One of the most mysterious mountain ranges in the world is not visible on any ordinary map. You can’t see it on the most popularly used flat map of the world, the Mercator projection, or on the Peters projection that is a popular (and more accurate) alternative. On a spinning globe, the plastic axle at the North Pole often covers it up, as if there’s nothing to see.

But this is where you can find the Lomonosov Ridge, a vast mountain range running from the continental shelf of Siberia towards Greenland and Canada. The mountain range stretches for more than 1,700km (1,060 miles), its highest peak is 3.4km (2.1 miles) above the ocean floor.

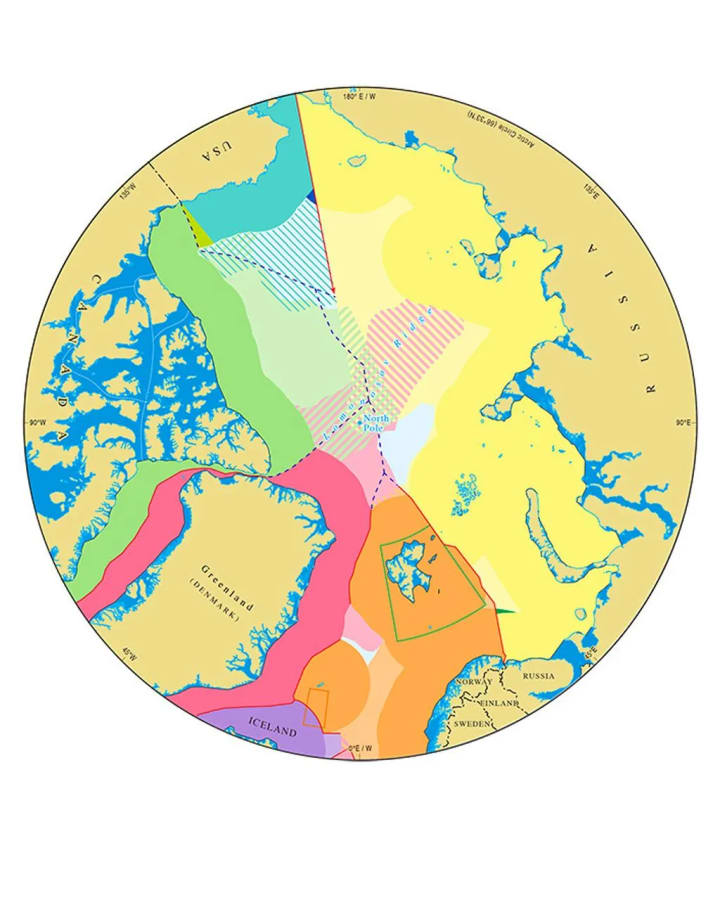

This little-known mountain range is at the centre of three nations seeking sovereignty over the seabed around the North Pole. According to Denmark, the mountain range is an extension of its autonomous territory of Greenland. According to Russia, it is an extension of the Siberian archipelago Franz Josef Land. And according to Canada, it is an extension of Ellesmere Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut.

So who is right?

You might also like:

The frozen ship drifting to the pole

What will an ice-free Arctic look like?

The quest to map the ocean floor

The ridge was first discovered in 1948 by researchers on one of the Soviet Union’s early expeditions to the central Arctic. From a camp on the sea ice, the Soviet scientists detected unexpectedly shallow waters to the north of the New Siberian Islands. It was the first hint that the ocean was split into two basins by the ridge, rather than being one large, featureless basin, as previously assumed. In 1954, the researchers published a map showing an underwater mountain range, which they named after the 18th-Century poet and naturalist Mikhail Lomonosov, who had predicted 200 years before that such features would be found in the Arctic basin.

Today, more than 70 years after the ridge was detected, it remains an enigmatic feature in one of the most poorly mapped seafloors in the world. Even with modern ships passing powerful 864-beam arrays of sonar down through the Arctic waters, the resolution of the ridge is only in the order of hundreds of metres. That’s like being just about able to distinguish one end of an athletics track from the other side.

In such a poorly charted area, new mapping expeditions always lead to surprises. “It’s like putting on a new pair of glasses every time,” says Paola Travaglini, who has led mapping of Arctic the seafloor on expeditions aboard Canada’s CCGS Louis S St Laurent icebreaker. “You never know what you’re going to find.”

But mapping the peaks and valleys of this mountain range alone isn’t enough to determine how it formed, which landmasses it is a part of, and which nations can credibly claim it. To do that, scientists need to physically get hold of a piece of the ridge – a lump of rock that might be able to reveal a geological trace of the mountain range’s origins.

Hard evidence

Christian Knudsen, a geologist at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), was involved in analysing a chunk of the ridge. Scientists from Denmark, Canada and Russia have dredged rocks from around the mountain range, but the difficulty is always proving that what they’ve picked up is really a part of the ridge, rather than just some pebbles or boulders lying around that could have come from anywhere. Ice sheets formed on Arctic coastlines have a tendency to sprinkle detritus all around the seafloor as they drift, leaving a trail of “drop stones”. A drop stone that hitched a ride on an iceberg from Siberia or northern Canada could easily be scooped up from the ridge by accident, giving a false result.

But it is hard to take a piece out of a mountain range that is submerged beneath hundreds of metres to several kilometres of water, topped with floating sea ice. It’s hard enough to get there in the first place. A team of researchers from GEUS, led by Christian Marcussen, managed to dredge the sample from on board the Oden, Sweden’s research icebreaker, in 2012.

Inside he found something unexpected: layer upon layer of fine lines, much like tree rings

Marcussen's scientists were able to dredge the ridge at a depth of 3km (1.87 miles). Among the rocks they drew back to the surface was an orange-coloured lump around the size of a rugby ball. This was the material that Knudsen later analysed. “In the beginning no one paid attention to this rust-orange-brown crust, but I was curious to see what it was,” says Knudsen. “So we cut it.”

Inside he found something unexpected: layer upon layer of fine lines, much like tree rings. This layered crust was rich in manganese oxide, which forms in nodules on the seafloor where there is very little sediment. The nodules take many thousands of years to form, so it was a hint that the rock that had formed in-situ at the ridge, and was not a drop stone. Knudsen measured the age of the rock using beryllium isotopes – Beryllium-10 is a radioactive isotope that forms in the stratosphere, and over time decays to Beryllium-9. By measuring the ratio of the two, Knudsen could get the age of the rock.

What he found was a steady eight-million-year timeline of the rock’s history through the many layers of the crust, with the oldest rock next to a base layer of sandstone at the bottom, and the outer layer very recent.

“It proved that this rock has been sitting in this position for eight million years in the polar basin – since before the Ice Age,” says Knudsen. It felt, he says, like he was Sherlock Holmes finding a footprint outside the window. “I could prove that this rock was actually from the Lomonosov Ridge.”

But it was sandstone below the rust-orange crust that had the most interesting information about the mountain range. The lines formed in this rock were folded, a signature mark of sandstone that has been crumpled in a mountain-building event. The clays were turned into micas as the mountain was made, beginning another isotope “clock” as it did so – this time relying on an isotope of potassium – which helped Knudsen to date the age of the mica, and therefore of the mountains themselves. It turned out the mountain-folding event was 470 million years ago. The sand grains that made up the rock, though, were much older – closer to 1.6 billion years.

Why mountains matter

As coastal nations, Russia, Denmark and Canada of course already have sovereign rights over the seafloor close to their own shores. Coastal countries can establish an Exclusive Economic Zone that stretches up to 200 nautical miles (370km) from shore, which gives them rights to activities like fishing, building infrastructure and extracting natural resources, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. That law also permits a country to extend its rights over the seabed further – if there are seafloor features that they can prove are an extension of their continental shelves.

While the ridge may well be an extension of Greenland, if you look at it from the other end it is also an extension of Russia

For such a seafloor feature to count in a country’s favour, there has to be evidence that it is a piece of submerged land – and not an oceanic ridge that has always been underwater and has little to do with the country’s land mass.

What Knudsen’s findings boil down to is evidence that the Lomonosov Ridge is indeed submerged land, and not formed from seafloor spreading, like the mid-Atlantic ridge that runs like a seam from Iceland down towards Antarctica. The same finding is backed up by other studies, including seismic research into the structure of the crust, led by Ruth Jackson of the Geological Survey of Canada, and other crucial evidence, such as extensive research to map the seafloor in the area.

“It’s definitely continent,” says Knudsen. “And it’s continent that is similar to what we find in eastern Greenland – it is a continuation of Greenland, that’s our main point. We have taken the rocks, proved they actually came from the ridge, and we understand what they are. And then we are home,” says Knudsen.

The thing is, while the ridge may well be an extension of Greenland, if you look at it from the other end it is also an extension of Russia. Rocks of a very similar sort have been found on the Russian archipelago of Franz Josef Land, to the north of Novaya Zemlya, Knudsen notes. And Canada, too, has evidence that the Lomonosov Ridge is a prolongation extending from Ellesmere Island, perhaps not surprising given that Ellesmere nestles close to Greenland via a narrow strait just 20km (12.5 miles) wide at the northern end.

In fact, it’s perfectly possible that the Lomonosov Ridge is Russian, Canadian and Greenlandic all at once.

Redrawing the map

The Lomonosov Ridge is central to each of the submissions Russia, Denmark and Canada have made to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. As long as there are seafloor features no less than 2,500m from the surface extending as a continental feature from a country’s established shelf, it can act as a spine for extending their territory. When three countries use the same spine of submerged land, it results in several areas of overlap. That includes a 54,850 square nautical mile area around the North Pole all three countries lay claim to.

So, what next? Does that mean these three Arctic nations are due to clash over territorial disputes?

When there are international tensions around borders, the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf won’t weigh in

The answer is almost certainly not. If they were to become hostile, the carefully crafted – and eye-wateringly expensive – process of gathering scientific data and going through the decades-long UN process would fall apart. These three countries have committed to a peaceful and cooperative means of drawing their lines on the map in ratifying the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The “Arctic Five”, which includes the US and Norway, also signed a declaration in 2008 committing to orderly settlement of Arctic borders, which helped to deescalate matters after Russia planted a flag at the North Pole seabed the year before.

In fact, when there are international tensions around borders, the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf won’t weigh in. “One thing the commission says is ‘avoid politics’. Any disputed sovereignty over land and they’re not even touching it,” says Philip Steinberg, a professor of geography at Durham University and director of the International Boundaries Research Unit.

The Falkland Islands, or Malvinas, are a case in point. “As soon as the commission received a submission from Argentina, Britain raised an objection,” says Steinberg. The commission’s response was to consider Argentina’s broader claims to an extended continental shelf, but not consider the waters around the disputed islands.

Patriotic posturing

Just because the nations have committed to a peaceful process, it doesn’t mean that there won’t be political intrigue.

Right now, the UN commission has not concluded on any of the three submissions, though Russia, which was first in line to make its submission in 2001, appeared to hear positive early signals towards the end of last year, says Klaus Dodds, professor of geopolitics at Royal Holloway University of London. “The commission had clearly released an indication to the Russians that they were sympathetic to their submission. That is exceptionally exciting to the Russians. After a mere 20-year wait, I think they’re going to get what they want – which is confirmation that the continental shelf and those submarine ridges belong to one another.”

That puts Russia in a strong negotiating position, says Dodds. “You can imagine what’s going to happen. President Putin will stand somewhere very grand – you’ll have an enormous map of the Arctic beside him – and he’s going to say: ‘The Arctic is ours.’”

Such posturing might be expected, but it should be taken with a pinch of salt: the UN commission doesn’t have any legal powers. Its findings are only about scientific credibility of the evidence, and the commission doesn’t actually recommend where to draw the lines on the map. That has to be done through diplomacy.

“You’ve got to take a deep breath and go and negotiate with Russia,” says Dodds. “Putin has made it clear the Arctic is essential to Russia’s survival. I think there’s going to be some really, really tough negotiating. I wish Canada and Denmark well, but it’s going to be difficult.”

Russia, though, has not been as bold in its submission to the UN as it could have. The area of seabed Russia has marked out stops soon after the North Pole, well short of the territorial seas of both Denmark and Canada. Denmark, on the other hand, has been more intrepid and submitted evidence from right along the Lomonosov Ridge, up to Russia’s Exclusive Economic Zone. “Denmark has said we’re going to do all the science all the way out until we hit Russia,” says Steinberg. “But Canada and Russia said there’s no way we’re going to get seabed that close to another nation, so why bother?”

Northern riches?

One of the biggest misconceptions around the central Arctic is that overlapping territorial claims is leading to hostility and even the possibility of conflict. When Steinberg’s department first published the map showing the overlapping claims in 2008, it caused a considerable stir. “The map went viral and people were saying, ‘Oh my god, look at the war that’s about to happen in the Arctic,’” Steinberg says. “I continually have to battle that impression.”

Sovereignty over the seabed doesn’t change a country’s rights or ability to control shipping, or to carry out commercial fishing

Part of the misconception is because of what people believe to be at stake. Oil and other natural resources are often assumed to be the main appeal, sometimes encouraged by government statements. Canada pulled its initial Arctic extended continental shelf claim from a broader submission to the UN including its Atlantic shelf in 2013, reputedly because the initial Arctic claim did not include the North Pole. At the time, John Baird, then foreign affairs minister, said: “We are determined to ensure that all Canadians benefit from the tremendous resources that are to be found in Canada’s far north.” Canada submitted a broader claim, this time including the North Pole seabed, in 2019.

But these “tremendous resources” could turn out to be nothing, as Andrea Charron, director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at the University of Manitoba, has noted.

“It’s utterly clear that the substantive oil and gas resources lie in countries’ immediate Exclusive Economic Zones,” says Dodds. “In the extended continental shelf, the resource value is frankly dubious.” Steinberg, too, says that in terms of economic potential, the central Arctic is “way down anyone’s list”.

Shipping access through an ocean with increasingly thin and shrinking ice cover in summer is also not a motivator. Sovereignty over the seabed doesn’t change a country’s rights or ability to control shipping, or to carry out commercial fishing. It’s only about what is in, on and under the seabed. If the extractive industries aren’t economically viable – or even technologically possible there at present – then what is the draw?

One reason is national pride, notes Steinberg. “For several of the Arctic nations, northern-ness and claiming the north – and even claiming the North Pole – is such a huge part of national identity. Canada prints postage stamps with Santa on it; kids grow up thinking Santa is Canadian.” And there’s also the simple reason that “if you don’t make that claim, somebody else will”, he adds.

Cultural value

“This is a region that has attracted attention and interest for centuries,” says Ingrid Medby, senior lecturer in political geography at Oxford Brookes University. “The North Pole is steeped in myth, right? We learn about the North Pole as the home of Santa Claus as children. It’s part of the mental image we have of the world, and yet it’s a space most people will never travel to. It’s something that lives primarily in the imagination.”

This idea of the pole is important for political and symbolic reasons, says Medby. “The North Pole is very far from land, so not anywhere that would be inhabited as such, but the Arctic Ocean goes much further south and touches the land of the Arctic coastal states. In terms of their culture and identity, ideas of this ocean are often connected with the histories of coastal nations.”

Indigenous communities are increasingly acknowledged as a crucial part of sustainability, in the Arctic and elsewhere

None more so than for Arctic’s indigenous inhabitants, whose lives have been closely intertwined with the ocean and the ice for thousands of years. “We are dependent on the ice in a way that no others have ever even come close to,” says Dalee Sambo Dorough, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, who have argued Inuit communities should have rights and jurisdiction over the Arctic sea ice.

But consultation of indigenous communities has been “uneven” when it comes to efforts to extend sovereignty northwards, says Dorough. “In some cases states have engaged in dialogue and discussion with Inuit representatives as rights-holders of lands and territories, and in other cases there has been little to no consultation or direct dialogue.”

As climate change has escalated interest in the central Arctic, the Inuit Circumpolar Council has called for states to engage with Inuit and other indigenous groups and respect their rights. While the central Arctic seafloor might seem to have little to do with climate change (especially if any hydrocarbons there aren’t extracted), being seen to be an environmental “steward” or “protector” in the Arctic is something that Canada, Denmark and even Russia are pushing for.

Indigenous communities are increasingly acknowledged as a crucial part of sustainability, in the Arctic and elsewhere. “Though it’s far into the future, we still have to be mindful of the interconnected nature of the whole ocean and the coastal seas, as well as the potential threats for Inuit and other Arctic indigenous peoples, and the Arctic states,” says Dorough.

It’s likely to be decades before there is an answer from the UN commission on the science that underpins all three countries’ claims. And it’s possible that the US still may submit a claim in the future, shifting the picture again. Norway, which claimed a more modest extended continental shelf excluding the pole, and with only a sliver of overlap with Denmark, has already had its recommendations from the UN.

For a mountain range claimed by three different nations as their own, the task of using the Lomonsov Ridge to redraw borders has so far been a remarkably peaceful one. The inaccessibility and harshness of the Arctic environment is one factor that gives nations a strong incentive to collaborate, sharing the costs of long scientific expeditions using icebreakers that can cost upwards of $250,000 (£198,000) a day.

The UN process, offering international credibility and requiring peaceful cooperation, is another reason that negotiations over this remote mountain range at the bottom of the sea are unlikely to descend to Cold War depths.

About the Creator

Baru Ku

"Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.