw her, and her condition put a lot of stress on our family.

During that time, I argued with my mom more than ever. Sometimes over bigger things, sometimes over nothing at all. We were even stress smoking together, which is not the best bonding experience for a mother and daughter. But things were hard. I was going through my own mental struggles, and my mother was watching hers die. We were both heartbroken, and pushing each other away at a time when we needed each other the most.

“I feel the same way with you like I do with Poh Poh (grandmother)”, my mom sobbed after an argument. “I can see you’re both suffering, but I can’t do anything to help you.”

I paused momentarily and could only offer an “I love you” as a response.

For people in Chinese families, “I love you” is a phrase which is not often said. For us, it doesn’t really need to be said, as it is shown through acts of kindness or helpfulness. But at that time, I felt like it was the only thing I could say to convey to my mother that I understood why we were arguing, and that I loved her all the same.

The end of October 2020 was when I said my final goodbye to my grandmother. Throughout my stay, I was able to communicate with her slightly, but it was more of a one-way conversation. It was becoming painful for my grandmother to talk, and she didn’t have the strength to do so anyway. At that point, I had only learnt Mandarin for 5 months, so I was nowhere near fluent. But I had learnt enough to say everything I wanted to say to her. I told her that I was deeply sorry for learning Mandarin too late. I told her that I only wanted to learn so I could communicate with her and my grandfather. I told her to try eat more, so she could come visit me in Taiwan, knowing full well that that was never going to happen.

I contemplated what to say afterwards, holding the words ‘I love you’ on my tongue. As I said previously, it is not a phrase said in Chinese households, and I felt weird saying it to her out loud. But I knew if I did not, I would regret it for the rest of my life.

“Poh Poh, wo ai ni” (grandmother, I love you), I sobbed, as I held her hand, and she held my jade.

“Wo ye shi” (I do too), she replied quietly, barely able to speak at that point.

And that was it. The next day I left for Taiwan, knowing full well I would never see my grandmother again.

100 days after death

My grandmother died a few months later, surrounded by the majority of our family. In Chinese culture, funeral arrangements are made immediately, but due to the pandemic, my mother, sister and I could do nothing but watch her celebration of life through video call. It was hard not being able to be there, but especially hard not being with my mom. I wished more than anything that I could hold her hand while she cried.

A few days before my grandmother died, it had gotten to the point where even she knew it was coming. She had made very specific requests for her funeral:

1. No hymns/Christian music (she wanted to “sleep peacefully without having to hear it”)

2. A sea burial

3. Lots of flowers

That’s exactly what she got. As I watched her celebration of life through video call, I saw my family all come together to pay their respects to the boss of our family. It was incredibly sad, but we were able to celebrate the wonderful woman who raised us all.

And I know this sounds crazy, but my jade got significantly greener the day she died. “She’s protecting you”, my mother said, which offered me some semblance of comfort.

In Chinese culture, 100 days marks the end of the mourning period. During this time, no celebrations are allowed, meaning all events from baby showers to weddings are off the cards. After 100 days of death, a celebration is usually held, as it is said that at this time, the deceased successfully moves into their new life. This celebration often involves wearing black, elaborate offerings and lots of prayers.

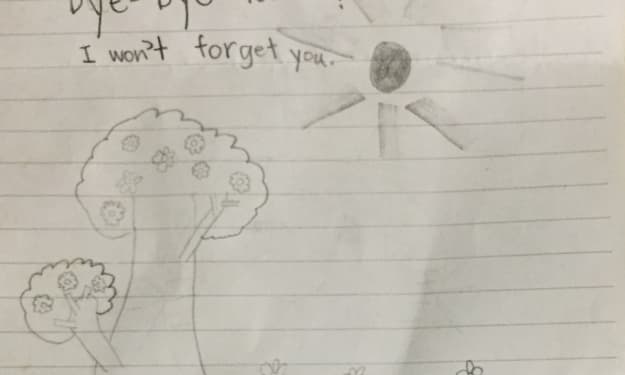

However, my grandmother was never a traditional woman, and so we decided to celebrate her in the way we knew she would have wanted. That meant no sappy songs, no burning of paper money, just a pure celebration of the woman she was. And so, my 50+ member family continued my grandmother’s legacy by going to the sea, to rivers, or anywhere with flowing water. We threw in hand written letters, flowers, sang songs together, and wore the brightest colours we owned. With the pandemic restrictions, myself and the rest of my family living away from Singapore could not attend in person. But with the sea burial, we were all able to be connected by water - exactly what my grandmother wanted. It was incredibly difficult not to cry, but I know she would have wanted me to smile.

So why the sea? Like many Asian grandmothers, mine had an obsession with cruises. In fact, my grandfather told me that a close friend of theirs had a dream that my grandmother was on a cruise going somewhere she would not tell us. She said not to worry, and that she was okay and travelling. Thinking about this still makes me chuckle.

Later this month marks a year without my grandmother, and my family are going back to the ocean to celebrate again. I will have my own small celebration here in Taiwan by writing a letter for her too. It’s hard not to resent myself for not learning Mandarin sooner, but I know that she is proud of me for trying, and I’m glad that we were able to speak even the smallest amount just before her death.

My jade, that she especially gifted me, is a prized possession that I will never take it off. It’s a reminder of who she was in my life, and the strength she brought to our family. Every time I look at it, it makes my motivations grow stronger. I remember that my culture is special, beautiful, and one I should not shy away from, but be proud of.

When people see me wear it, they know I am Chinese. That is an identity that I would never change for the world. I know where I come from, and I believe in the family that raised me to be who I am.

As for my Mandarin, I’m nowhere near fluent yet, but I’ll get there, and I’m excited for when I do.

And finally, to end this, Poh Poh, wo ai ni (grandmother, I love you).

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.