I spent an hour or two barreling around the monadnocks of Sutherland in a post-bus once. It was a bright March day, with a fresh covering of snow and I was on my way to the Northwest Highlands, heading towards not only the top left hand corner of Scotland, but also the most ancient part of Europe where the rock is up to three billion years old. That was the day I realised that every landscape has a way of explaining itself.

One of the epic landscapes of Britain, this part of Scotland was, until recently, attached to the Canadian Shield - the geological nucleus of North America. And, aside from the wild antediluvian overtones of the hummocky plateaus around Loch Assynt - an ambience that suggests you might suddenly encounter a herd of herbivores, each the approximate size of a parish church around the next bend - there is also a transatlantic otherness about the place.

On bright, snow-bound days, the landscape wears an American smile; everywhere gleams toothpaste white in a glaring, razor-thin sunlight, with only silhouetted fence posts and the occasional lone stag standing out as details in a minimalist tableau. On that day, the landscape was reduced to its absolute bare essentials - all grand lines and sweeping curves under an arching blue sky as Donald the post-bus driver managed to share an observation about the snow between light-hearted tales of life in adversity in the Highlands. His observation, which was accompanied by a mischievous twinkle in his eye, was that 'snow reveals more than it conceals'.

On that particular day it was really the only way of looking at things, especially the larger-than-life vistas of the Northwest Highlands - a landscape formed when one slab of crust was pushed and thrown forty miles over another.

A challenge to the view that Britain's scenery is no more than a foothill to the world, these mountains are of a scale and sublime grandeur that reflects their ancient origin as Himalayan behemoths. The mountain prospect is home to such little detail that the impact of the scenery is only enhanced by snow. On a wet day in November, they can appear unadorned, stark and unforgiving - like the scenic equivalent of your local tax office. Under alpine conditions, every arête is honed, every corrie is picked out in the light and the whole thing gleams like a drawer full of knives.

Britain has seen Namibian-style deserts, volcanoes of Krakatoan disposition and tropical, cerulean seas, not to mention mile-high glaciers, continental collisions and apocalyptic earthquakes.

Elsewhere, the landscape is usually more subtle but no less exotic and always reveals something about itself in the viewing. At various times in the long history of these islands, Britain has seen Namibian-style deserts, volcanoes of Krakatoan disposition and tropical, cerulean seas, not to mention mile-high glaciers, continental collisions and apocalyptic earthquakes. While all of this - like pre-Brexit relevance - is now safely tucked away in the glory of Britain's past, each of these leaves a legacy of tell-tale signs that can help unearth the deep history of an area. So that often, rather than the grand lines of escarpments and brutal overtones of a mountain range, understanding the landscape starts in the intimate details of the countryside around you.

Beech and ash trees, for instance, love the well drained, thin and light soils found over chalk, and many a ring of them stand crowning a prominent down. A few years ago, I camped with a clear view of Chanctonbury Ring on the South Downs in Sussex. It was Lughnasadh - the pagan equivalent of a 'harvest festival', only without the rusty tins of pineapple. I watched the swing and bob of lanterns from a safe distance as witches danced around trees set on top of a vertiginous scarp slope every bit as forbidding as their moonlit escapades. The scarp of the South Downs stretched east and west like the hanging wall of some great tear in the landscape.

The South Downs rise to little more than 800 feet yet, from a perspective afforded by the various country roads which follow the bottom of the scarp slope along its length, they have the visual authority of a mountain three times their height. The gentler dip slopes of the escarpments follow the dip of the chalk beds, rucked up like a rug by the same collision - of Africa into Europe - responsible for the building of the Alps. Twenty million years ago, the North and South Downs were connected by a giant arc of chalk, a super-down that stretched from Hampshire to Agincourt; a wide, green bridge the height of modern Snowdon along its crest. Most of this chalk has now been washed away, leaving only the limbs of the arch, the 800 foot high stumps of the North and South Downs, on which humans now dance on high days and holidays, desperately seeking some arcane source of power from the Earth. Perhaps they should be careful what they wish for.

Humans have long harvested what they can from the land beneath their feet, but this is particularly so with regard to building materials. The chalk of the South Downs, for instance, is far too soft and friable to be of much use for construction, but its beds contain regular layers of large knobbly flint nodules which are to chalk what diamond is to candy-floss. Flint is super-hard, whereas even a soft spring rain will eventually turn chalk the same way as a Sunday morning Alka Seltzer. Flint - made from a fine-grained variety of quartz - and brick (probably baked from local clay) are used for much of the vernacular architecture on the chalk downs.

The built environment is littered with clues to what lies beneath. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Cotswolds, where whole villages are made of a golden limestone known by geologists - in what sounds like a rather dismissive tone - as the Inferior Oolite.

The Inferior Oolite's particular golden hue, evocative of sepia postcards and all things cosy and old, makes many a Midlands village look as though it was hollowed-out from enormous loaves. In the fields, the oxidising iron found in the limestone that creates this Hovis-grade nostalgia, renders the soil a peculiar orangey-brown, rather like the aspirational 'gold' label coffee brands some of us bought in the 1980s when our aspirations were that much more modest. Away from the country fields, Cotswold limestone reaches the apotheosis of its expression in the Great Oolite - the Bath Stone used for high-status buildings from the Royal Crescent to Oxford colleges - and its warm tones come from the same oxidising iron as the Inferior Oolite that has built thousands of Cotswold cottages.

At Dawlish in Devon, iron oxides colour the cliffs that Brunel's Great Western Railway runs around, darting in and out of tunnels and arches framed with New Red Sandstone, a vibrant carmine that rivals the terra rossa soils of the Mediterranean, while the fertile local fields get their ocherous hue from the same source. Close inspection of the cliffs around Dawlish reveals another aspect of Britain's deep history; you can clearly see the cross sections of ancient desert dunes from 2–300 million years ago when Britain's climate was like that of modern New Mexico.

Inland, the tors of Dartmoor, Bodmin Moor and every eminence but one to the toe of Cornwall offer the traditional granite upland of poor peaty and acidic soil where heather thrives. But one Cornish moor is different. Goonhilly Downs on the Lizard Peninsula is the only place in Britain where Cornish Heath Erica vagans thrives. Unlike every other member of its largely lime-hating family, which includes rhododendrons and bilberries as well as heather, Cornish Heath loves alkaline soils and the Lizard has them by virtue of a slab of oceanic crust which was unexpectedly thrust over the top of continental crust by a 400 million year-old geological sleight-of-hand too rare and exotic to go into here. Even a geological map of relatively low detail shows the Lizard Peninsula as a riot of colour, as if geologists became suddenly influenced by the work of Jackson Pollock and abstract jazz.

Much can be found out about your local landscape from maps, but a detailed geological sheet is not necessary. A 1:50,000 Ordnance Survey Landranger map of the area is ideal, but even one of low detail such as a road atlas, can serve well in finding some features of the landscape that may not be immediately obvious on the ground. Place-names can provide clues to the geography of an area - many of them explicitly mention topographic features like fords, fields, downs, islands, headlands and streams in Old and Middle English, Old Norse and the indigenous languages of the Celtic nations.

A little bit of research can reveal interesting facets and long-forgotten facts about a place, all from its name. The Cornish name for St Michael's Mount - Carrack Looz en Cooz, the 'grey rock in the woods' - reveals that, far from being a few hundred yards offshore in a bay, it was once miles inland in the centre of a forest. Nearby fossilised tree stumps peek out from the sand and dating of them confirms that a rise in sea levels towards the end of the last glaciation was responsible for miles of coastal inundation.

Place-names that feature the element 'bourne' or 'borne' in them usually indicate a stream or spring found in chalk and limestone landscapes. You may find villages named "Winterbourne" - which is a stream that only flows in winter, a particular feature of a chalk landscape. Chalk is porous but in this country most of it rests on an impermeable layer of clay and rain drains through it and along the top of the clay until it reaches the surface as a spring. When winter rainfall raises the water table within the chalk, springs may appear further up the slope. When the water table drops again during the summer, the winterbourne dries up and will leave a dry valley behind. Other dry valleys may be shown on the map or feature in place names as 'combes', glacial features formed when summer meltwater rivers cut valleys into frozen ground, the one time when chalk is no longer porous. It's all a long way from the circumstances of chalk's original formation, built from billions of smidgens of microscopically small shells that settled out of a very warm cerulean sea around 80 million years ago.

Salisbury Plain, the South Downs and most of Hampshire probably looked like this around 80 million years ago.

You can go so far with maps, but for all our modern pre-occupations with measurement, mapping, cataloguing, codifying and tabulating the landscape as if beauty was in the eye of the auditor, our ancestors were way ahead of us if what they left behind is anything to go by. They seem to have had an innate understanding of landscape - or, perhaps, better spatial sense than us. It's possible that we have lost something in our relentless lust for reductionism, maybe we can no longer see the landscape as a whole, but only as an assemblage of imperfectly understood systems.

Stonehenge is the perfect example. We focus on a mysterious ring of stones and forget the landscape around it. The world-famous circle is positioned on an eminence in the landscape - a crown upon a topographical skull - in a way that suggests its builders were not satisfied with merely erecting a temple, but wanted to manage participants' reactions to it. Set some way back from the brow, the henge is hidden from view along The Avenue, the ceremonial route from the River Avon a mile or so to the east. In a piece of pure theatre, Stonehenge becomes visible only on the final approach, where it appears to climb from the horizon like the midsummer sun.

An understanding of the landscape may have been what kept our ancestors alive at times; a better understanding of it now might help us with the problems we have been ignoring since we attempted to disconnect ourselves from the natural world with the grand übermenschian gesture that was the Industrial Revolution.

Going to the Northwest Highlands was a way of feeling the brute force of the landscape again and removing the human reference points. The pillar-like summits like Suilven that rise in an imposing fashion from the hummocky plateau seemed to sum up the prehistoric appeal of the place. Formed three billion years ago, disinterred, then buried again two billion years later, when there were still no complex organisms on the planet; then whittled and gauged away by glaciers to reveal the ancient landscape again, they ooze with the kind of menace completely absent from our modern lives. It is a landscape looked over by odd-shaped mountains - inselbergs or monadnocks like Suilven - laid down when even the dinosaurs were a distant and unlikely possibility.

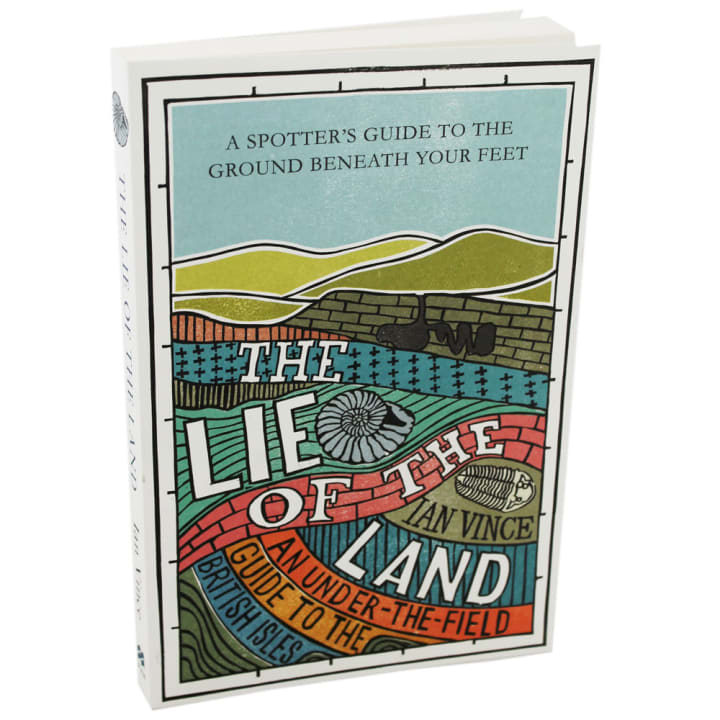

Click on my affiliate link to buy my book (Kindle or paperback) on Britain's landscapes: The Lie of the Land: An Under-the-Field Guide to Britain

About the Creator

Ian Vince

Erstwhile non-fiction author, ghost & freelance writer for others, finally submitting work that floats my own boat, does my own thing. I'll deal with it if you can.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.