The Koyukon People, Lake Sacandaga, and the Power of Nature

A discussion of what is natural and unnatural with regard to human interaction with the environment.

Clean, beautiful, and dotted with forested yet sandy islands, Sacandaga Lake lies in the Adirondacks nestled between Bald Bluff and Bernhardt Mountain. Originally named “Sacandaga Reservoir”, the lake itself was created in the 1920s to flood the Sacandaga River and the Hudson River (which were known to devastate nearby areas with uncontrolled flooding). Costing over 12 million dollars, “This was the biggest reservoir in the area ever to be built. Farms, wood lots and entire communities would be replaced by 283 billion gallons of water” (Frasier).

Although admittedly it was quite unnatural in its creation, over the years, Sacandaga Lake itself has not only transformed into a beautiful outdoor destination during each summer season, but it has also transformed into a thriving waterfront and aquatic ecosystem teeming with wildlife. Given the necessary time, the lake has flourished, and is now able to support a wide range of species apart from human lake goers—species that anyone can catch a glimpse of on a regular basis if they pay close attention. Bald eagles, juveniles and adults alike, are often spotted gliding overhead or fishing near the islands; carp are often seen grazing in the shallow waters around the docks; mergansers that nest clutches of up to twenty eggs are eventually seen paddling around with their massive broods; ducks are seen perusing the rocks and pebbles near shore looking for bread scraps and bugs; blue herons are seen strutting about the shrubs and greenery of the sandbars on stilted legs; even the occasional mated pair of loons is seen breaching the surface of the white caps in windy weather only to disappear beneath the depths again to escape any prying eyes.

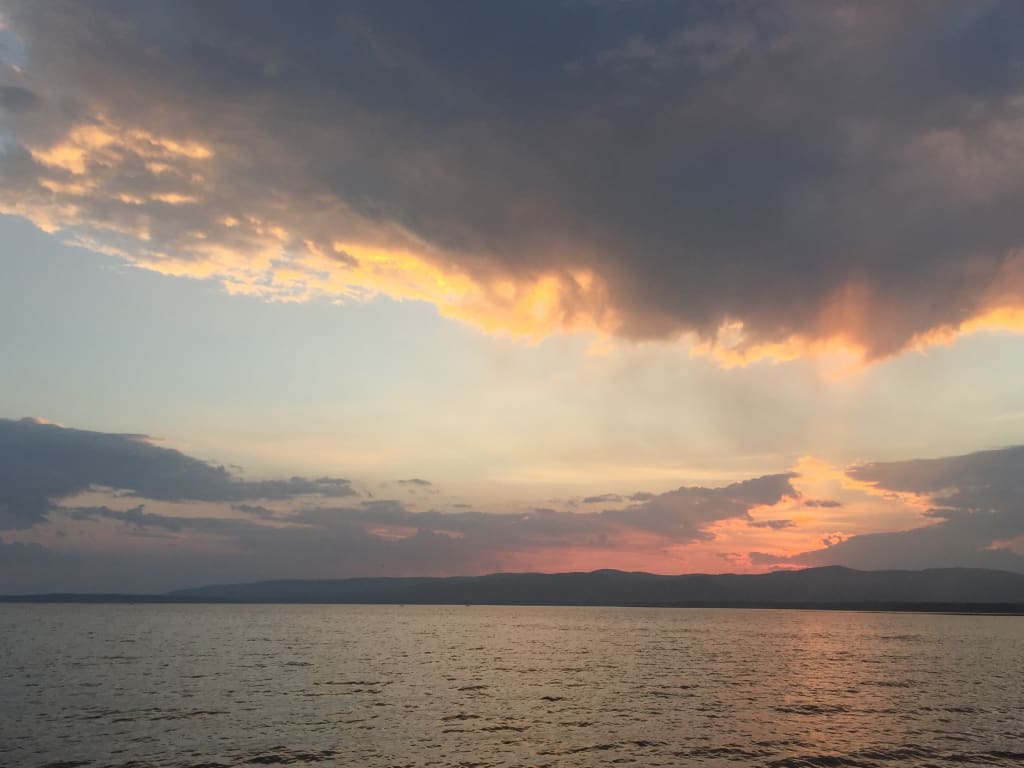

For the extent to which the lake itself and all the life that lives within and around it have adapted over the years, I consider this a natural and somewhat wild place that I am deeply in love with. Whenever I am able to dig my toes deep into the warm sand granules on the beach of one of the islands, see the sun melt over the distant mountains blanketed by a violet hue at dusk, or see some of the spectacular wildlife for myself, I feel both at home and absolutely free.

Because Lake George is only 45 minutes away and is more well-known, comparatively speaking, Sacandaga Lake is much quieter. Though I wish more people would visit the lake so they can experience it for themselves, at the same time, I’m happy with the current population of people who frequent it—I prefer the bustling more touristy nature of places like Lake George to keep a safe distance. The people who know the Sacandaga have a tremendous amount of respect for it and want to see its sparkling, clean waters remain as such for years to come. We bought our lake rights years ago, back when I was about four years old, so that we could have that same connection to the lake itself and everything it has to offer.

While I feel a deep-rooted connection to Sacandaga—its waters, its vibrancy, its serenity—whatever connection I feel to the lake cannot compare to the emotional and spiritual feeling of oneness the Koyukon people felt towards the natural environment surrounding them. According to the article, “The Watchful World” from American Environmental History, in regards to the Koyukon people, “The intimacy of their relationship to nature is far beyond our experience - the physical dependence and the intense emotional interplay with a world that cannot be directly altered to serve the needs of humanity” (Nelson 28). While I consider Sacandaga Lake now to be quite a natural place, I reiterate that it was unnaturally made. It started off as a man-made reservoir built in order to redirect flooding. This is the perfect example of mankind reshaping the environment to suit human needs with little regard for environmental impact. Although thankfully Sacandaga has since become a healthy ecosystem, this manipulation of what might have been relatively untouched wilderness goes against everything the Koyukon people believed in and taught. For them, nature was not something to be tamed or controlled. It was, quite literally, alive all around them, “aware, sensate, personified” (Nelson 28). Nature was something very powerful that demanded respect.

The Koyukon people, residing in central Alaska along the Yukon and Koyukuk Rivers, are an Athabaskan people that relied on hunting and trapping prior to European settlement. Unlike the European settlers, the Koyukon sought to live off of and better understand the land they loved rather than attempt to settle it or make it bend to their will. The Alaskan natives told stories of the “Distant Time” when animals trapped in human form once roamed the earth, and in these stories of both the natural and spiritual worlds, “Detailed explanations are provided for the origin of natural entities and for the causation of natural events” (Nelson 28-29). The Koyukon people believed, as they still do to this day, that the story of all human beings and natural phenomena are entwined, dating back to a time incomprehensibly distant from now, hence the name the "Distant Time".

As I recall my experiences with nature—submerged in the cool waters of Sacandaga, perched on the peak of Crane Mountain, or even ankle-deep in the stream running behind my house—I too feel a certain sense of oneness with nature, an entwined experience with it, but it is different than the Koyukon people. When I am in the woods alone, or find myself walking the shoreline of one of the humble islands gracing the lake, I never feel completely alone with nature itself. Perhaps it is the feeling in the back of my mind that there are always other humans around no matter how aloof I make myself. Even with all of Sacandaga’s hidden coves, there is no island, beach, or sand bar that is completely concealed from other people. There are always passing boats, the occasional jet skier, planes passing overhead, and houses poking out from the trees on every shore.

But I think there is something else I feel when I am alone in what I consider to be a natural place, especially when I am visiting my beloved Sacandaga. One of the islands in particular is so small, it only has space enough for one boat to anchor onto shore, even when the water line has retreated to its lowest point in the summer. My family and I have come to call this island “Little I” for its size, and it holds a very special place in our hearts. Whenever we want to spend the day as a family, we leave our dock early in the morning, and claim Little I for ourselves, usually for the entire day. There is little evidence of people here—only a small fire pit—and the island’s minuscule size ensures we can enjoy it without anyone invading our privacy. There is a cluster of trees for shade, lots of large boulders we used to explore when we were younger, shallow water perfect for cooling off, and above all, a beautiful view of the mountains. Whenever we spend time on Little I, I always feel an overwhelming sense of calm, and home. The breeze rustling the leaves on the trees, the water splashing up against the mammoth rocks guarding the island’s gentle shores, the buzz of the damselflies in the bushes, they all give the island its own identity, almost bringing it to life.

In this sense, I can relate to the Koyukon people in their belief that the natural world around them is personified in a way. I think when people are given the opportunity to truly be present in a beautiful natural setting, they should pause and really take a closer look at the world around them, as they would find it is very much alive and deserves our respect. As Nelson writes with regard to the Koyukon people, “The interchange between humans and environment is based on an elaborate code of respect and morality” (Nelson 41).

When it comes to Sacandaga, I believe the majority of lake-goers hold a tremendous amount of respect for the lake itself and all its wildlife, however, there are some differences compared to the Koyukon people. For instance, Sacandaga residents and lake-goers are very protective and proud of the presence of Bald Eagles around some of the islands. One of the larger islands, known as “Scout Island”, always has at least one nest of eagles hidden away in its trees. By early summer, many boats will make their way down the lake in order to catch a glimpse of the hatchlings, hoping to see a parent guarding the nest or maybe even a juvenile attempting flight. While the eagles are impressive birds that are now making a comeback (as they were once considered an endangered species), it’s difficult to gauge just how many boats pay the island a visit throughout the summer. Is this disrupting the birds? Should we be giving them more space? I believe the Koyukon people would leave the island alone entirely and allow the birds little to no human contact if possible. Nelson writes, “Koyukon people follow some general rules in their behavior toward living animals. They avoid pointing at them, for example, because it shows disrespect, ‘like pointing or staring at a stranger’” (Nelson 36). This is a stark contrast with those visiting the eagles at Sacandaga. Despite people not being allowed to park their boats on shore, people often point the eagles out once the nest is spotted, use binoculars to see them, and attempt to take pictures of them and the island. While these actions are not intended to be disrespectful, it certainly could constitute an invasion of privacy when considering the lake wildlife and their needs.

After carefully evaluating my own experience with the natural world—specifically with Sacandaga—and comparing my experience to that of the Koyukon people, it is clear that when it comes to assessing what is “nature” versus man-made or “anti-nature”, nothing is cut and dry. Sacandaga Lake was the result of a human need to control seasonal flooding. Though this was a monumental project demanding hefty funding, manual labor, and significant changes to the land itself, in this case when the reservoir was created, there was a happy ending. Not only was the flooding controlled (appeasing the people in nearby towns), but the lake ended up transforming into a thriving ecosystem. Despite the continued presence of people on the lake itself, the waters are clean, the wildlife and vegetation are plentiful and healthy, and the people who frequent the lake appreciate and respect everything it has to offer—they never want to see it polluted, neglected, or put in jeopardy by irresponsible people who lack the same connection people like myself and my family have with it.

As Nelson concludes, “For traditional Koyukon people, the environment is both a natural and a supernatural realm” (Nelson 40). While the supernatural aspect of the environment is a concept I continue to deliberate, I firmly believe Sacandaga Lake remains to be a natural place that will remain a part of our family for generations to come. I just hope it will always be the same Sacandaga I knew growing up.

***

Work Cited

Frasier, L. (n.d.). Great Sacandaga Lake History: The Reservoir. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from http://www.visitsacandaga.com/history/

Louis Warren, editor, American Environmental History (New York: Blackwell Press, 2003), p. 28-41

The Leader-Herald. (2019, August 5). The bald Eagles of the Great Sacandaga Lake. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://www.leaderherald.com/news/local-news/2019/08/the-bald-eagles-of-the-great-sacandaga-lake/

About the Creator

Madison Newton

I'm a recent graduate of Stony Brook University with a degree in Environmental Humanities and Filmmaking. I love writing and storytelling, and I love sharing my work so I can continue to improve my written voice.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.