The West’s goal to reach a net-zero carbon footprint is focused on energy consumption. BHP has committed to going net-zero by 2050, and the UK’s electricity production is slowly shifting away from gas & electricity.

For good reason — natural gas power plants produce a whopping 437 to 758 grams of CO2-equivalent per kilowatt-hour; whilst wind turbines in the UK — throughout their lives — produce 11.8g per kWh. Once up and running, the carbon footprint of green energy sources are far superior. Which is good to hear.

Outside of this, many governments are turning to other initiatives — such as subsidising solar panel installation, or banning the sale of new petrol and diesel-powered cars. However, many followers of the net-zero goal overlook their own footprint. It’s a chronic issue within the field, as PR teams and politicians crow about how much progress they’re making.

For example, one of the biggest PR moves made by the British government in its ‘Build Back Greener’ campaign, is bringing the ban on ICE vehicles forward to 2030. Secretary of State for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy — The Rt Hrn Kwasi Kwarteng - labelled this move as a “bold step toward net zero”.

That problem of net-zero projects lies in the sourcing and mining of earth metals. I touched on this before, but let’s take your average electric vehicle battery — and replace all 31.5 million Internal Combustion Engine cars on Britain’s roads with EV equivalents. This would take 207,900 tonnes of cobalt, 264,600 tonnes of lithium carbonate, 7,200 tonnes of neodymium and dysprosium, and 2,362,500 tonnes of copper.

Massive numbers aside — these are monstrous quantities of batteries. The battery production for the UK — this small island alone — would demand twice the current annual production of cobalt; an entire year’s global production of neodymium, and three-quarters of the world production of lithium.

So, we need more mines.

Prof Richard Herrington, Head of Earth Sciences at the Natural History Museum of London, has already stated the necessity of mining in reaching net-zero.

“We’re probably only talking about a short-term spike in mining but we have to work quickly…The public are not in this space at the moment; I don’t think they understand yet the full implications of the green revolution”.

The public does not understand this, thanks to decades of greenwashing.

Canada’s Creighton Mine is one of the world’s largest subterranean mines. At its deepest, the SNO site sits 2 km underground. The vast underground shafts, lit by harsh white floodlights, echo and roar with the diesel engines of massive bulldozers.

Half of the global industrial greenhouse gas emissions in 2015 were traced to just 50 companies in heavy fossil fuel industries, including 20 mining companies, according to a report from the Carbon Disclosure Project.

The artificial reduction of emissions by the mining — and its related industries — is rampant. This occurs in two major forms: the first is what I’ll call ‘scope-dropping’.

The leading GHG protocol breaks greenhouse gas emissions into three parts, or ‘scopes’. Scope 1 and 2 emissions focus on the company’s direct energy usage in company vehicles and offices, and the amount of electricity they use in their own in-house production. These are both mandatory to report.

Scope 3 emissions are those created by the company’s franchises, outsourced production; and logistics. This is where the bulk of emissions stem from — these are not mandatory to report.

This is a loophole exploited by many companies: the Tesla Gigafactory is reported as net-zero, for example.

Ironically, the mining industry itself is often overlooked by companies wishing to portray themselves as ‘net-zero’. As the third scope is not legally required to report, it is chronically easy for companies to simply ignore the source of their materials.

Which is fantastic! Now, mining companies such as Wheaton Precious Metals can state that they’re fully carbon-neutral.

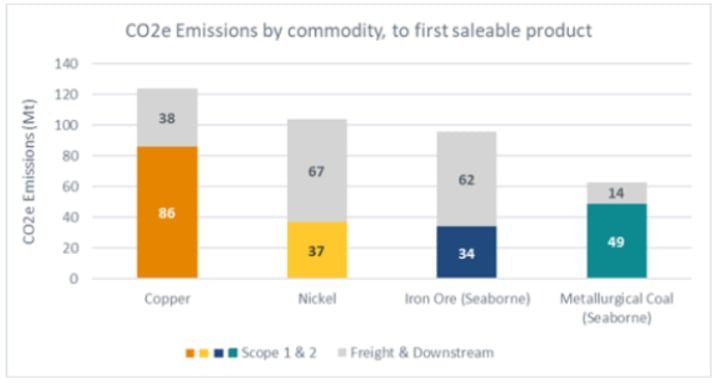

The data below shows the work of Skarn Associates, wherein the amount of CO2-equivalent emissions are measured — throughout the supply chain — for the 4 most popular earth metals:

Companies have consistently ignored their own freight & downstream emissions, and it’s vital that cross-supply chain data is more normalised. Here, we can see the immense amount of emissions created by the mining industry and its peers in 2019.

The total emissions for the production of all 4 of these earth metals was equal to the amount produced by the UK in 2018.

So, whilst the first easy cop-out is to just ignore one’s emissions, the second cop-out is in the form of carbon offsetting. This is the process of taking as much carbon out of the atmosphere as you’re emitting. Companies such as ecologi allow businesses and individuals to purchase ‘offsets’: some companies, such as Ryanair, have even attempted to push this cost back to the consumer. Only 1% chose the option of an offset flight.

Furthermore, the act of sequestering carbon is still pretty mis-understood: there’s massive demand for better understanding around how different habitat types and land management activities actually absorb carbon.

So, sure, mining isn’t exactly the most carbon-neutral, sustainable practice in the world. This is mildly concerning, when mines make up 80% of the global demand for electricity.

There are the inklings of change within the mining industry, however. South African mines are increasingly moving to solar energy to help offset emissions. However, these projects are still limited with the red tape of bureaucracy — any amount of panels over 1,000 MW requires a special licence.

Furthermore, the Creighton Mine is slowly phasing out its diesel vehicles toward an all-electric fleet. This is a promising start, as diesel accounts for 46% of a mine’s energy demands. However, these changes seem to pale in the face of the problem’s importance.

Ultimately, carbon offsetting does not reduce the amount of emissions pumped into the atmosphere — they just export them elsewhere, so the company can produce a nice whitepaper on how they’re closer to net-zero now. The mining industry has already been criticised for their over-reliance on carbon offsetting.

As we gallop toward a net-zero future, it’s important to keep a tight view on what exact future we want. Part of a truly sustainable future is holding companies accountable for their true carbon output. The other half is seeing past the lie: production matters, and the better-aware the consumer is, the more we can demand that companies are transparent around their own production. Only when we see products as a product of their supply chain can we ever hope to address the frightening reality of mining’s place in the future.

About the Creator

Rk.ke

Follow the Omnishambles

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.