Another Day

To lose one’s art is to lose one’s soul

For my earliest memory, my grandmother had been a secretive, old wort. Even though I had lived with her from three years old until my twenty-first birthday, I only knew three facts about her. She had once lived in France, my father was her only child and she disowned him upon the death of my mother. I was raised by her, or really lived with a series of nannies in her apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. I hadn’t been back to that apartment in over 20 years. News of her passing reached me days after the event and returning to New York carried a heavy burden.

There were many rumors that swirled in family lore, none of which she would ever talk about, let alone confirm. Did she have an affair with Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian-British newspaper publisher and infamous philanderer? Was my father the result of that illicit tryst? What really happened to her husband, who was whispered to have left after only 6 months into their marriage?

Opening the door to the apartment brought back years of memories, rustled up from the grime and age settled into the walls and furnishings. I immediately headed for her bedroom, the one room that I was forbidden to enter my entire life. I was struck by how small and crowded it was, dominated by a wooden framed mirror hung over a mantled fireplace, with art hung surrounding her bed, neatly covered with a purple and white bedspread. Two nightstands stood on either side, with empty flower vases and a lamp standing as sentinels. I could still smell the German Eau De Cologne 4711 that hung in the air surrounding her.

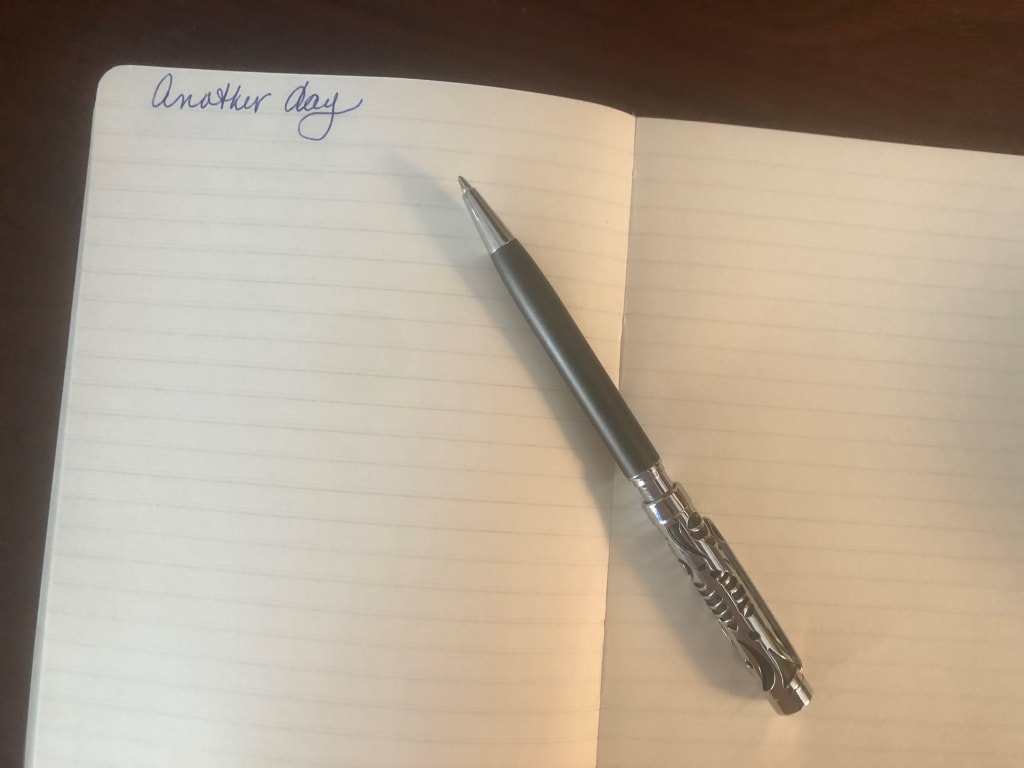

Where to begin? Was her history buried in this room or hidden in scattered nooks throughout the apartment’s bookcases, desk and drawers she so closely guarded? I took a seat on the side of bed and was struck by the firmest of the mattress, offering no spring or comfort. I opened the top drawer of her nightstand, to be greeted by the rattle of pill bottles, an ornate pen and a Moleskine journal. The notepad’s brown leather was embossed with swirls of flowers and the gray marker ribbon was frayed at the bottom. I opened it to the selected page and found my grandmothers aged handwriting, almost illegible now, recording what had been the final days of her life. Each page began with the note “Another Day” and recorded the history of a single date. The book was over half filled with notes of her outings, travel, visitors, dinner parties and thoughts. On her final entry, she noted she was reading “West with the Night” by Beryl Markham for the twelfth time in her life, as it was her favorite book of all time. I glanced over to see the book on the opposite nightstand, sitting opened with a bookmark wedged between the worn pages.

It was then that I caught the bookcase near the window in the afternoon’s fading light, it’s shelves filled haphazardly with novels. I gasped when I realized that the bottom two shelves had neatly ordered Moleskine journals. I realized her carefully protected history was there for the taking, to be read at my leisure.

It was into the second month of reading that I came across a journal unlike all the others. Lot 24: La Mort d’Arlequin 1905, read the top line. Picasso, Rose period, gouache and pencil on board, 68.5 x 96cm, all were penned on subsequent lines. Mid-page were two slightly arched slash marks separating each page into two sections. “Question of death, State of waiting” were written towards the bottom of the page in a broad and flourished style. There were 34 complete pages, with a final paged signed “To lose one’s art is to lose one’s soul, Bruce Chatwin”. It did not take long to uncover that the celebrated author Chatwin had worked at Sotheby’s in the spring of 1962 and was one of 2 specialists employed to catalogue the collection of British novelist William Somerset Maugham, who had put them up for sale. Chatwin had kept two “sets of books”, the official Sotheby catalogue and his own musings about each piece. He had gifted his personal notes to Maugham upon the completion of the sale.

Several journals later I found the note of my grandmother’s visit to Maugham’s villa overlooking the Mediterranean where the 34 extraordinary works of art had last congregated together. She had traveled there with Lord Beaverbrook, one last time shortly before his death. When Maugham observed her writing in her journal, he offered her the Chatwin small black notebook with an off handed comment about life’s journey of loses and what we so easily squander, all to be recorded with one’s own pen.

When Sotheby’s learned of the existence of the Chatwin notebook and it’s providence, they offered $20,000 which I accepted in order to finance the remaining months devoted to reading my grandmother’s story. Her journey, my fathers and my own are ripe to be told, another day.

About the Creator

Joann Amoroso

A mother of triplets, born and raised in Montana. A business woman and a writer from an early age.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.