In the quiet of morning’s light, I am convulsed by dissonance, jarring and sudden as a swift-knocking jackhammer into concrete, wrapped in cold wind.

My face feels numb and I close my little black notebook because there’s a ringing in my ears that I haven’t experienced since I was young, and could be hurt suddenly, and then lose all memory of the incident no more than five minutes later.

All around me are sound waves touched by this arrival of an unwelcome crescendo, a feeling of classical motifs building toward a finished movement that crests again and again and finishes with a roar.

As I set my phone down and begin to stare blankly at the wall in my studio with the Goya print of Saturn consuming his offspring, I begin to weep uncontrollably, feeling a shake protruding like a spike from my right shoulder and hammering at my form like bad pieces in an out of tune piano.

I feel my wife’s hand on my shoulder, but I am made up of split wires and cavernous sounds that pour through me, or around me.

***

Context is important in life.

In fact, life does not exist in any shape we would recognize or consider worth living were it not for the context provided by the existence of others.

I cannot say I never loved my father, or that my father never loved me. We did and I still do. But his articulation of the world didn’t lend itself well to words, and though I embraced music, he wasn’t really able to follow me there either.

For his own part, he worked very hard to not be poor – having an artist for a son wasn’t so much a disappointment as a mystification. He had the language of biology, of chemistry, and he dreamed of law schools and hospital residencies for his children.

All I wanted to do was sit at the piano.

“You’re too pale,” he would comment, and walk away.

What could I say? It’s not like there were many places to play Mendelssohn in the sun.

I never expected him to outlive my mother.

In a weird way, I never really expected to outlive him either. The perspective of a parent can feel timeless. When you’re a child, they are a monolith, and, whether they like it or not, a totalitarian: they establish the rules by which you live.

Once a person becomes an adult, they realize that this formerly totemic person is just that – a person, but one with so much time and such a flurry of excitements and regrets and disappointments and successes that you would be forgiven in believing they had existed forever, and would continue to exist until the dissolution of matter itself.

***

I am sitting in an armchair in a lawyer’s office. My wife had offered to come with me, but as with most things in regard to my family I prefer to go it alone.

Not because I don’t want her here. But my folks had a kind of insularity to them, a natural bubble of familial solitude as nuclear as the atoms of Lucretius.

I may as well be in my parents’ living room, quietly making a treble clef in my book and jotting out a few notes that have bumped about my head as the lawyer, Everett Cliff, silently rummages through notes and is diligently ignoring me until he has everything in order.

I’m fifteen minutes early anyway, a lesson of my father.

“Early is on time, on time is late and late is unacceptable.”

He had said that when I came home late one night as a teenager, stoned as hell.

“Why are you late?”

“Band?”

I stop my notation on a rest.

“So, Thomas.”

I wait for him to continue, but he’s squinting at some paper.

“Yes?”

“Yes, Thomas.”

He squints harder.

“Your father has left everything to you.”

“And my sister?”

“She’s not in the will.”

“Oh.”

“Indeed.”

More squinting.

“Aside from the house and the contents, which is modest, there is his savings account. Here are the details.”

I look: the savings account has $20,000 in it.

“Not a bad sum – of course, money does little to ease the pain of death, but, a little extra never hurts.”

His voice sounds like a lazy breath through reeds. My head bows for a moment and I listen to it trail off like mist.

“You’re an artist aren’t you? I saw you perform a few months ago.”

“Oh?”

“My wife,” he wrinkles his nose for some reason, “likes jazz. You certainly impressed her.”

I can’t tell if he hates his wife or jazz. I decide not to commit.

“Well, thank you.”

“It’s very good of your father to support the arts like this. Lord knows they need it.”

“The arts? I’m his son.”

“Indeed.”

***

I spend the rest of the day sitting in a bar down the street from Everett Cliff’s office.

Sitting by the window, I watch people meander down Dundas West, filing along, hats perched just so atop their millennial chic heads, with their dogs, bred into disability.

I put notes in my little black book until my hand gets tired, which takes time. I’m not writing jazz, not strictly. It’s something else, like a lost language.

Maybe it isn’t even my piece. I could just be transcribing something I’m trying to remember from a very long time ago. I feel like a very big mess.

My phone buzzes: it’s my sister, Jen.

“Hi.”

“Hi.”

There’s a big sigh.

“So? What’s up?”

I laugh, I can’t help it.

I take a long draught of my pint.

“Well, you heard right?”

“Yup.”

“Yeah,” and I pause, because I have to tell her, and there’s no way around it: if I do, it’s awkward, if I don’t it’s triple awkward, so I just have another long drink of my pint, and breathe hard.

“Bar?”

“Ah, yes. Bar. Pint. Maybe a whiskey next depending on how this goes. I just talked to Dad’s lawyer –”

She cuts me off.

“I know he didn’t leave anything to me.”

“How?”

“Oh, he told me he wouldn’t. A few years ago. He basically said I didn’t need it – you’re the artist after all.”

“But you’re not tenured.”

“He had blind faith I would be.”

“Not a whole lot of blind faith in this direction then.”

“You know how he was. And what they say about old dogs and new tricks.”

“So what do you want to do?”

***

I only ever really know what I want to do when it comes to music, and certain key elements of my day-to-day life.

I enjoy cooking, therefore I cook; or reading books, therefore, I read books.

And I write music, and play music.

The administrative aspect of everything is a drag for me. On the outside I may present as a well-organized professional – on the inside I am belly-dragging myself to every meeting with labels and agents and lawyers, all of those surrounding infrastructure types who whirl around the process of creation.

My father thought I would be a good entertainment lawyer, because I might understand the feeling of being an artist better, being one myself.

Needless to say though, the mark of a good entertainment lawyer isn’t that they understand you, but that they understand the mounds and mounds of legalese that finds its way into your contracts and then do their best to root out exploitative clauses.

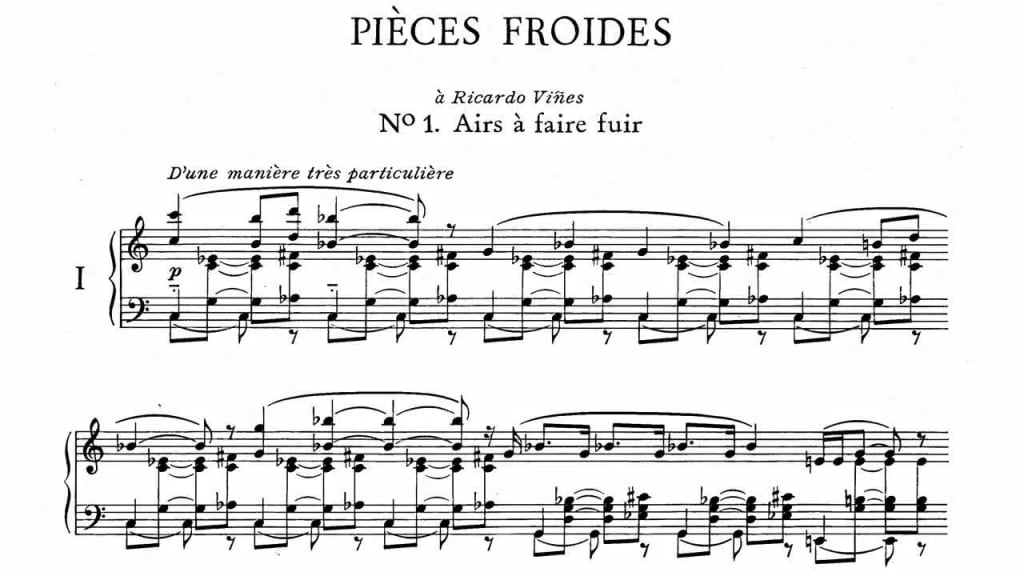

He walked in on me playing Satie one day, the Airs à faire fuir pieces, and actually sat down and watched. I could feel him watching, but I stopped myself from turning to look and tried very hard not to fumble.

I did though, a little slip, a piano player kind of slip where you feel dissatisfied with the result but a normal human, one not versed in music might not realize or recall beyond the next five seconds.

Finishing the piece, I looked back at him, and he was looking at me curiously.

“Did you mess it up?”

I didn’t know what to say.

“There was a note – it should have been lighter but I made it too hard. It came out wrong.”

“So you did mess it up.”

I looked back at him, obviously burnt.

“It’s a good piece though. Keep it up.”

And he walked out of the room.

I just sat there, staring at the floor, until my sister wandered in and told me dinner was ready.

***

Someone once told me that you are never fully grown until your parents pass away. I’m not sure if I agree with that, but there is something to it, and even thinking about it now, I am disquieted and feel ill-at-ease.

In this theory, your parents are always above you in some shape or form. They have this huge, defining role in your life, and continue to have this huge defining role even as an adult.

Holidays are hosted within their family homes, sometimes the home that you grew up in as a child, and their reaction to your presence brings them back into the performance they began at your birth.

Everything becomes semiology, your presence in the home a stand-in for something else, their presence as a host a sign of their continued role as a caretaker, a life-giver.

When my mother and father first saw me play at a music hall, not a bar or a tiny cabaret, they spoke to me afterwards as if they were both very proud of me and extremely diminished by my success.

“I guess you don’t need us anymore, huh?”

My father had said that rather heavily as he plunked his hand onto my shoulder and gave it a shake.

Jen just looked at him funny.

“Dad, you are so weird,” she said, giving me a big hug.

“Didn’t seem like you messed anything up either!”

“Thanks dad.”

“You did good.”

***

I’m writing a check to my sister for $10,000, the largest check I have ever written in my life.

The house is up for sale, and I am eager for it to be gone.

When we walked into the house to go through it, Jen and I, we both spent about five minutes crying and then ran around the inside of it, looking for all the weird notes we left each other on the walls throughout the years.

Down in the basement was my first upright.

I couldn’t help it. I sat down and ran my fingers along the keys as Jen was fiddling with something in the living room upstairs.

I flipped open my little black book and started playing the notes I had been absently pulling from memory and quickly realized, sitting there at my old piano, that they were from Satie’s "Airs à faire fuir: D’une manière très particulière".

It was adjusted here and there by my own hand to give it a jazz-like lilt that crossed the piece and turned its minor key complexion into something slightly funny, though still rather melancholy, and still very far away, something that was at once a part of me and something that had fled into the world.

For a moment I could feel my sister watching me as the music filled the basement where I spent so many of those early years.

The more I thought of my father, the funnier the piece got, as if his intransigence, his suspicion and his critical face, bunched up with all his unanswered questions, was sitting somewhere off to the side, cautiously hoping I not screw up.

About the Creator

Samuel Wilson

Samuel is a writer, theatre director and bartender currently living in Toronto, ON. He has presented theatre work in New York, where he used to live, and Toronto. He lives with his wife and their cat.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.