Cheyne-Stokes Respirations

Gasping for the ending

He fell on July 19th, 2019 while walking the damn dog. After people in the 70’s fall and break a hip, their life expectancy is typically three-to-six months. However, the end did not begin with the fall. His gasping for life began years ago, perhaps even before I was born. Smoking didn’t help but innate self-uncertainty, insecurity, unfulfillment fueled the breaths of discontent.

My dad’s diagnosis was a lengthy process, but in retrospect, he was a textbook example. He was once a math wizard; becoming a pharmacist was his first quest. Mysteriously (something I will forever be haunted by not forming a gang of misfits to solve), he joined the Kansas City Police Department, where he served for 25 years, retiring, reluctantly at 50. Seeing pictures of him in his uniform, clean shaven, lipless, awkwardly smiling, eyes that could pierce the psyche of even my most accomplished juvenile delinquent friends, he appeared geekish, too intellectual for the duty at hand.

When he joined the narcotics unit, he embraced the persona of Tommy Chong’s long-lost cousin, which then created even more of an enigma, wrapped in a conundrum, topped with a heaping of “how the fuck did you pull this off?”

He could memorize maps at a glance, driving to places with an internal compass that pointed true north. He added so quickly in his head that I wouldn’t have even written the numbers down and he had already answered correctly, beginning the next problem. He was always deliberate and succinct in his speech, but his speech was eloquent and to the point.

Prior to the diagnosis, there was always something different. Something quirky. Something unspoken about his energy and persona. None of his seven siblings phenotypically presented as he did.

Gregarious. Risk takers. Room stealers were they.

Measured. Calm. Wall flower was he.

When he could no longer balance the check book, got lost coming home from the grocery store, 1.5 miles away, and stuttered through words of three-to-five letters, when he drew the clock that looked like Dali’s on acid, when his siblings couldn’t make him laugh, my Mom knew.

He was diagnosed with Lewy Body dementia in 2013 and I felt sadness, fear and relief. Looking back, most obvious in pictures and recalled conversations, something was askew, not his normal abnormal. I felt sadness primarily for my Mom, the nurse, who knew what to expect, as sometimes knowing just enough is more dangerous than knowing nothing at all. The fear was for the progression of the decomposition of a human life. The relief came when a diagnosis validated that he was experiencing organic compromise. In this turmoil I pledged to become an active witness to the beginning of the end, the end of his being, and memorialize the ensuing events.

Lewy Body is the parasitic twin of dementia tethered to Parkinson’s. Robin Williams was given the diagnosis of Lewy Body and committed suicide after he was informed the treatment was essentially palliative and the prognosis did not portend for an ending where anyone who loved the patient wasn’t solaced by their departure. The twins are not kind in how they subject their host to cruel stripping of any semblance of their true self.

Eleven days after George Floyd’s murder, I made the voyage down I-35, starting in North Minneapolis. Those previous 11 days were filled with so much emotion and uncertainty, and then wonderment, as our three-year-old wunderkind turned fournager overnight on May 31st, with a 22 pound chip on her 30 pound frame. I was reticent to leave both she and my wife. The strife and uncertainty in our city during the day and quiet unease at night figured into two-to-four hours of sleep per night. When a toddler learns her place in the world and deems our home is now hers, all those factors were brought indoors and no rest was to be had by anyone.

Could I leave these two in such times when one was known for dramatic flares of independence interspersed with bouts of incomprehensible desire for complete and total attention and the other an astute observer of possible catastrophe in a stiff wind or a misdirected sneeze. Genetic pull soon won the tug-o-war of emotions.

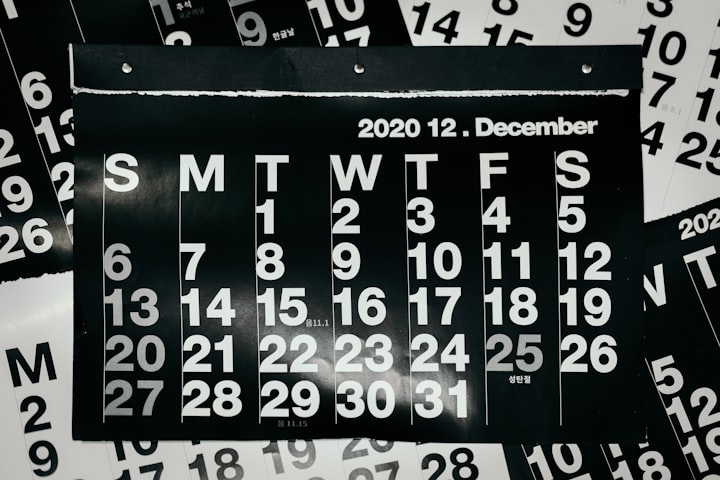

My trip began at 5:28 pm on June 4th. I know the exact time due to the text trail between my mom, my brother and me, which began on the 29th, when my Dad was yet again admitted to the hospital due to aspiration pneumonia. This bout turned out to be the last battle with the inevitable harbinger of death for many Lewy Body sufferers. Having lived in Minnesota for 23 of the last 25 years, the drive down I-35 was undertaken numerous times, in all conditions, environmentally, mentally, physically and emotionally. This trip, the moon was full, the road was clear (a bonus of the quarantine) and I knew there was a good chance my Dad would not be there upon arrival. Before departure, I was informed that the sacrament I had learned about in Catholic grade school, known as “last rites” was now called “anointing of the sick” from the priest who conducted this sacrament.

On four hours of sleep, Mom texted from the hospital that due to Kansas and their lax health regulations, she was sitting in the lobby, of the hospital, not the morgue, as he had somehow made it through the night, with his soul still tethered to this earth.

My brother and I arrived. Reference the lax regulations above, and we were both allowed in the ICU room. My Dad had looked better. He had looked worse. His open-heart surgery three years prior was another step closer to the afterlife. I let him know my evaluation of his outward health. When he responded with “fuck off”, I was certain he was going to live another year.

I stayed for two days. He was no longer on high levels of oxygen support. He was becoming lucid; not baseline lucid, but able to recognize us and eat some high-quality “thickened” liquid.

The palliative doctor educated our family, the physician assistant, the retired nurse, and the hospital based social worker regarding this prognosis. The aspiration pneumonia repeat was not an “if” but a “when”. He was released to home on a Wednesday. Wednesday, June 10th to home hospice with a pharmacopeia of chemicals to keep him calm, low pain and not searching for his police-issued hand gun.

Pneumonia essentially suffocates. You don’t have to have a background in medicine to know how important inhalation and exhalation are to survival.

We can go weeks without food. Days without water. Only minutes without air. As the last breaths are taken from you, or you give them away, (it’s all perspective, isn’t it?) a physiologic process occurs, one in which you gasp for air in a gulping, forced manner. These are called “Cheyne-Stokes Respirations”. Medically speaking, Cheyne-Stokes respirations are described as:

“…disordered breathing characterized by cyclical episodes of apnea and hyperventilation. Although described in the early 19th century by John Cheyne and William Stokes, this disorder has received considerable attention in the recent past due to its association with heart failure and stroke, two major causes of mortality, and morbidity in developed countries”

Furthermore:

“characterized by a crescendo-decrescendo pattern of respiration between central apneas (temporary suspension of breathing) or central hypopneas (abnormally shallow and slow breathing)”

These breaths/respirations are very disconcerting. If you’ve ever watched a fish expire on land, you’ve witnessed a primitive version of this phenomena. And when it is a family member, your father, whose birthday was 25 years and 1 day prior to yours, every breath, every respiration takes with it one of your own.

I missed the last Cheyne-Stokes breaths. The trip down I-35 on June 19th was faster than expected but slower than required to spend time with the man who took is daughter fishing, hunting, taught her how to shoot a basketball and win at Monopoly, after 1,000 attempts.

When the text came from a high school friend, Carrie, now funeral director at the home where all Miskec’s go for their last showing, with the simple “Chris, so sorry. I heard it was peaceful” I didn’t even stop driving.

My own Cheyne-Stokes breathing began, but only until I realized how much easier it is to hear of your father’s passing via text and from a friend then from the voice of the woman who loved him completely and deeply for 51 years. My brother was there. He’s my good twin, 9 years apart. My parent’s dog, Sugar Bear, the one who chased the squirrel, causing my Dad to trip on the curb, and fall with all of his 142 pounds onto his left hip, causing a fracture, another surgery, and the pneumonia saga to begin. My brother said that during the second-to-the-last breath, Bear raised her head, looked out the bedroom door, and ran down the hallway, chasing the energy of her Papa.

By the time I arrived, all breathing was stopped. His body was cold, hard, and looked more lifelike than it had since Lewy-Body took his mind. His blank faces was now expected. His loss of emotion was appropriate. His eyes no longer searching for “why me?”. When caretakers with the gurney from the funeral home closed his eyes, crossed his arms, smoothed his hair, and gently placed him on the hard slab, I wanted to look out the bedroom door and run down the hallway. Instead, I watched as they raised him to a standing position, so tall, so erect, so empty.

We had more in common than in contrast, yet I lived my life to avoid those similarities. And now I strive to breathe deeply, live fully, and never give the breaths the last word. I strive to be full.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.