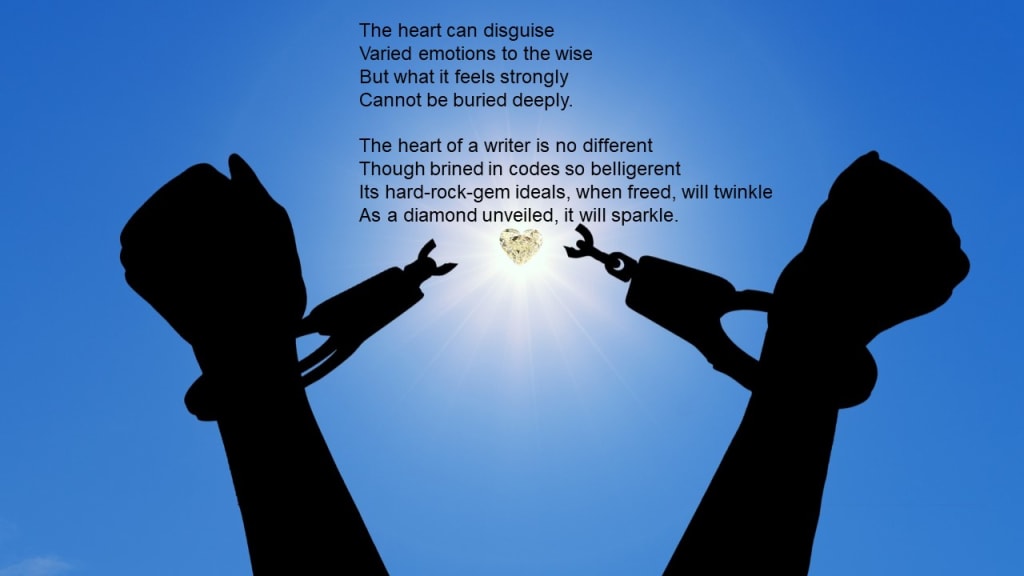

Breaking Out of the Prison of Conventions

A writer’s journey in discovering the hard gem in her

As a writer, no-one would call me a conventionalist.

As editor, no-one would pin a tag on my back and label me a feminist.

But I dared to break out of the existing mold at the time, with fear at the back of my mind about being fired or losing, instead of gaining, readers.

This was the challenge that I faced in the early part of my journey as writer and editor.

***

I WAS offered a position as editor in the biggest publishing house in the Philippines when I was in my mid-20s. This was in the early 80s, a time when editorships were offered, not applied for. It was a very big deal for me, a newcomer.

As editor, part of my job was to approve scripted short stories. About 10 were published weekly in the two titles I was managing; a few saw print in the other titles handled by four other editors.

It was not part of my official job description to be the editor in-charge of approving scripts for the other titles in my department. But that was what I did. It was fine. I enjoyed my job, although reading a minimum of three to four dozen scripts a week could, at times, be a chore.

In this country from the 1950s to the 1990s, reading illustrated story-magazines was a favored pastime of the masses. It was cheap. It was entertaining. It was available everywhere.

It was big business – for the publishers, for circulation distributors, for retailers and proprietors who owned comics rental shops.

It was also a major livelihood for many writers. They looked at short story writing as a means to an end – from writing short fiction to serials and novels; from there, writing teleplays and screenplays, to being film directors.

At the very least, hopeful short-story writers also would not mind being offered a seat in the editorial office of any of the other publications.

It was these tantalizing hopes that drew the most number of aspiring scriptwriters towards writing for illustrated story-magazines. They especially chose the publication where I was editor.

The thinking was that if they passed the set high standards, they could make it in all the other publications. This was true.

***

And strictly did I adhere to applying quality standards when I approved stories.

It did not bother me when I heard about complaints: that I was tougher than the editor-in-chief (true), or that I played favorites among contributors (not true).

When a certain joke from a small group of new writers reached me, that they would gang up on me one day because the stories they submitted to me were all rejected, that still did not bother me.

I understood their sentiment. How could they not feel bad? They were rejected, not once, but multiple times.

Their rejection slips contained the reason why their stories were not accepted. I was thorough in that regard, explaining story flaws. I was helping them improve their craft. But they did not look at it that way. They even ignored my suggestions for rewrites.

Bothersome bid to disapprove

What concerned me was when the editor-in-chief, who had to initial all advance payment recommendations from editors, called me to his desk. He was not happy about one script that I approved.

The story was about a female social activist, penned by a female writer. I defended the story. I said illustrated story-magazines should not only always entertain. It should reflect reality where possible, and that it should also educate, but subtly.

That discussion with my boss was repeated at least three more times involving other scripts.

The stories, written by two women authors, were outside the usual happy-ending tales we accepted.

It involved domestic abuse and gay relationships.

In the story, it depicted domestic abuse as unacceptable, and that women should not just cower in a corner and take the maltreatment. They could and should fight back. Not physically, but seek help from family, friends, neighbors, the police and social services.

Women, I added, should not be perpetuated (in stories) as weak and powerless. That was wrong. Men and women are equal.

As for love between same-sex couples, I insisted that it should be treated (in the stories) with respect. Not as insulting caricatures; not as shallow, comic representations.

I realized, at the back of my mind, that the editor-in-chief could nullify my approvals. That was his right. He could also fire me, easily, for venturing out of the accepted formulaic happy-no-sensitive-social-problem-ridden stories.

Despite my dread at losing a coveted job, I stood my ground.

While a majority of stories I accepted had obligatory feel-good endings, I fought for stories that I believed should be out there, read by the masses. I knew in my heart that the stories I approved would resonate with a chunk of our readers.

My editor-in-chief relented, with a deep sigh. He initialed the petty cash vouchers. I was relieved.

***

Looking back to that moment, I felt proud. I discovered deep inside me a hidden nugget, perhaps as hard and as shiny as a diamond, with regards to what I strongly believed in.

I did not imagine, until that time, that I would have the guts to defy accepted conventions in writing stories meant for entertainment. It was like breaking out of metaphorical prison.

And this occurred in a place and at a time when female empowerment was not inclusive, and in a medium where same-sex relationships were usually depicted with mockery.

***

A FEW years later, I was offered by a local publisher to sign up as exclusive romance writer. My contract lasted 10 fruitful years.

The books were distributed in the Philippines, but the locals sent copies to kin and friends working overseas – meaning, in most countries in the world. Returning overseas workers for their holiday also brought copies of the local romance novels when they flew back to their work abroad.

Again, the unconventional in me deviated from accepted local romance-novel formulas.

I presented my female characters as not traditional; they were strong, not weak; they had minds of their own, not obsequious. They were smart, pretty smart. Social issues and concerns were woven into plots.

A lot of research went into each book. I wanted to not only entertain but to also impart new knowledge and correct data.

Then a marketing staff of my publisher let off this thinly disguised slap. She said that my books sold faster in the business district than in other places. I could take it as a compliment. But it wasn’t. The allusion was that I should cater to those with less education.

Keenly aware of the shiny bit that has settled snugly in my chest, I knew that I could not do that. Not even for the money, no. I had never treated my readers with condescension.

I requested a meeting with my publisher. I asked him, point-blank, whether he would require me to dumb down the romance novels that I write when my exclusive contract was up for renewal. (No, I didn’t tell on his marketing staff who implied the same.)

My publisher was surprised at the question. He said no, adding with emphasis that I should stick to my type of romance, content, and writing style.

***

I was elated, even thrilled.

To have my publisher (and other editors and publishers in my post-romance-novel life) validate that breaking out of the box is a good thing, is nothing short of wonderful for me.

I’m keeping this nugget, a round brilliant cut, not only next to my heart but also in my sanguine spirit.

***

As a writer, those who know my body of work would not call me a conventionalist. I write all sorts.

As an editor in conventional and related media, I was labelled tough and “merciless” with my editing pen.

None, however, would regard me as feminististic. I have an open mind. I supported, when I could, raw talent when I saw it no matter what their pronoun was.

***

Thank you very much for reading!

LinkedIn | WordPress | Twitter | Facebook | Amazon Author’s Page | pinoypub.ph

About the Creator

Josephine Crispin

Writer, editor, and storyteller who reinvented herself and worked in the past 10 years in the media intelligence business, she's finally free to write and share her stories, fiction and non-fiction alike without constraints, to the world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.