Sports and Politics Walk The Line

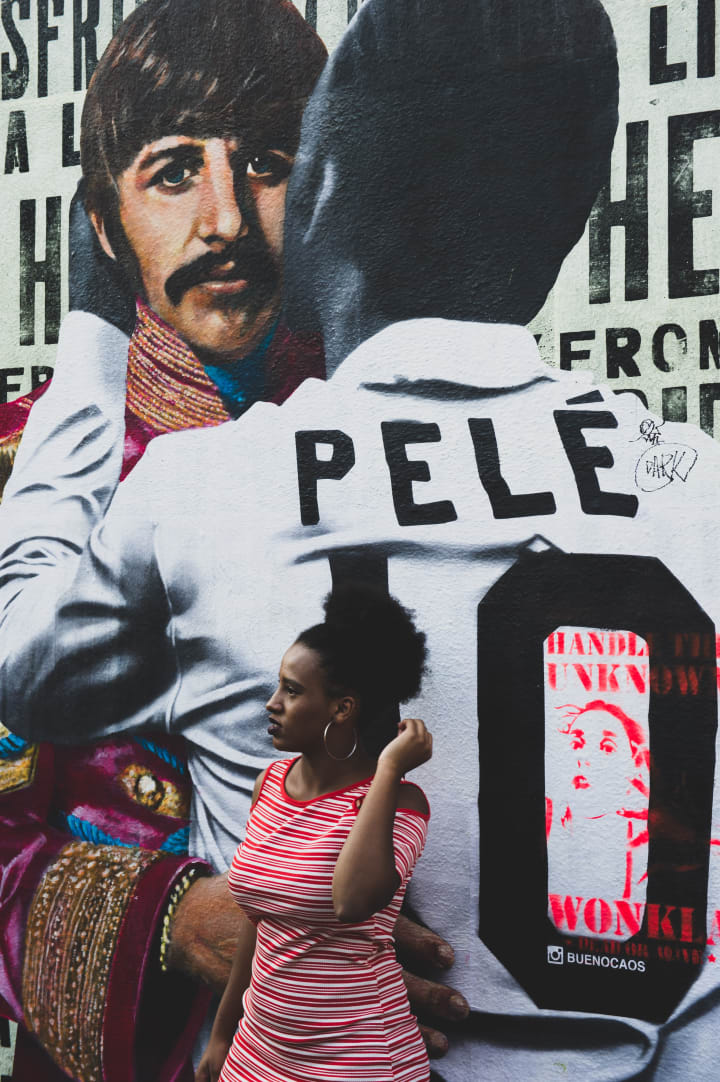

A new Netflix documentary about football great Pelé focuses on the ever narrowing line between sports and politics.

Football’s greatest legends: Diego Maradona, Lionel Messi, Neymar and now Kylian Mbappé, choosing a worthy candidate for the title ‘Greatest Player in the History of the Game’ is both spectator sport and blood sport, and changes with the times.

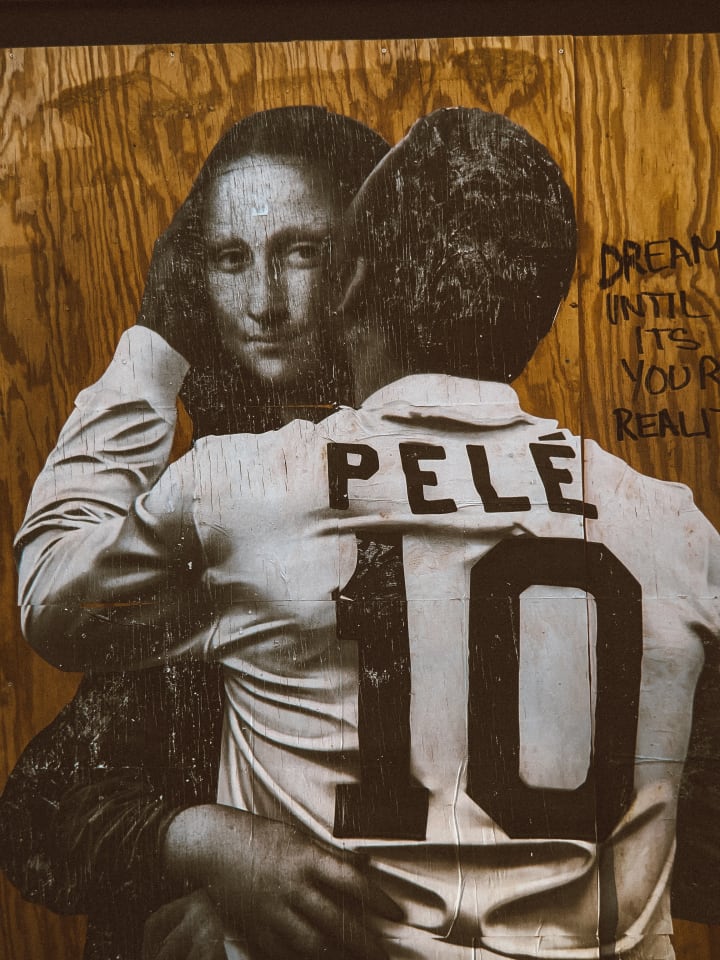

Above them all, though, one name stands out, and it’s hard not to sit down to the fine new Netflix documentary Pelé and not be reminded just what a profound influence the man born Edson Arantes do Nascimento had on the Beautiful Game.

That’s why it’s a shock to see Pelé, now 80, emerge in the film with a walker as he hesitantly sits down to a face-to-face interview with Pelé filmmakers Ben Nicholas and David Tryhorn, Nicholas Taylor.

In many ways Pelé is a remarkable film, despite early reviews that complain there are few layers to the man himself, that despite his prowess at playing football and a decades-long career in which he became the only man to win three World Cups, all with his native Brazil, Pelé, the man himself, is not that interesting a subject to pin an entire documentary on. He doesn’t have the charm and charisma — “the BS personality,” as one wag put it — we have come to expect of our celebrities in the social media age. As good as Pelé was at playing the Beautiful Game — he singlehandedly invented the term — he never would have made it as an influencer on YouTube.

And yet.

The shy, retiring, 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) would-be footballer born into poverty in Bauro in the Brazilian state of São Paulo would go from relative obscurity to superstar at age 17 in the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, and then national hero in the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, during one of the most turbulent and tumultuous times in Brazil’s history.

He did it, as the filmmakers show in Pelé, by showing a rare ability to anticipate opponents and score goals equally well his left and right foot, to be a single-minded goalscorer and yet also a team player. He was talented but also hard-working, a rare combination, both skilled at scoring goals and knowing precisely when to pass to a teammate in a better position to score. There’s a joke said of the Real Madrid great Cristiano Ronaldo, now with Juventus and a candidate in his own right the title of greatest player of his generation, that he doesn’t pass the ball; he loans it out temporarily, with the full expectation that it will be returned. Cristiano Ronaldo is still going strong, still scoring goals at age 36, with five Ballon d’Or awards to his name, though no World Cups. As good as Ronaldo is, and he is very good indeed, he’s no Pelé.

So far, I probably haven’t done much to convince you that Pelé, the film, doesn’t tell you anything you can’t learn from Wikipedia or YouTube.

In a way, that’s true. Pelé, the man, will never hold the room with conversation. His career stats are easy enough to find; there are plenty of highlights of his goalscoring triumphs on YouTube. He has led an interesting life by most people’s standards, full of the trappings of celebrity, fine wining and dining, travel to exotic countries and so on, but his life’s story doesn’t have the electrifying intensity or emotional addictiveness of, say, Lupin or The Queen’s Gambit, Netflix’s two biggest must-sees at the moment.

Pelé’s accomplishments and triumphs on the field are merely prologue. Midway through the two-hour Pelé, the tone changes, and the documentary’s real theme — the story one suspects filmmakers David Tryhorn and Ben Nicholas wanted to tell all along — emerges. Brazil in 1970 was mired in the grip of one of the bloodiest, most oppressive dictatorships in the country’s history, and many people in Brazil, the very same people glued to the TV set during his triumphs on the world stage, expected Pelé to take a public stand, one way or the other. He didn’t.

That becomes the defining theme of the film, and the reason Pelé is so compelling to watch. This is where those critics who’ve complained that the film doesn’t tell us anything about Pelé that we don’t already know, have got it completely wrong.

At what point does a national hero owe it to himself, and those who follow his every word, to speak out about truth and injustice?

The filmmakers press Pelé on that point, and even now the greatest player the world has ever seen is uncomfortable addressing the issue. The film shows how, having won the World Cup for his country in 1970, Pelé accepted an invitation to the presidential palace of Emílio Médici, whose liberal use of torture and press censorship marked a new low in the military’s two-decade rule, even as the country itself enjoyed explosive economic growth. Pelė’s defenders explain, not entirely convincingly, that sport and politics are separate; Pelé himself says his father raised him to always defer to authority, that when someone in a position of power and influence invites you into their home, as Médici did after the 1970 World Cup, you go. You behave as any invited guest would: you smile graciously, accept praise as it’s offered, and keep your opinions to yourself.

To Pelé’s followers, desperate for change, this must have seemed like a terrible, silent betrayal. The junta was using Pelé, parading him before the public as if they were instrumental in making him the sensational player and national hero he was, and taking credit for his World Cup victories. It’s easy to say sports and politics are separate, but the world stage is different. It’s impossible not to watch the Olympics and be caught up in national fervour. That’s why Hitler embraced the 1936 Berlin Summer Games as an opportunity to promote both his populist government and his twisted ideas of racial superiority. That’s why Jesse Owens, the youngest of 10 children and the son of an African-American sharecropper in Oakville, Ala., is remembered to this day. Owens won Olympic gold medals in four events at the Berlin Olympics, single-handedly shattering Hitler’s myth of Aryan supremacy. Owens set a marker for black athletes on the world stage, opening a door that, once opened, would never be closed.

Brazil in 1970 was not Germany in 1936 but still, there are those who worshipped Pelé at the time, who desperately wanted him to take a stand. So many people died, or were tortured, or simply vanished during those tumultuous times. So very many people. They deserved better.

There’s a telling moment toward the end of Pelé, when Muhammad Ali is sitting in the stands at one of Pelé’s games, looking on dispassionately, his face devoid of emotion. Not any emotion that we can see, anyway. It’s a reminder that of all the athletes in the public eye, Ali is the one who confronted injustice head-on, when he had everything to lose. Ali’s activism, his philanthropy, his refusal to back down when told to know his place, is why he’s The Greatest. Pelé is great, arguably the greatest football player who ever lived, but he is not The Greatest.

Pelé’s silence weighs on him to this day. It becomes the moral focus of this revealing, eye-opening film, and some of Pelé’s teammates and fellow players from the time — Amarildo, Jairzinho, Zagallo and others — weigh in with their own conflicted thoughts. They were teammates and friends, and they remain close to this day. One of them tells the filmmakers he has a hard time accepting Pelé’s silence at the time, even though he admires the man. He points out that a major difference between Muhammad Ali’s defiance and Pelé’s seeming acquiescence was that, in Brazil in 1970, if you crossed the military dictatorship, you were tortured, and possibly killed. Dictatorships are dictatorships. Ali faced prison, but he never feared for his life.

The line between sports and politics is constantly shifting, for good and bad. Just 10 years ago, the idea that Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the national anthem at an NFL game would infuriate a sitting president and cost him his career would have seemed improbable, if not impossible.

The line is shifting back again, thankfully. Sports and politics are inseparable, because at the end of the day we’re all human beings; we all have civic duties and social responsibilities, and human rights and injustice come first. Not everyone agrees, but the cultural ground is shifting.

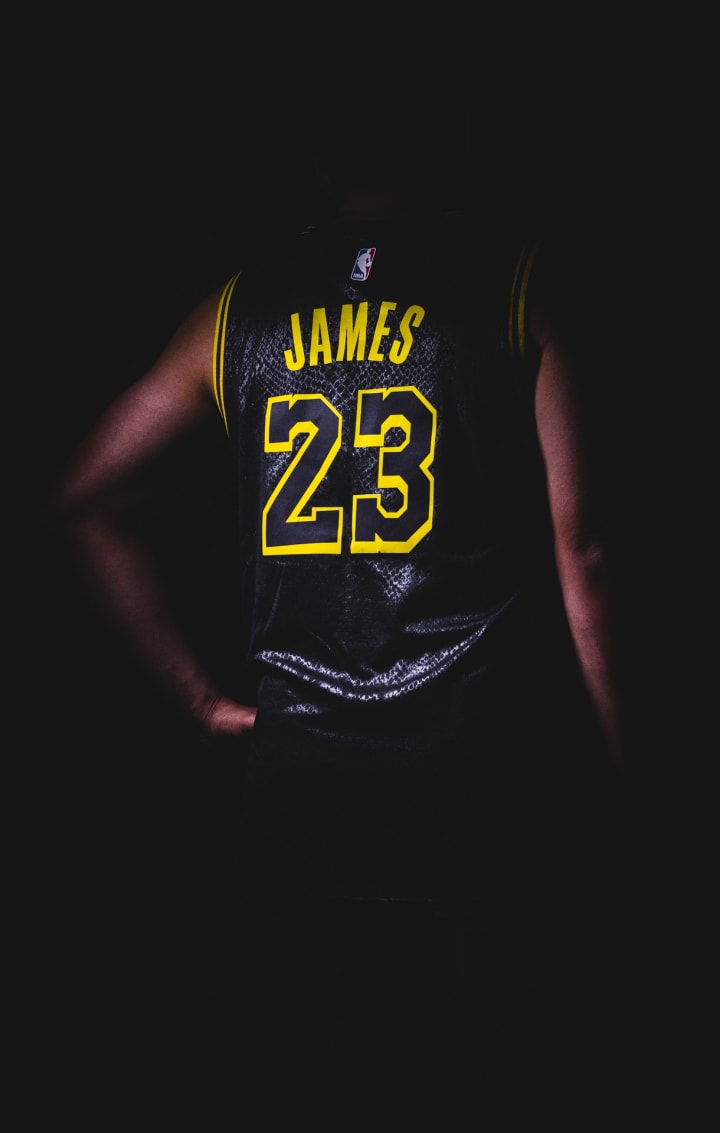

Contemporary soccer legend Zlatan Ibrahimovic said in an interview last week with Discovery+ Sweden that sports figures like LeBron James should not involve themselves in politics, because, “It doesn’t look good.”

“Do what you’re good at,” Ibrahimovic said in the interview. “I play football because I’m the best at playing football. I’m no politician. If I’d been a politician, I would be doing politics.”

LeBron James wasn’t taking it, and this past weekend he hit back. And he hit hard.

“I will never shut up about things that are wrong,” James told reporters, after his LA Lakers beat the Portland Trail Blazers in a game late Friday. “I preach about inequality, social injustice, racism, systematic voter suppression, things that go on in our community."

LeBron James' comments went viral and reverberated around the world after BBC's World News Service picked them up and posted them on BBC News' main website, read everywhere from Azerbaijan to Zimbabwe.

“There’s no way I would ever just stick to sports," James continued, "because I understand how powerful this platform and my voice is.”

Pelé may need a walker on occasion — the result of having been on the wrong end of some really ugly tackles during his playing days, when opponents realized he was too good to stop the old-fashioned way, with skilled defending, and it was easier to simply chop him down — Pelé’s faculties remain sharp.

“The psychological aspects (of celebrity) can really mess with you,” Pelé says in the film.

When asked directly about cozying up to Brazil’s military dictatorship, he replies plaintively, “What could I do?”

Well, more than that, his critics might argue. What would Muhammad Ali have done? What would LeBron James do?

Pelé starts out as hagiography, but it ends as something considerably more. Even if you don’t care much for the Beautiful Game — and if you’ve read this far, chances are that doesn’t include you — Pelé provides food for thought, and is well worth two hours of your time.

About the Creator

Hamish Alexander

Earth community. Visual storyteller. Digital nomad. Natural history + current events. Raconteur. Cultural anthropology.

I hope that somewhere in here I will talk about a creator who will intrigue + inspire you.

Twitter: @HamishAlexande6

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.