Kicking and screaming, I fought with all of my strength—all the physical strength of a 4-year-old child—to stop from being put into the car. I was like a wild animal, and to be back inside that car meant that I wouldn’t be able to see my dad again, at least for another week, and that felt like an eternity. I don’t remember the unfortunate person who was tasked with carrying me—perhaps it was my uncle—but the tears blurred my vision and the gut-wrenching, profound despondency that only a child could feel within the storms of a tantrum clouded my memory. All I wanted was to be with my dad; at the time, I could not be. It was a matter of scheduling and lack of supervision, and such issues were trivial to a child. Then, I didn’t know that at this moment I had broken my dad’s heart. Soon after, he would make sacrifices in his daily life and work schedule, just to remove this source of pain from my reality.

For my dad growing up, he was not afforded the same luxury from his parents. He was the youngest in a family of 5, born in Kampong Cham, Cambodia. His mother died when he was 2 years old, when he was far too young to have formed any vivid memories of her—not of her face, her touch, nor her warmth. His sister served as his main parental figure during his childhood, because his father was mostly absent too. It was through this pain that as a young man, my dad vowed to be there for his own children when it came time for him to have his own.

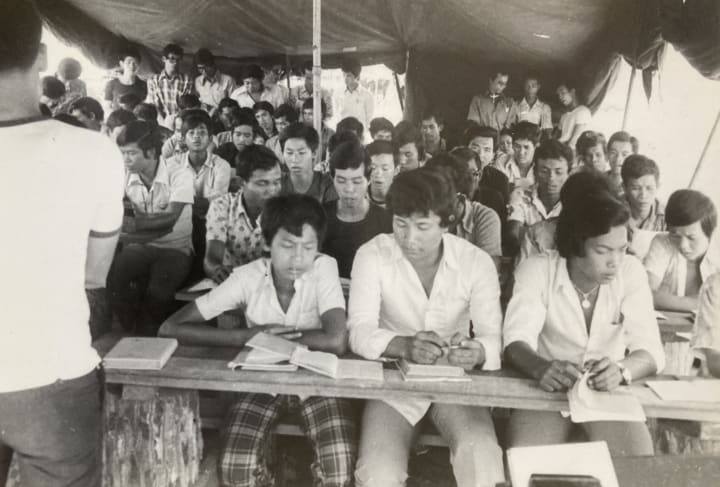

When he was in his twenties, Cambodia was a fractious country fueled by political dissonance and discrimination against ethnic minorities. My dad was attending Phnom Pehn University when the capital of Cambodia fell to the Khmer Rouge, a rural communist guerrilla movement, in April 1975. The Khmer Rouge evacuated the entire city under the guise of an impending American bombing raid. Among 2.5 million people, he was herded out of the city and into the countryside. Emptying the cities of Cambodia and sending the urban population to work on collective farms was part of the regime’s belief in a self-sufficient agrarian socialist society, in which they preached that “planting rice and digging holes would make the country great again,” described my dad. Along the way, 20,000 people died on the march. It would take over 3 weeks until my dad would make it to his hometown, which was now controlled by the Khmer Rouge.

My dad worked in the rice fields of Kampong Cham without pay, since the currency was abolished under the belief that money would lead to corruption. He was given clothing, rations, and housing. Every day and night he would plant and break rice and then fall asleep in fatigue. He had never planted rice before; thus, these tasks were exceptionally taxing. Such a predicament was common for the displaced urban civilian, who now faced discrimination for being coddled by the city. If one wasn’t killed for being associated with the previous government, military, or as an intellectual, the long shifts in the rice fields and lack of agricultural ability of the former metropolitans led to death from exhaustion and starvation. To the Khmer Rouge, this didn’t matter, as the bodies were left in the rice fields and repurposed as fertilizer.

Leave now or be killed. This was a warning from an insider to my dad’s oldest brother and classmate, for the two were associated with the former military. My dad fled with them in the night, and at that moment, he knew that there was no turning back. Carrying only a backpack with rice, a few military rations, and a small vial of poison made from the crushed seeds of a toxic fruit—as a last option for if they were caught or when the voyage would become too much—their goal was to flee northeast to the border of Thailand. It was a treacherous journey that was mostly done once the sun was down, for fear of being spotted and captured by the Khmer Rouge.

There were many close encounters with the Khmer Rouge too, and my dad found himself hiding not more than a foot away from a soldier or sometimes even making direct eye contact. Somehow, he always evaded death in this way, even when wandering through minefields became a common practice. Soon, food and water became scarce as it was too dangerous for the 3 men to go into the villages to get food. My dad would resort to digging for roots to eat, picking whatever fruit that he knew was edible after watching birds peck at it, and boiling water that had pooled inside muddy buffalo tracks.

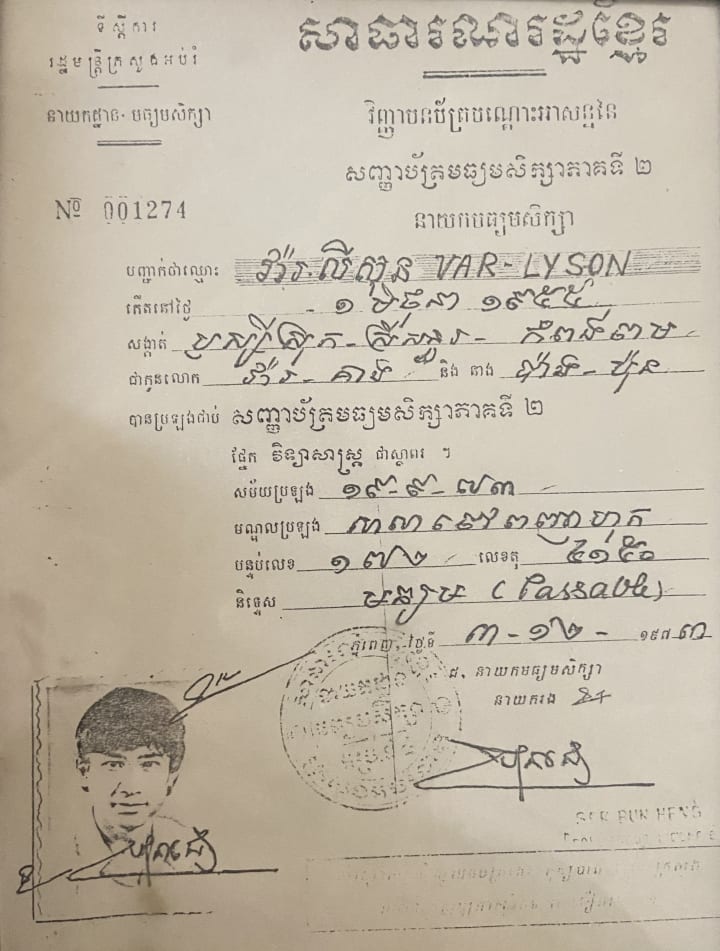

After at least a month-long trek, he could barely find the strength to walk. Eventually, the 3 men crossed the border and into Thailand. After being mistaken for Khmer Rouge, having an ax on his neck, and then thrown into jail for 3 months for not having a passport, my dad, his brother, and his friend would make it to a refugee camp in Surin and wait for sponsorship to be able to leave for another country.

After a few more months, my dad received the fateful call that the U.S. was accepting refugees. While he was in Surin, he had aspirations of one day going to California, having a tile roof house, and daughters. In August 1976, without a penny but 2 shirts, a gifted pair of pants, a set of flip-flops, my dad landed in Brownfield, CA.

In San Diego, he would clean buildings and wash dishes until he got a sponsor. He would then spend every day working as an instructional aid for refugees and attend school at night to learn English. Eventually, he would make his way to become an electrical engineer, get married, and have two daughters—the youngest one was me—and a tile roof house. But family life would be complicated. In my childhood, my mother exhibited symptoms of depression and psychosis, which disabled her from working. She would spend most weeks with my grandparents and largely would be absent in my life. My sister was old enough to attend before and after school programs while my dad was away at work, but I was too young and had to stay with my mom during the week.

Most days I felt lonely and would lock myself in the bathroom and cry. During the brief weekends when I was able to see my dad, I would be so elated to spend time with him; however, he could see my sadness whenever we said goodbye. After witnessing me cry and kick at the car when I didn’t want to leave, my dad made another vow to find a solution to allow me to stay with him and my sister. He arranged with his employers to have him work nights instead so that I would never be left alone with anyone but my older sister. I attended kindergarten at an earlier age than average, and my dad would always be around to pick me up from school before he headed to work. Without fail, he would always have a home cooked meal prepared for us to heat up for dinner without him, and every night when he came home, he would check on my sister and me before going to bed himself. I knew he was exhausted, but he always put in everything he could to hold the family together. Every so often, he would find time to set aside for my sister and me to have memorable experiences like camping, visiting amusement parks, and different cities. He did everything for us.

Cambodia eventually reopened in 1989. Despite the encouragement of his friends and his own desires, my dad has not returned to visit his homeland since the fateful day he left for the U.S. He was always too busy taking care of his family, for it was his children that brought him the most joy. No matter how overworked and wearied he was, he dutifully kept his promise of being there for us. I’m really not sure how he did it, but despite the pain and suffering that he endured throughout his tumultuous life, he did everything he could to lessen mine. Now that both my sister and I are older, we plan to visit Cambodia as a family this coming year. I know that will bring him so much joy, to be able to be back in his homeland with his children by his side.

About the Creator

S.R. Var

I wrote to understand the world around me. I stopped to become a scientist. Decades later, I write to understand myself. Perhaps if you see a bit of yourself in my writing, it may bring you some solace too.

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insight

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Comments (1)

Thank you for sharing this. What a man and what a life!