Bwana Mzungu and the Spirit Lions

Everything he knew about lions, he learned from Tarzan and Abbott & Costello. Good thing, then, that when he finally went to Africa a visiting professor and world-renowned lion expert was there to set him straight. Here’s a light touch of fictional whimsy, just in time for World Lion Day.

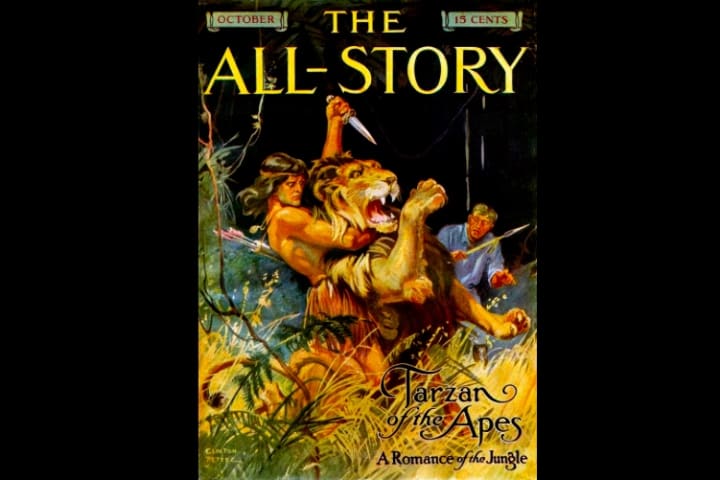

Bwana Mzungu watched too many jungle movies on TV when he was a kid. He saw plenty of jungle movies, and he saw plenty of movie lions.

The King of the Jungle, he learned from timeless classics like Africa Screams — Abbott and Costello! in living black-&-white! — was a fearsome, toothy critter who liked to chow down on European explorers in pith helmets, when those explorers weren’t stepping on what looked like a sturdy root on the damp jungle floor, that is, only to discover the sturdy root was in fact a crocodile.

The lion did double duty as the King of Beats and King of the Jungle, and he was as fearsome as any toothy critter this side of a hungry crocodile who didn’t like being stepped on by explorers in pith helmets. If the explorer was a good guy, one of those dudes who was after diamond thieves when he wasn’t saving damsels in distress, he would be saved — by Johnny Weissmuller, say, in his 1932 Tarzan phase, or by Maureen O’Sullivan, in the years when she played Jane to Weissmuller’s incredibly buff ape man.

When he grew older, Bwana Mzungu resolved to go to Africa himself, to see the King of the Jungle with his own eyes. When he arrived he couldn’t quite understand why the locals looked at him and laughed, and giggled among themselves about what a putz he was. He learned there was a famous lion scientist from America who was passing through town and staying a night at his hotel on his way to a lion research project in the grasslands, a long way away and in a whole other country.

“Why are they laughing at me?” Bwana Mzungu asked the famous lion researcher, who was a tenured professor at a prominent, respected university in the US midwest. “All I’m doing is going to the jungle to see a lion.”

The famous lion researcher’s name was Professor Parker and Professor had some bad news for Bwana Mzungu.

“You won’t find lions in the jungle,” the professor told him. “Even if there were lions in the jungle, you wouldn’t see them. They’re shy. They hide from people, especially if those people are on foot. And it’s kind of hard to drive your car in the jungle.”

“But the movies—“

“The movies are wrong.”

Bwana Mzungu was crestfallen.

“Plenty of monkeys, though,” Professor Parker said. “Chattering happily away. That part is real.”

“And crocodiles?”

“Oh, yes. Crocodiles are everywhere,” Professor Parker said mischievously. “Anywhere there’s water. Including the washroom in your hotel. Like I said, anywhere there’s water. Snakes, too. Always be careful when you go to the washroom. You never know what might be coming up through the pipes.”

He paused. “The only lions you’ll see in the jungle are ghost lions, and even then you won’t see them. They’re Spirit Lions. Reincarnated spirits. Sensed, perhaps, but not seen. If you want to see a real lion you have to go the grasslands.”

“There weren’t any grasslands in Africa Screams, or in the Tarzan movies.”

“You’re watching the wrong movies,” Professor Parker said. “Haven’t you seen The Lion King?”

“I guess I’ll have to go to the grasslands then,” Bwana Mzungu said. “This is going to be an expensive holiday. More than I thought it would be.”

He sat there sadly, then realized that while he had one of the world’s foremost lion researchers — and a university professor to boot — sitting right in front of him he might as well learn more about lions while he could. The professor had been interviewed at length, after all, in a documentary movie called The Truth About Lions: Everything You Wanted to Know About Lions But Were Afraid to Ask.

“What are the biggest misconceptions about lions?” Bwana Mzungu asked.

“Ha!” Professor Parker said. “Where do I begin?”

Lions are vanishing in the wild, the professor said. They’re in serious trouble. You see them in zoos, but zoos are not the same as in the wild, and no zoo lion can ever be freed back into the wild. Not one. Never been done, and never will.

Those that are left in the wild are persecuted relentlessly. There are a handful of national parks — mostly grasslands — where they do well, but those parks are surrounded by people, agricultural farms and pastoral cattle herders, and the gene pool is shrinking. Most people don’t know that fewer than 20,000 lions remain in the wild. To put that in perspective, elephants — also endangered — number some 400,000 in the wild.

“I heard males are lazy and sleep all day,” Bwana Mzungu said. “Females do all the hunting.”

“Not true,” Professor Parker said. “When there is plenty of food, in the green season and during the wildebeest migrations, they hunt as a cooperative. Some females will act as a wing and others act as a centre. The wings drive the prey toward the centre. When the zebras and wildebeest move somewhere else, though, which is half the year, the only prey animals that remain are buffalo. Gazelles are small but often too quick for a lion, and are not much of a meal. Buffalo are big and tough, and no female lion, or even a group of females, can bring down a buffalo on their own. That’s when the male gets up off the ground and tackles the big boy himself. A buffalo can kill a lion with one sweep of its horns or a well-timed kick. That’s when the males really earn their keep.”

“What else do the males do?”

“They protect the pride from other males. No male lion ever died of old age in the wild. They’re taken out by other lions. Younger, stronger lions, who move in and take over the harem.”

A male lion’s age can often be read in the size of its mane. Lions’ manes often grow longer the older they get. A lion who’s long in the tooth tends to be long in the hair as well. That hair can get unkempt, but still: That male is a survivor. For now.

Manes can grow up to 16 cm in length and are a sign of dominance. As well as being attractive to females, manes are believed to protect lions’ necks and heads from injuries during fights.

It takes a village to raise a family. Female lions raise each other’s cubs, and will even suckle other lioness’ cubs. The most successful prides are those where the females tend to have cubs at the same time and the cubs are all roughly the same age. The females are almost always related; they’re sisters and aunts.

Long live the king — or not.

There is no king of beasts per se, or queen. They’re neither a patriarchy nor a matriarchy. Lions are the only social cat, but their social interaction is complex and deeply layered. They’re socialist! The Lion King missed that part.

“I never thought I’d come all the way to Africa,” Bwana Mzungu said, “only to learn the kIng of beasts are basically Commies.”

“Socialist,” the professor said, “not communist. There’s a difference.”

But wait, there’s more.

Lions don’t need vast quantities of standing water to survive. They get much of their water needs from what they eat, and will even sample plants like the tsamma melon on occasion.

Some lion populations have even adapted to semi-arid desert.

Lions are hearty eaters. They will eat as much as 40 kg of meat in a single sitting — a quarter of their body weight. This is because they don’t know where their next meal is coming from. It’s evolution — not survival of the fittest so much as survival of the most adaptable.

They like to sleep, but don’t make the mistake of assuming they’re lazy. There’s a reason why lions seem to sleep all day. They hunt at night.

You don’t see that in the movies.

“You should see fewer movies,” Professor Parker said, “and read more books.”

His eyes twinkled.

“Have you read my book?”

“You wrote a book?” Bwana Mzungu said.

Yes, the professor replied. “All good book stores have it. Even Amazon.”

It’s amazing what you learn when you get around, Bwana Mzungu said.

“Isn’t it, though?” the professor replied, and then rushed to catch his plane.

World Lion Day is observed each year on August 10. Its aim is to raise awareness and gather support for lion conservation. Lions are listed as “vulnerable” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of endangered species.

About the Creator

Hamish Alexander

Earth community. Visual storyteller. Digital nomad. Natural history + current events. Raconteur. Cultural anthropology.

I hope that somewhere in here I will talk about a creator who will intrigue + inspire you.

Twitter: @HamishAlexande6

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.