I Wish More of My Teachers Had Said "I Don't Know"

The importance of reminding students the adults don't have it all figured out

I always loved science. My brain is wired analytically, and I always did well enough at anything quantitative. I also crave new knowledge, and I’ve always been too ambitious for my own good.

When I had to decide what to “do for the rest of my life” at 16 when I was applying to university, I ended up choosing to go to film school.

What? But Mich, what about new knowledge? What about analysis and science?

I’ve asked myself the same things over the years, until I finally came back to it—my first true love, really, was maths. But in school the words, “We don’t know,” or “That has yet to be truly explained” were rarely uttered. In my grade 11 maths class, I did a brief project on the history of the Riemann Hypothesis (yeah, overachiever, I know). Where did I hear of Riemann’s? Not in school. On a TV show. A crime drama called Numb3rs, to be precise. Not a single teacher mentioned the fun part of maths—about how the Fibonacci sequence appears in flowers, or how the golden ratio can be found in nautilus shells. My physics teacher didn’t talk about how we don’t understand what 95 percent of the universe is actually made of—rather they told us that everything was made up of atoms (the honours class got a brief mention of up and down quarks, and a meagre introduction to general relativity at least). Chemistry was fun, because there were explosions, but they never bothered to tell us that the Bohr model of molecules/atoms is really not how nature is structured.

They made it seem like the “adults” had it all figured out. Like there wasn’t anything new to discover—even though I graduated high school months before the Higgs-Boson particle was discovered at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.

I was young, and ambitious, and a little stupid. I chose to start out in the arts, because I wanted to create, to pioneer something. I didn’t think I’d be able to do that in the sciences, because the adults around me made it seem like we understood the world.

Thankfully, I remembered my love of maths, and anything quantitative in a finance class of all things when I went back to school for business (the artist thing didn’t work out, clearly). Fast forward a couple years, and I’m studying mathematics (and economics) with the goal of ending up in mathematical physics.

I didn’t get here by accident. My ambitions (and perhaps my youthful stupidity/bravado) haven’t abated. Quite the opposite. In pursuing this ambition, I started learning everything I could on my own. Enter the Royal Institution—their Youtube channel to be precise. I don’t know what brought me there originally, but I ended up watching a talk by Dr. Harry Cliff—an English particle physicist working with CERN’s LHC-b project, among other things—talking about the LHC’s role in exploring the standard model of particle physics. In addition to reminding me how much I hungered for understanding of this knowledge, it gave me hope with a single sentence (aside the part about the LHC being around for years, because I know it’ll take me years to get there)

“If you hear the word ‘dark’ in physics, you should get very suspicious, because it basically means that we don’t know what we’re talking about.”

If someone had told me something like that in high school, I would have jumped into science wholeheartedly in post-secondary. Maybe that’s just me, but the idea of learning new things, teaching new things, and the potential to help define human understanding of a concept are just too tempting to pass up.

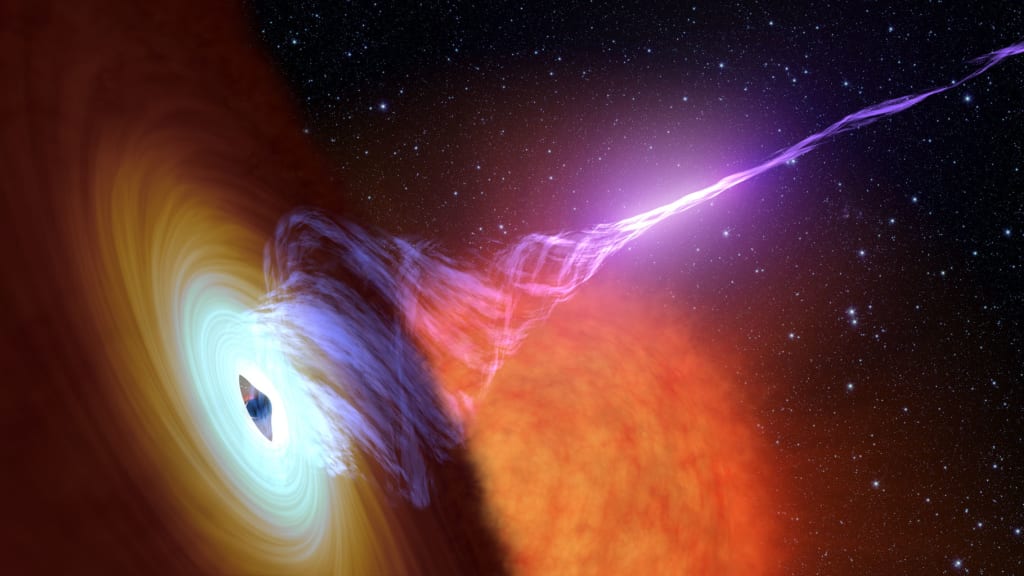

The rise of scientific engagement has been aimed at young people to get them interested in the sciences. We tell them all the cool things that science has done for us, like iPhones, the first photo of a black hole, moon bases and AI. Yes, these things are cool. Yes, they create engagement. But what if, instead of telling them all the things we do know, we tell them what they don’t. Because as soon as you tell someone—especially a hungry, ambitious young mind—that there’s a mystery out there that no one has found the answer to, you’re telling them they have the chance to discover something, that they have the chance to contribute. That they can boldly go and illuminate paths, so humanity can tread where it has never been before.

About the Creator

Elias Veren

Just a queer mess that sometimes writes things of an abstract, fantastical, or horrific nature - sometimes all three. Mixed race, disabled, neurodivergent serial hobbyist trying to find themselves through creativity.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.