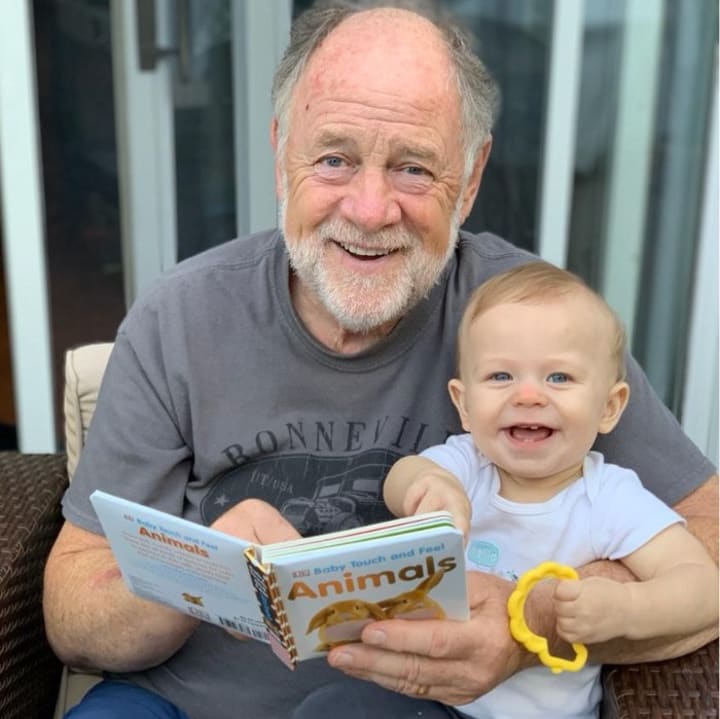

About me--Harry Hogg

I began life under a bush in Gant's Hill, Essex.

My life began beneath a shrub on a roundabout in Gants Hill, Essex, U.K. (No, I’m not Moses!) I was found by a young couple leaving the Odeon cinema having spent their evening watching a Spencer Tracy movie, Edward, My Son.

With no parents claiming me, I was put up for adoption, and subsequently placed at a Dr. Barnardo’s Red House Orphanage, Ripon, in the west riding of Yorkshire. I was two years old.

At 5 years old, I had not yet been adopted. (Go figure, right?) Barnardo’s mandate at that time was to care for orphaned children aged 2–5 years. Okay, clearly I was not an adoptable child. I’m still grateful Barnardo’s didn’t put me back out on the streets. I remained at the orphanage until adopted, (finally) at 8 years old, the oldest of 27 children. I had earned the reputation of being a problem child. (I don’t know if that’s true, but its a good line😁)

Naturally, my recollections of the orphanage don’t start until I was 6 years old. Grace, the house mother was, responsible for eight children. We were looked after in a large family room with a kitchenette attached, and a large bedroom on the second floor with cots and beds.

Over half a century, I’ve heard terrible stories about orphanage life. Red House was the place where I learned about love, to the extent any 6-year-old child knows what love is.

The problem with over staying my welcome at Barnardo’s, being outside the age charter, I was given a share of the work. There were other boys with the same house mother, though names have deserted me. They were younger, of course. Some stayed six months, others two years, one by one they left and I didn’t. After breakfast, Grace walked me to the bathroom, insisted on watching me clean my teeth, wash my ears, and brush hair. Then made me stand guard over children 4–5 and do the same. Before leaving the house, I’d get a hug from Grace, put on the bus to school, and head off to do battle. The school was never fun. Never.

Memories, broken, splintered, are those of something that once was, having been flung far off into space. Fragments, having survived, return from my childhood, hurtling back to speak of warmth, or friendship, or what goes with what…the fork goes on the left side, Grace said.

In the grounds was an oak tree. I skinned my knees a hundred times, and from its branches, collected pockets full of acorns. It was felled by a bolt of lightning when I was eight. I saw it, I did. No kidding. It was felled by a bolt of lightning when I was eight. I saw it happen from the dormitory window on a stormy night. I wouldn’t come out from under the covers for two days, (oops, little more exaggeration).

The orphanage was a mansion of corridors, sweeping staircases, and chandeliers. Fun was had sliding down the banister, but only if Grace, holding a mop, didn’t catch me. She never did catch me; she never meant to. She laughed and when no-one was looking danced with the mop handle. (That’s true!)

A truly poignant memory is that of a particular odor. It was a clean smell. On days when this clean smell was at its most potent, it lingered in the corridors, squeezed under dormitory doors, and was scary because every time the smell came a child from the orphanage disappeared. That is an absolute fact. Supported by the empty chair at the supper table. I’d never see that kid again. I didn’t know why. Nor could I ask, Grace said.

Mr. Bunsen, the silvered hair caretaker had huge craggy hands and a gimpy walk. I was out playing in my space explorer outfit, the one I’d received from the man and lady who came to see me on weekends. Mr. Bunsen was mowing the lawns when the clean-smelling man approached me. I didn’t get a whiff. The fresh cut grass disguised his approach. Here, he said, in a soft voice, let me fix that for you. My space helmet fitting badly.

He took my hand and walked me to Matron’s office. She was smiling when we entered the office and greeted me with open arms, beckoning me around the desk. Grace was sat beside her. There were tears in Grace’s eyes. She hugged me hard. The clean-smelling man dragged a chair from the back wall to the desk. He sat with his hands on his lap and spoke to me in quiet tones. He talked of the two people who had been coming to see me. They were friendly. They brought me chocolate, took me to the zoo, the cinema, and a train to London and Madame Tussauds. It was the first time I ever slept away from home. We stayed in a hotel near Buckingham Palace. They told me the Queen lived there. There were men in enormous furry hats. The man told me to call the woman Marion and him, Frank.

The lady was graceful, with smiling eyes, and wearing a red beret on the back of her head. On the lapel of her cream jacket, she wore a corsage of fruits. Frank was the biggest man I’d ever seen. He talked of the sea, catching fish from a boat. He told me lots of stories, scared me, excited me, and gave me a boat he’d made from matchsticks. I’d only ever seen photos of the sea.

Releasing me from her arms, Grace pulled me back and kissed me on the forehead. A strange kiss, longer than her nightly kiss goodnight. The clean-smelling man called me to his knee. He put his hands on my shoulders, and then with one hand, lifted my chin. How would you like to call these people your parents? He asked. Grace dabbed a handkerchief to her eyes.

The orphanage was more than a home; it was where I rode my childhood dreams, which was as far as any child could ride, coming home to find Grace waiting to change me out of my school clothes, unaware I’d ridden off to war that day. To whom does a kid explain such magical sophistries?

For eight years, I had lived in a secret world. A place where at night my bed became a ship. Where I got kissed and tucked in tight. A child born in a whirlwind of misunderstanding and hurt. Damned by the rainbow, I rode wooden dolphins until muddied with affection.

In my mind, my parents were solid as gold. I grew up with never a thought of anything going wrong with their marriage. That was a child’s belief. As an adult, I learned they had tough times; it is never the way a child imagines. Mum had soft, loose, wavy hair, eyes that spoke for her when her voice was quiet. I was a tough kid, terrible tantrums, divulging into floods of tears if I never got my way in everything. Mum held a troublesome child safe and never let go, even when dealing with spitting verbal abuse. She made a world that held me spellbound.

At ten years old, I was no longer broken. A child still, yes, sighing harmonica notes without the endless need to cry.

My new home had a red flagstone kitchen floor, cool on my feet, scattered with handmade rugs, those woven by mother. The rugs appeared less red when came the daylight. I don’t know why I remember it that way.

I loved early mornings, having a cup of tea with dad at 5:00 am, listening to the shipping forecast on his old battery-powered radio. There’s nothing that compares with the tone of that old valve radio. The words in the forecast sounded like poetry to me, the same poetry that my father loved, Bailey, Rockall, Shannon, Fastnet or Forties, Dogger, Malin, and German Bight. Descriptions, dad told me, were weather zones. He paid special attention to the areas: Malin, Rockall, Faeroes, and the Hebrides. In such zones, he spent days trawling for cod.

Talla Rainbow, was the name of our home in the shadow of Ben More, and today is the better part of two hundred and fifty years old. My great-great-grandfather, a crofter, built the original.

Today, when I come home to the shadow of Ben More, to the cottage, I’m reminded of the first day I came to the island. The rocky terrain, the cottage, and the kitchen haven’t changed in sixty-two years.

These memories are like water bumping through the lead pipes of my brain. I remember the fragrance of Swan Vesta matches being struck, hearing the boom of exploding gas igniting a blue flame. More than a room, the kitchen is where I recall mum spending most of her day. It was the heart of my family’s existence, evoking memories of childhood. The copper kettle sitting on the cream and black Aga. Its battered swan-neck spout and buckled lid — the same kettle that sat on the stove the first day I arrived.

Come the wintry days, mum offered a blanket for visitors' knees to enjoy the warmth of the Aga while she made pancakes. Mum said there are as many ways to make pancakes as there are to making friendships. She made them thick, adding fresh berries and syrup. The cottage was kept spotless, bare, and some might say dismal — the furniture, now antique, well-polished, practical.

Visitors today, as rare as they are, comment on the whimsical Victorian style. To me, after sixty years, it feels normal.

The island encourages a feeling of serenity, but nowhere more than in my study. It’s a room filled with enormous furniture, bookcases, a desk, lamps, and old photos. On its pale-yellow walls, Margaret Tarrant prints, once hung in my boyhood bedroom, have been moved to my study to enhance my feeling of security.

It was there, sitting at my desk with a laptop, I learned to breathe. From that breathing came life. I have no grand ideas that I’m a talented writer, let alone chase the idea of greatness; I am a storyteller. But I know when I stand on Scottish soil; there is poetry hanging in the Celtic air.

In old age, it isn’t unusual to spend hours walking the shorelines, jagged and unforgiving: others sandy, and regain that long-ago feeling of dad walking with me along the water’s edge.

In my youth I climbed Ben More to free myself from the island’s capture and enjoy the elation of looking toward the mainland. Oft times, catching sight of a yacht tacking hard, fighting the wind mid-sound. I’d wave as a city kid might wave at trains.

To talk of the mountain, its craggy face, wet and shadowy, is to have people understand it is a living thing, a protector, a guardian, a constant, like a parent. It has good days and sad, one day gentle, the following severe. So it is with the mountain, letting you go but calling you home.

As a trawlerman, dad lived a tough existence. He was a poet. Not a romanticist or romantic. He worked with the perils offered by one of nature’s wildest and unpredictable children. He was a man beaten, shaped, and inspired by the sea.

Beneath the east-facing window of my study is an aged Smith-Corona. It belonged to dad. I still hear the clickety-clack of letters punched out, making poems. I imagine those he had yet to write — a thought which keeps him within an inch of my heart.

Sometimes I feel a million miles from Ben More’s shadow — from my youth. I return home as an old man to listen to the snow falling, protected from the storms of life. Listen to the screech of the gulls, sniff the lobster pots, and taste the salt air cleaning my throat. Entwined in the fog’s mystery, we island people live with respect, passion, and unafraid of hard work.

Sometimes hurting, when tears came without notice, I found my way home. Or remembering how the hills looked against the coastline, wanting the coolness of the water around my ankles.

Leaving childhood, the kitchen, beyond youth, beyond Paris, there were no more homemade pancakes. No clatter of the Smith Corona’s keys, no heat next to the Aga. I seldom receive friends, but when I do, I make tea.

It’s hard to know when I became a dutiful son. Mum, in later life, found comfort in the sherry bottle come the evening. Dad watched the nine o’clock news on BBC with a cup of tea and a digestive biscuit. On my last visit home, before mum died, I arrived home at ten in the evening. She was in bed and wanted to get up, but I refused to let her. She was eighty-seven. I held her hand and told her made-up stories of pebbles, sand, and seaweed. She loved it whenever I talked to her about the sea. Dad and I spoke before he went to bed. He showered, put on his PJs, and retired to their room. In that short time, mum had gone. Dad stayed with her body that night, never coming to tell me or bring me to her. It was his time.

Two years later, in 2012, dad died and was then given to the island waters, following his lifelong friend, Snowy McLeod. They are where they belong. Before his burial, I had time with dad, though I didn’t touch him — this man had been everything to me.

In life, there are super achievers, at least to the extent that they excelled throughout their careers. After winning my R.A.F. wings, I graduated in the top ten percent of the class, and it was this achievement earned me an application to join strike command as a candidate for advanced flight school. I was also a man born of rape, incestuous rape. I had no God-given right to be alive. I felt a new sensation in my body. I’d not thought it before. It became my career, spending hundreds of hours practicing techniques in a controlled environment. Developing the confidence and skills to hover a Sea Harrier VTOL over a moving deck of an aircraft carrier. When the day came. When everything practiced is put to the test, sensations ignited in every nerve end of my body.

Whatever success is, it was men of the sea who taught me how best to get through life. When I left the island, it well equipped me to deal with everything but loss. I had learned the language, it was a harsh language, loose and harsh, but it was a language built on nature’s anger and not a little poverty. Trawlermen will tell you there are only two ways of gaining riches: one is finding it in oneself over wealth or increasing your possessions by decreasing someone else’s. I grew up among people who, and this is the truth, did not concern themselves with wealth but with life’s riches. There is a difference. The richness of life, involving hard work, fierce manual labor, cannot compare to a man who might have sold well on the stock market. Wealth may divide their lifestyles, but the richness of life separates them as men. I was never a trawlerman at heart. My father knew that. I had a softness that let me down, an ache for romance that every trawlerman scoffed at, yet I loved those men fiercely.

I became a leader of men accidentally. Such an accident, well, it taught me the single most important thing about leadership. Humility. There is no way to talk about humility and appear humble. Leadership is not about a title — the title is part of the accident.

I was an airman first, later managing a music company, then an entrepreneur. That all changed when I became a Greenpeace activist. I had skipped over the usual first levels of leadership where I thought one were supposed to essentially learn how to manage people and landed as a director. I don’t necessarily recommend this; it was terrifying, I still remember the first time one of my teams turned to me and said, “well, you’re the director now, what do we do about it?” It also meant that I thought about leadership differently than those who join the ranks of influence through the usual channels.

Today, with my body falling apart, I continue to dream the same dream. When I sail into Tobermory Harbor with Paladin, white water from the bow, I see him, this enormous man, waving. Seagulls appear from everywhere at once, hundreds and hundreds of them. Dad steps ashore and hugs me as if I were still his eight-year-old son. The smell of him is intoxicating, his rubbery, salt burned body, seabirds exploding with excitement behind him. I sail into harbor and close my eyes and know I’m home.

I’m a sailing man, in my heart and soul. That’s just it. I mean, really, there’s nothing to add.

Some morning risings have been exquisite of late, each one a seeming dress rehearsal for the next. I write a lot when out sailing, it seems like a gigantic task to finish my book. I slept three hours, till 11.pm., woken by a passing Grey whale, with calf, breaking the surface and (disguising themselves as a steam train) the sound of breath spraying silver in the moonlight. I wanted to feel that wetness on my face, but too soon, they swiftly swam out of sight.

I stayed naked most of the day.

Writing came late, maybe too early. I’ve studied the false ego of the writer, swept away a million skeletons, exhausted myself on the great ocean of life, and concluded that the first task of a man who wants to be a poet is to study his own awareness of himself. A Poet I am not. What can be learned from books is second to natural development. No one is born a visionary, only a long journey through all the forms of love, of suffering, and perhaps, too, madness.

A poet, then, must first be destroyed to become whole.

Things are different now. Writing every day has changed all that. Very often, I’m forced to scavenge for the right idea to connect or complement what I’ve written. I’ve come upon poems, or a piece of prose long forgotten, buried in the back of a paperback or a sailing log. I like to work at it again. It’s seldom better.

Some lines could have been written yesterday because they seem to reflect something that only started happening to me a few days ago. Flashbacks are not so scary, but flash-forwards are a wonder. This past week I investigated the face of the vast ocean and saw myself exactly as I was thirty some odd years ago, just as I’d predicted, failing to meet love’s every new tide.

These are heady days for me. I’m doing what I like — sailing, horse-riding, writing a bit and working on some songs. There are rough days, too, but nothing I can’t handle. My battle with time has not been helped by seeing myself as I was 30 years ago. Funny, there was never time enough then either.

I am one of life’s fortunate people, and one day, if not too late, I’ll appreciate that. I’ve been a squatter, sometimes a gypsy, content anywhere, a long-time wanderer who spent much of my life rootless, not collected at birth — but since collected. I became adept at conjuring people’s love for me, carrying only what I wanted, or supposed, from place to place.

The first half of life is spent acquiring possessions, the second, getting rid of them. I started on both journeys late.

In my head and heart, I am building a barn. Big, redwood, huge enough to hold my lifetime. I’ll build it. I will. It’s the last big dream [until the next one] and I’ll make it happen. A barn. Imagine. Three stories high with lofts to store all my dreams, my memories, my promises, and my maybe’s, my hopes, some yet to be recognized, and of course, my dogs and cats.

It won’t be a castle. I learned that lesson, saw it dissolve, become dust again. No, it will be a barn, rugged as hell, a place I can get through the day, and where the night won’t make me nervous. The night does make me nervous. Not for any reason, except maybe that it catches me unaware and follows me the way a woman does when she wants something.

I waited through the ruins, maybe for a face — kind, fresh, encircled by a halo of cascading hair; a face, the beauty of it passing without a hello spoken would break my heart, stop my breath. Jenny stopped.

I know that life hangs on, but only long enough to get through the day’s lies. So, it is important my words stay largely private, unrecognized, except by those for whom, with age, truth has become a way of reconciliation.

Life, I must say, could not be better.

Thank you for the compliment you pay me in reading.

About the Creator

harry hogg

My life began beneath a shrub on a roundabout in Gants Hill, Essex, U.K. (No, I’m not Moses!) I was found by a young couple leaving the Odeon cinema having spent their evening watching a Spencer Tracy movie.

The rest, as they say, is history

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.