INTRODUCTION

The devil is in the details. An apt description for a movie about a serial killer who targets according to the seven deadly sins, but also an important notion about the nature of quality storytelling, especially when it comes to mysteries. A solution that comes out of nowhere or isn’t built up properly won’t be a satisfying conclusion and can leave an audience frustrated with the film. Therefore, planting clues and hints to the ending can help create suspense as well as intrigue.

By analyzing the first ten pages, the audience can better understand how the beginning of this emotional and mental journey affects its chief characters. Or rather, doesn’t affect them, as these pages contain several examples of visual storytelling, clever dialogue, and subtle character choices that persist throughout the story, and consequently lead to the iconic climactic reveal.

SYNOPSIS

Detective William Somerset is retiring in one week because he no longer understands the world and its cruelty. His hot-headed replacement, David Mills, is eager to get started. When the two of them are called to a crime scene for an obese man who had literally eaten himself to death, Somerset tries to get out of it, insisting it’s the start of something sinister. Mills gets assigned to a new victim: a lawyer who had a pound of flesh removed from his body and the word “GREED” written on the carpet. Somerset revisits the previous victim and finds the word “GLUTTONY” written in grease behind the fridge.

Somerset tells Mills and the Captain that the two murders are connected to the Seven Deadly Sins and are likely to see five more victims. Though hesitant to join, Somerset offers Mills some insight after they have dinner with Mills’ wife Tracy. The duo finds a clue that leads them to the lawyer’s wife, where they learn that a painting in the lawyer’s office is upside down. Returning to that crime scene, they find a series of fingerprints that belong to a former felon. Assuming him to be the killer, they try to go arrest him, only to find his desiccated husk and the word “SLOTH,” revealing he is not the killer, but another victim.

Somerset meets with Tracy, who tells him that she hates this city and reveals that she’s pregnant. Concerned with bringing life into this crazy world, she asks him for advice. Somerset reveals that he was almost a dad, but struggled with the decision as well and admits to making the wrong one. He tells her that if she does keep it, spoil it every chance she gets, but if not, she should never tell Mills.

Later, while deliberating on the case, Mills gives Somerset some inspiration to use an FBI contact and track down a potential lead: Johnathan Doe. Upon arriving at his door, the pair are shot at, and they chase after him. Mills is injured and cornered by John, who has a gun to his head. He spares Mills and runs off before Somerset can catch him. When the duo forces their way into the apartment, they find a religious shrine and notebooks detailing the killer’s thoughts. John calls them and says that he’s moving up the schedule. Over the next couple days, two more victims pop up: a model who was mutilated and committed suicide rather than be beautiful (“PRIDE”); and a prostitute who was killed by a man (forced at gunpoint) wearing a knife-bearing BDSM outfit (“LUST”).

As Sunday arrives, John Doe arrives at the precinct, covered in blood, turning himself in. Consulting with his own lawyer, he forces Somerset and Mills to take part in a deal where he will take them to the two remaining bodies out in the desert. During the car ride over, John expresses his frustrations at the world around him and the sin he sees on every street corner. Mills antagonizes him, insisting that he’s nothing and will be forgotten in a week. Upon arriving at the location, they find it deserted. They start walking John out into the field until a delivery truck appears down the road. Somerset leaves Mills guarding John to go investigate. During this absence, John starts to goad Mills.

Somerset opens the delivered package and is horrified by its contents. He races back to Mills, who is being told by John that he visited his wife. As Somerset returns, John reveals that he is envious of Mills’ ordinary life, making him the sin of “ENVY.” As a result, he killed Tracy to encourage Mills to kill him, thereby casting Mills as “WRATH.” Despite logic and reason, Mills snaps and murders John, allowing the serial killer to win.

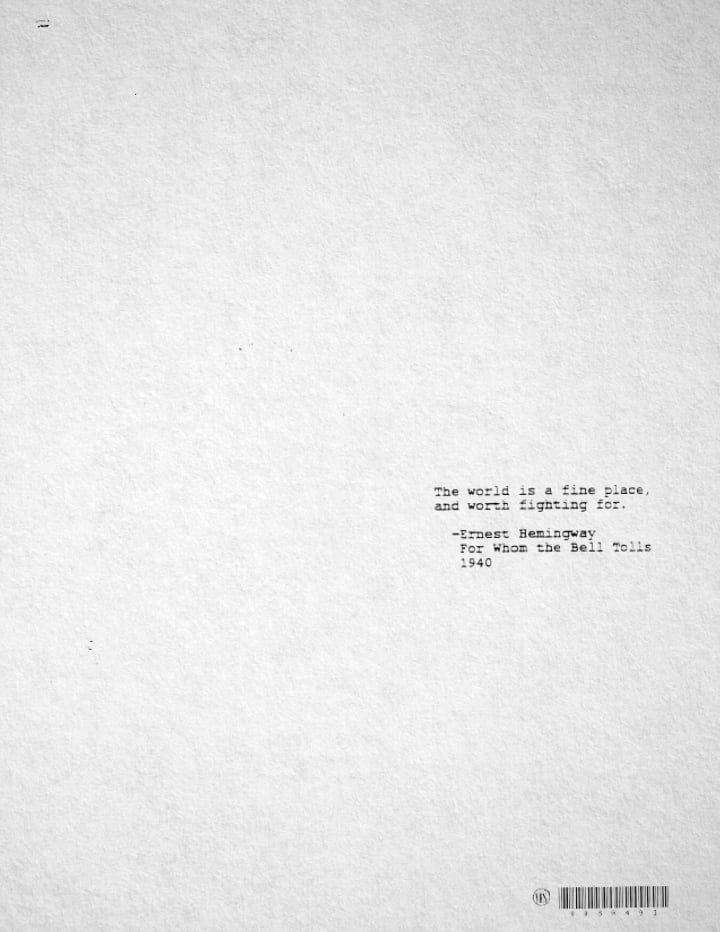

Mills is arrested and Somerset tells his captain that he’ll be sticking around for a while, citing the Ernest Hemingway from For Whom the Bell Tolls:

“The world is a fine place and worth fighting for.”

Though the film closes with this quote, the script shows it appearing on a separate sheet before the First Ten Pages.

PAGE ZERO

The novel in question, to over-simplify, is about an optimistic guerrilla fighter attempting to overthrow a fascist government, and his struggle to make a difference or find meaning in the war efforts.

This quote does appear in the final film, but only at the end, with Somerset providing an additional line: “I agree with the second part.” [The world is… worth fighting for]. Throughout the film, we’ll get a lot of evidence that Somerset is weary of his job and the world around him. Part of the reason that he’s retiring is that he no longer feels like he’s making a difference or, rather, that there is little to no point to him doing so. This apathy is Somerset’s fatal flaw; the major thing that requires fixing in his life.

Therefore, the quote is inferring the theme of the film and the major arc that Somerset will go through.

This quote is like one said by the character Samwise Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002):

“There’s some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for.”

Though the hobbit’s line is likely a reference or paraphrasing of Hemingway’s original quote, it does offer up a unique comparison in terms of tone.

Optimism is something that is increasingly hard to come by, and that the population’s doubt about the efficacy of many of the world’s systems (political, educational, economical, et cetera) is exponentially rising. Pessimism, nihilism, and apathy are, therefore, also on the rise. Sam’s belief that the world is worth fighting for is all about his optimism and his desire to do good, which is a noble ideal. However, he is in a fantasy setting, akin to a fairy tale, most of which tend to be more upbeat and follow a certain rhythm such as good always triumphs over evil. It’s much easier to have optimism in a story that follows such a formula.

But not in Se7en.

Here, Somerset’s world is dark and chaotic. He’s a Detective Lieutenant who’s been with the service for too long, having seen and/or dealt with the darkest sides of humanity. Very much like the source from which Hemingway’s quote originates, Somerset’s world is anything but a fairy tale. Thus, it’s much harder to stay upbeat and optimistic and fall into feelings of apathy.

From this, it can be concluded that this quote is meant to set the tone of the screenplay by telling its reader that the movie is going to play on themes of determinism and optimism in the face of overwhelming chaos and darkness.

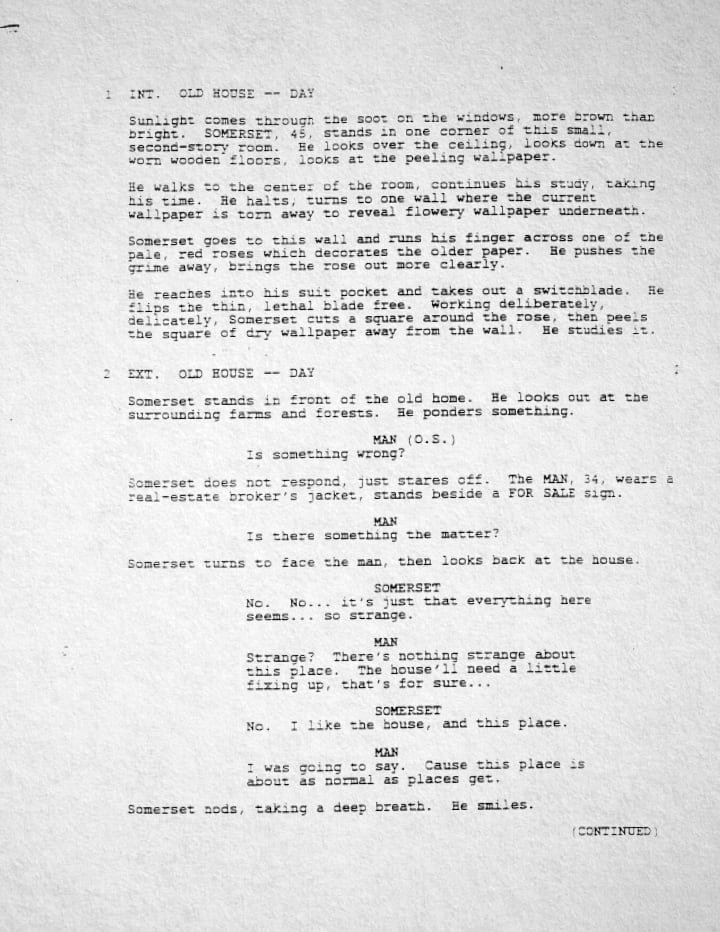

PAGE ONE

The very first image that the screenplay shows sunlight coming through soot-covered windows and casting a “more brown than bright” shine on the room. Right away, it establishes that even though sunlight (which is usually a metaphor for hope, positivity, and warmth) is breaking through, it’s not shining brightly enough to remove the darkness from the room.

The paragraph continues to describe the room as the protagonist, Somerset looks around. His apartment is not in the best shape, with worn floors and peeling wallpaper. This provides more evidence into Somerset’s tragic flaw: he’s not taking care of his apartment anymore. Later, the script will say that he felt so beat down by the world around him that he’s trying to leave it all behind.

Somerset then walks around his room and notices the wallpaper beneath what’s currently peeling. Roses. This is likely symbolizing him having covered up his own happiness with his apathy. This will be expanded on later when he reveals he wore down his wife during pregnancy to prevent bringing a child into their crazy world.

Absent from the final film is Somerset removing a piece of the rose wallpaper and carrying it with him throughout the case. This scrap of wallpaper will be accidentally shown to Tracy and Somerset will call it “his future.” However, after John Doe is murdered, he tears it up as a symbol of succumbing fully to his apathy and giving up on any remaining thoughts of happiness and saying, “this is where I belong.”

The next scene shows Somerset with a Realtor standing in front of a house in the country. This immediately tells the audience that Somerset is looking to move away from his apartment and leave his old life behind. His age is given as forty-five in the script (Morgan Freeman was fifty-eight when the film came out), so it can be assumed that he’s retiring.

Somerset calls the area “strange,” calling attention to the fact that it seems so serene and peaceful. The Realtor calls it normal, which Somerset confirms (on Page 2) is exactly what he means.

In just these first two scenes, it can be inferred that this movie is a story about Somerset wanting to move to the country and begin a normal life, hoping to be free of his apathy. Instead, it is solidified as he is dragged back into his “normal” life.

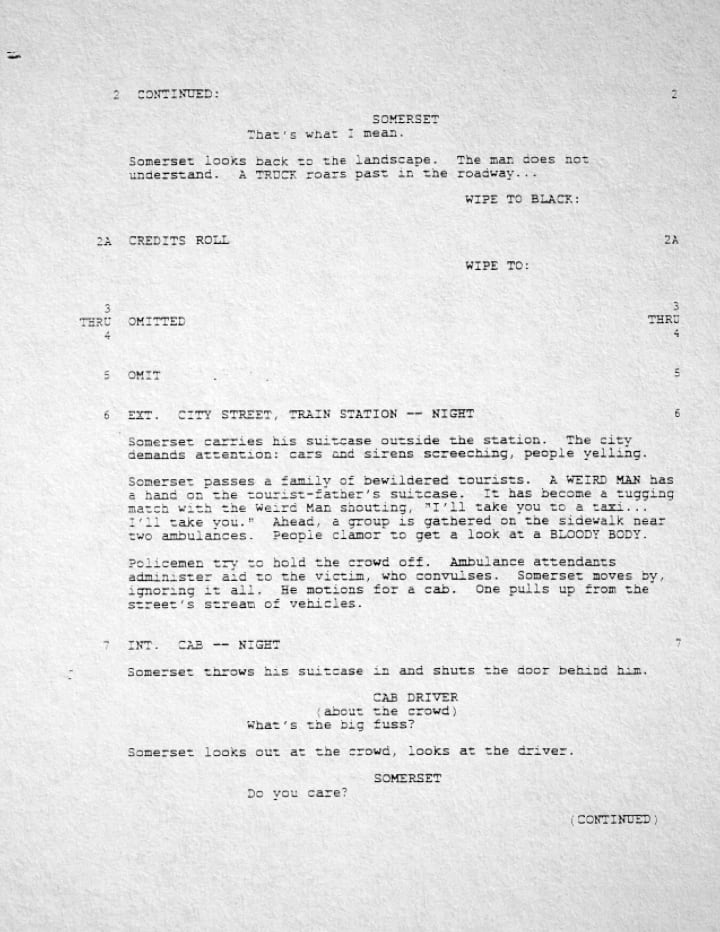

PAGE TWO

Contrasting the serenity of the “normal” country house and complimenting the derelict nature of his apartment, the script returns Somerset to the city. As he walks around, he sees a family of tourists getting either robbed or accosted by a weird man. Walking further, he sees a group of people rubbernecking a bloodied body, while the officers on the scene try to hold them back and paramedics attempt to help.

Somerset ignores these events and summons a cab, showcasing his apathy, almost to the point of being unlikeable. Once in the cab, his Cabbie inquire about the mob prompting Somerset outright asks him: “Do you care?”

The reader is being shown, visually, that the ordinary world around Somerset is not a pretty picture. It had been inferred with his apartment but is now being displayed clearly for the reader to witness. Prolonged exposure to a toxic environment can create toxic behaviors in otherwise righteous individuals and Somerset is no different.

If everything is chaos, eventually it becomes the norm.

PAGE THREE

The cabbie is less than appreciative of Somerset’s accusation of his own apathy. He retorts with “Well, excuse me all to Hell.” This is an excellent example of showing that Somerset’s mentality is wrong, with someone immediately finding the notion of apathy offensive. The use of Hell within the line, though, could be construed as foreshadowing Somerset’s coming adversary.

Giving Somerset more reason to be pessimistic, the circle of onlookers expands to reveal a fight happening between two people. The police fail to stop it, perhaps foreshadowing that Somerset and Mills will be unable to beat John Doe, or even stop his seven-person murder spree.

After the cabbie asks Somerset where he wants to go, Somerset replies with: “far away from here.” This line cements his motivations and his goals: he wants to leave this place and never come back. He wants to go away from the chaos, from the darkness, and away from his lack of understanding of this world.

As if to act as a metaphor for being dragged back in, the script takes Somerset back to his apartment at night, with a car alarm blaring. The reveal here is the presence of moving boxes, further asserting that he’s getting ready to leave everything behind. He also has a large bookshelf with hundreds of books. This is good visual shorthand to imply Somerset’s intelligence, something that he will discover he shares with John Doe (and his bookshelf) and contrasts with against Mills, who requires Cliff’s Notes to understand the biblical and educated meanings behind the crimes.

Somerset turns on a metronome and uses it to drown out the car alarm and fall asleep. This whole scene takes up half the page, and takes several beats to achieve, thereby implying how long it truly takes him to succeed. The metronome is a constant ticking sound, back and forth in its repetition. Somerset using it to focus on himself shows that he is using the metronome as an anchoring point: a constant source of order in an otherwise chaotic world. His ability to sleep to the metronome is an extension of his desire to return to a normal life and find order in a world of chaos.

PAGE FOUR

A title card shows the reader the first of a seven-day timeline over which the events of the rest of the film take place. Appropriately, for a movie that deals with religious overtones and symbolism, it begins on a Sunday. Somerset is busy getting ready for the last week of his work by straightening out his shirt and tying his tie. His bed is neatly made and he even brushes dust off his jacket. For someone who doesn’t care about the outside world, he seems to care about his own appearance.

There are several key things the reader has learned about Somerset as of this page. He uses the metronome to fall asleep, he is moving from the city to the country, he doesn’t care about the plight of his fellow person, and despite his apartment being derelict and in the process of moving, he makes sure that he is neat and tidy before heading out. These actions all signify that Somerset is trying to take control in a world of chaos.

But for all that has been learned, a few questions arise regarding his backstory: “why is he like this? What has driven him to this level of apathy? Why is he trying to leave?”

These questions can be simply answered in the next paragraph, when he picks up some items, which include a gold homicide badge. Somerset is a detective. Using the evidence at hand, it’s easy to deduce the answers to the questions posed: Homicide is no picnic in terms of job satisfaction; they deal with horrifying scenarios, hysterical loved ones, and (sometimes but not always) psychopathic individuals, not to mention the unsolved cases that can nag at them. This would take a toll on anyone in a short amount of time (as we see by the end of the film), but Somerset has been doing it at or for over two decades.

The next scene shows him in his element: a crime scene. His on-scene partner, Detective Taylor breaks it down for him:

“Neighbors heard them screaming at each other for like, two hours. It was nothing new. But then they heard the gun go off. Both barrels.”

This line showcases that Somerset is not alone in his apathy. The neighbors around this murder victim are so used to the screaming that they didn’t care enough to do anything about it. That is, until the gun went off, which foreshadows a line from John Doe near the end of the film:

“Wanting people to pay attention, you can’t just tap them on the shoulder anymore. You have to hit them with a sledgehammer. Then, you have their strict attention.”

It’s almost a cautionary statement to Somerset about his own apathy and foreshadowing the dangers that lie therein: people could get hurt. While the movie will tragically drag Somerset back to this crazy world and keep him there, he does learn to realize that he can’t (or rather won’t) stand idly by, bringing it back to the quote on Page Zero. “The world… is worth fighting for.”

After Taylor tells him that the wife was in hysterics about killing her husband, Somerset ponders a pattern he’s seen; Why do people only realize that they’re taking a life after they’ve already done it? Somerset once again displays his apathy for humanity, showing that he doesn’t care about the woman’s motives, but rather a disdain for having committed murder.

However, there is a larger point here: Mills.

Villains are, by definition, evil. Antagonists do not necessarily fall into that category. Going back to the comparisons of The Lord of the Rings, specifically The Two Towers: Sauron is the villain of the film and the entity they are trying to defeat by destroying the One Ring. By contrast, Faramir acts as an antagonist to Frodo and Sam’s journey to Mordor by taking them captive to Osgiliath, which he does on the orders of his deranged and spiteful father. Faramir later defies his father’s orders and lets the hobbits go free after hearing Sam’s line. He’s not a bad guy, but he is stopping them from achieving their goals in this film and in the end, it’s Sam who convinces him of the theme of the movie(s) that there is some good in this world worth fighting for.

While John Doe is undoubtedly the bad guy and is certainly a good thematic foil to Somerset’s character, the role of antagonist of the film is better filled by Detective Mills. He’s constantly challenging Somerset’s method, ideology, and even his resolve in several scenes of the film. The two even become good friends because of this (Somerset respects Mills, even if he finds him a bit excessive). But one aspect of an antagonist’s role is to fight with the protagonist during the climax over the thematic premise of the film. During this movie’s third act, it’s not John Doe with whom Somerset battles, but Mills. Doe is merely the subject about which they debate.

Mills wants to kill John Doe in a blind rage, but Somerset reminds him that John Doe is a cunning mastermind who wants Mills to shoot him. Mills’ struggle then becomes knowing that he’s going to extinguish a life but decides that he “doesn’t care” and kills John Doe, regardless. The script even has Mills say:

“Okay… He wins.”

Somerset will even ask him if it made him feel better, and Mills responds in the negative. Thus, his disdain for the lack of realization in this first crime scene foreshadows the final battle in the film.

PAGE FIVE

The first line of Page Five shows Detective Taylor saying that this crime scene is complete, save for the paperwork. Somerset won’t be convinced, but there is more to this line. Taylor accepts what he sees and doesn’t think anything else needs to be done about it. Aside from further pressing the apathy theme, this also comes back into play more throughout the story.

Mills repeatedly dismisses John Doe as “a nutbag” and gets into confrontations at the drop of a dime because he is “feeding off his emotions.” The captain will later state about the Gluttony victim that “someone has a problem with the fat boy and wanted to torture him.” And even the person who makes Lust’s death tool says that he didn’t look into it because he “thought it was performance art.”

Somerset’s next line goes counter to this, suggesting that his apathy is not just about his own lack of care, but the lack of it in other people as well. He asks whether the victim’s child saw the incident. While Taylor is dismissive and doesn’t think it matters, he’s wrong. If the kid had seen something, they now have an eyewitness. It shows us Somerset is intelligent and looks deeper into problems that may be simple at first glance, which can be a costly mistake to those that don’t. Furthermore, it’s a good Save the Cat beat. Even though Taylor doesn’t seem to care, Somerset shows that he still does… somewhat.

Taylor then berates Somerset, telling him he’s going to be glad to be rid of him because he’s sick of Somerset constantly asking these kinds of questions. It’s likely that Somerset, over the years, has opted for his partners or the whole department to stay overtime just because something felt off with him. It’s a little bit of between the line reading.

After Taylor leaves, he’s replaced by Mills, the antagonist of the film. To reiterate: an antagonist is not necessarily the bad guy. In fact, Mills actively assists in CATCHING a bad guy, which helps the reader get on his side right away. It’s also worth noting that he comes in right as Taylor says that he doesn’t care, almost to visually show us that Mills is about to bring change to the world around him and challenge Somerset’s worldview.

His introduction tells us that he’s fifteen years younger than Somerset, muscular, and handsome. This is likely setting up a common trope for cop films: young cop paired with older cop. Se7en chooses to subvert this cliché.

In most buddy cop pairings, the tone of the film is comedic, and this script has shown that it is anything but. The duo are also usually deuteragonists, meaning that they share story and growth throughout the film, evolving into two halves of one whole. Most of these duos also have the young cop learning at the feet of the older one. In this film, it’s altered significantly. Though Somerset does try to take Mills under his wing, the latter is too stubborn to accept any help or philosophy that clashes with his own. By the end of the film, Mills will show zero growth, which is a staple of being an antagonist, changing the dynamic between these two characters.

PAGE SIX

Page Six is mostly dialogue, showing the first meeting between Somerset and Mills. The conversation serves as a way for them to size each other up as well as introduce our antagonist.

Somerset suggests that they go to a bar to talk, but Mills would rather go directly to the precinct. The old cop tries to take charge, but the young cop immediately attempts to take that control away. Mills does sense, immediately, that he may have crossed a line, so he tries to smooth it over.

Somerset asks Mills why he wanted to come to this city. In addition to reminding the reader that his goal is to leave this place, it also shows him trying to take on the mentor role for Mills. But as Mills notes:

“I don’t follow.”

While this line is partly about Mills not understanding Somerset’s question, thereby insinuating a gap between their intellects, it also reveals a significant detail about Mills’ character. He doesn’t want to follow; he wants to lead. Mills is a bit of an Alpha dog. He’s hot headed, confrontational and “feeds off his emotions.” This will ultimately be his undoing when he becomes… “Wrath.”

Somerset clarifies his question: he’s curious as to why Mills put so much effort into getting transferred.

Mills counterattacks his question, saying that his reasons were probably the same as Somerset’s were before he quit. There’s contempt in Mill’s line, suggesting that he thinks Somerset is not what he used to be or that he doesn’t think the aged detective deserves any praise for giving up. There’s a pause between the end of the line and “quit,” indicating an intent to impact Somerset. He’s over the hill and it’s time for Mills to take over. His attempt to disarm Somerset has an added notion of a desire to prove his own intelligence by making a quick deduction about him.

As the script has shown, Mills’ words are true: Somerset has lost his reasons for being on the service. His ennui about the world around him consumes him and his apathy for it has caused him to want out. He’s leaving because he doesn’t understand the city nor his place in it. And he no longer cares. Though it’s unlikely that Mills was trying to do so, he’s got Somerset’s character to a tee.

Somerset, in his only weak portion of the fight, rebuts Mills’ claim by stating that Mills just met him. He’s challenging the younger detective by doubting that he’s intelligent enough to make such an apt deduction so soon after an introduction.

Mills, backing down, reiterates that he’s not understanding Somerset’s question. So, he clarifies further:

“You fought to get reassigned here.”

This one word highlights the key difference between the pair: Mills is a fighter and Somerset has had all the fight taken out of him. Somerset continues the line, stating that he’s never seen anyone do it the way that Mills has, suggesting that Mills is going to challenge Somerset’s worldview and may even surprise him before the movie is over.

PAGE SEVEN

One common trope of the young cop/old cop pairing is that the older cop doesn’t typically feel like the younger one knows the difficulties of the job. Such is the case for Detective Somerset. However, Mills tries to convince him that he is, indeed, qualified to be there. Even going so far as to remind Somerset that he has been working homicide for several years at this point. Somerset’s response:

“Not here.”

Somerset reminds Mills that his experience is conditional. In any profession, a simple change of location can make all the difference in the world, like being a big fish in a small pond thrust into the ocean realizing that their size is minute in comparison. While Somerset chastised Mills for judging him too quickly, the seasoned detective also pegged Mills quickly, locking down his personality right away.

The conversation ends with Somerset asking Mills to remember this first lesson over his last week on the job.

The scene transitions to a Monday morning via the second title card. For many people, Monday is regarded as the worst day of the week; they go back to work or school and the freedom or joy of the weekend is in the rearview mirror. Therefore, it’s an interesting note that this is the day that the first murder occurs, as the script will take the reader to the Gluttony victim on Pages Nine and Ten, but Tuesday will not start until Page 23.

Mills awakens in his new apartment, with a set up that is oddly similar to Somerset’s: moving boxes are everywhere and the sound of the chaos outside resonates in the room. The only key difference is that Mills has a wife: Tracy. If the script is going to the trouble of showing the similarities between the two characters, then it is the differences between the pair that will end up being important later. Since Somerset is older than Mills, and yet he is alone, Tracy’s existence implies that there is an element of tragedy to Somerset’s life regarding a relationship. Later, he will confess to Tracy that his biggest regret (and that guilt is likely the largest cause of his ennui) is that he forced a miscarriage in his fiancé. The element of tragedy implies one other thing: Tracy is in danger.

As seen previously, Somerset uses a metronome to drown out the noise and fall asleep. But Mills wakes up and is immediately frustrated. This implies that Mills’ default emotion is anger and that he thrives in chaos.

Like the introduction of Somerset, light comes through the windows and shines on a football trophy. Mills looks at this trophy and smiles fondly. This visual storytelling shows us that Mills is a jock. If the archetype holds true, then he’s not going to be the sharpest tool in the shed but is going to be quick to anger. However, he’s only dim-witted in comparison to Somerset, which was hinted at by Detective Taylor earlier. There are a couple of instances that Mills shows he’s not just some dumb jock.

However, the quick-to-anger quirk is definitely true of Mills. Several times he chooses to listen to his anger rather than sense and logic, even if he’s got the time to consider all his options. This is a character trait that will continue until the very end of the film.

PAGE EIGHT

Tracy awakens to see her husband staring at the trophy, but then the phone rings. Though it seems almost innocuous, a cop getting a call to come to a crime scene, the reader has just witnessed the inciting incident, as this is the call to the Gluttony Scene.

Transitioning to said scene, Officer Davis gives the rundown to Mills and Somerset, the latter of which takes out a homicide kit. This is probably standard procedure for homicide, but we can assume the precaution is part of Somerset’s personality as well.

They go into the building, when Davis reveals that no one checked to see if the victim was alive. Mills isn’t too thrilled about that and challenges him.

Davis responds with:

“Unless he’s breathing spaghetti sauce, he ain’t breathing.”

The implication here is that the victim has died while eating. What the reader will later learn is that he died from eating and that he was forced to do so.

PAGE NINE

Continuing from Page Eight, Davis retorts to Mills’ condescension by mentioning the state of the victim. Mills wants to keep fighting, but Somerset stops him. The fact that Mills stops shows the reader that he does have some humility, but also that he is trying to make a good impression on Somerset. He did say during their first meeting that he didn’t want to get off on the wrong foot and clearly thinks here that that’s what’s happened. So, he backs off… for now.

After making their way inside, Somerset asks him what the point of the argument was going to be. Mills fires back with some airtight logic:

“How many times has he found bodies that weren’t really dead.”

Mills is angry at Davis for not being thorough on his job, what he’s actually angry about is that Davis doesn’t seem to care enough to do his job properly. And negligence is a bad thing in jobs where you literally hold life and death in your hands. Somerset tells him to drop the argument, reminding us of his own apathy.

This line is one of the first to challenge Somerset’s world view, and further shows how far Somerset has fallen into his depression.

ADDENDUM: Not present in the script is a tiny beat between Mills and Somerset. When they arrive at the crime scene, Mills is holding two cups of coffee and tries to give one to Somerset, who refuses. This further enforces the idea that Mills feels like he didn’t make a good first impression and is trying to fix it, but Somerset all but confirms it.

PAGE TEN

The script details some set dressing for the victim’s apartment: dim lights, yellow pillows that were once white, a stack of many reader’s digest magazines, and two televisions. Visual storytelling shows us the derelict nature of the building but implies the nature of the inhabitant: likely someone who didn’t get out much.

So, Page Ten ends about a quarter of the way in. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that, aside from the slug lines, there are only seven lines total on this page. However, considering this shortness, I’m going to break a rule here:

PAGE ELEVEN

The importance of the dim lights is emphasized here, with Somerset and Mills still requiring their flashlights to see in the apartment. This creates a gritty and creepy atmosphere for the scene and helps in setting the tone of the film. But it also serves as a visual metaphor for the beginning of the mystery.

At this moment, Mills and Somerset are poking around in the dark, looking for clues. They aren’t even aware that this is a murder yet, let alone the first of a gruesome spree. They don’t know or understand the significance of the scene before them; they’re completely in the dark. By contrast, the climax takes place during the early evening (stated to be around 7 pm), and the sun hasn’t set during that time. But that’s also when John Doe lays bare the finale to his magnum opus, and everything is fully revealed.

Further set description shows a mess of dirty dishes in an uncleaned kitchen, implying that someone was cooking a lot without regard for the health of the inhabitant, which the reader will later learn is exactly the point.

Then the script reveals the victim: an obese man, face down in a plate of spaghetti. At first glance, the reader is meant to suspect that it’s a random event, i.e. that he died from a health condition related to his weight. Is this even murder?

Even Mills goes so far as to suggest that it’s likely a coronary. This line does further lend credibility to Mills being the antagonist. He’s a hypocrite. Not three pages ago, he was berating Davis for doing a shoddy job and making a snap judgement, but here he is, doing the same thing.

And Somerset proves him wrong by examining the victim’s ankles to reveal razor wire wrapped around them. It’s murder after all. It can be argued that Somerset’s lack of apathy in this situation contrasts with what has been shown thus far. However, the reader gets another aspect of Somerset’s personality: his curiosity. Even though he will repeatedly tell his captain that he doesn’t want the case, Somerset can’t help but get involved. He wants to know how it ends. Even before the climax, he tells Mills that he’s staying on until it’s done so he can see what happens. And it’s this curiosity that Mills will exploit and will change Somerset… though not necessarily for the better.

CONCLUSION

While the following scenes will show some debate about whether they’re going to work the case or whether they can work together, by the end of these first *ahem* ten pages, the script has shown the first of seven victims, introduced the protagonist and the antagonist, set the tone of the film, and heavily implied its thematic premise of apathy.

This is achieved using clever and careful dialogue choices, as well as subtle character actions and set descriptions, adding to the visual storytelling of the script. In a story that uses its themes to combat the ennui of apathy, it’s inspiring that so many details can provide such insight into the world and its characters.

So, truly, the devil is in the details.

About the Creator

B.D. Reid

A competition-recognized screenwriter and filmmaker, building to a career that satisfies my creative drive but allows me to have time for friends and family.

Comments

B.D. Reid is not accepting comments at the moment

Want to show your support? Send them a one-off tip.