Language, Truth and Logic on the Football Field

An open letter to the game's intellectuals

Ladies and gentlemen of the media,

I’ve just about had enough of this, and I can’t be the only one who feels the same. Association football is famously known as The Beautiful Game; yet its language, at least among the English-speaking peoples, must by now have become the ugliest attached to any sport anywhere. I am not referring to the rude words roared at each other by spectators and players alike, of which I myself make liberal use. I am speaking of the technical vernacular of the game itself, in particular the terms used to describe playing positions. These, it seems, have been growing progressively less logical for at least the last half-century. Rarely do I read a match report or other football-related newspaper article without encountering at least one example of their debasement. When I watch a match on television, I am guaranteed several.

Full-back, centre-half, centre-forward; Number 6, Number 8, Number 10 – players, coaches, journalists, commentators, summarisers and studio analysts throw these terms around thoughtlessly, in ways which demonstrate that they either do not know or do not care where they came from. The common fan, trusting that these people know what they’re talking about, follows their habits in his casual conversation about the game. The result is that the terms themselves are increasingly removed from their initial, intelligent meaning; and that what was once the closest thing to a perfectly logical language this side of binary code becomes ever further removed from reality.

This, admittedly, irritates me more than it does most football fans of my generation - partly because I am more informed about the game’s history and partly because, being part-Irish, I am also familiar with a code of football in which the terms full-back and half-back are still used to mean what they say. Nevertheless, if the trend annoys even someone as young and as enthusiastic about the game as myself, it must be far more annoying, and quite confusing, not only to that ever-dwindling proportion of the population which remembers a time in which these terms made sense but also anyone new to the game. When my father first explained to me that when the ITV commentator said “centre-half” he meant “central defender,” my nine-year-old self couldn’t make sense of it. Now, on the rare occasions when my sister joins me for an international match, I wonder what she makes of the language employed by Sam Matterface. She doesn’t ask what he means, and I don’t bother to translate. If I did, I’d probably only confuse her further. Probably, she knows better than to pay attention to the commentary anyway.

Furthermore, the lack of logic in the language to which we have become accustomed may restrict the flow of logic in our thinking about the game – even for our professionals. This may be a fanciful notion, and I wouldn’t dispute that the initial chain of causation runs the other way. The English have historically been reluctant to think abstractly about anything, let alone something as trivial as sport, and this reluctance is a great part of what got us into this linguistic mess. “But,” as George Orwell wrote, “an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.” Is it really so absurd to suggest that the same thing might have happened, and be happening, in the world of football? We came to reflexively call wide defenders full-backs because we were used to seeing them stay back. Now, they advance aggressively in attack, yet our persistence in giving them the wrong name plays its part in leading us to expect the wrong things from them. Is it any wonder that there are few, if any, English coaches among the world’s best? I certainly wouldn’t say that the confused language of our game was a major factor in retarding its tactical development, but it wouldn’t surprise me if it had played some part in the process.

“The point,” Orwell went on to say, “is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly…” I do not wish to say, as Orwell said of the English language, that modern English football in general is declining. The standard of play in the Premier League is as high as that in any league in the world, and our national team is doing better now than it has been doing for some time. But it is doing better in large part because English football culture is overcoming its resistance to thinking. This is a process which is occurring in spite of, rather than because of, the obstacles to logic that its language is putting in its way.

So, let us clear those obstacles as well as we can. For the sake of the sanity of the old, the comprehension of the young, and the future of our football from top to bottom, let’s look at the language we use to describe it. Perhaps we should not be using the traditional designations of full-backs, half-backs and forwards at all. Certainly, if we were to stick to speaking of defenders, midfielders and attackers we would be speaking with more consistency. But this consistency would come at the cost of both elegance and accuracy. When we do use the more modern terms, we obscure two important facts about the game: first, that a player’s position is relative rather than absolute; and second, that attack and defence are determined less by positions on the pitch than by possession of the ball. Not only that, but most of the modern terms do not allow for as much precision as the classical ones without the use of an ungainly number of qualifiers. Purely on literary grounds, “right-half” is a lot less clunky than “right-sided defensive midfield player.” For these reasons, I would consider it a loss if the traditional terms for playing positions were forgotten; but if we are to keep using them, let us at least take the trouble to use them correctly. Before we refer to the positions of the pyramid in a contemporary context, let us map them onto the more modern formation in which a team is playing. It’s usually not as hard as one might think.

Key to Positions

1. Goalkeeper

2. Right Full Back

3. Left Full Back

4. Right Half Back

5. Centre Half Back

6. Left Half Back

7. Outside Right

8. Inside Right

9. Centre Forward

10. Inside Left

11. Outside Left

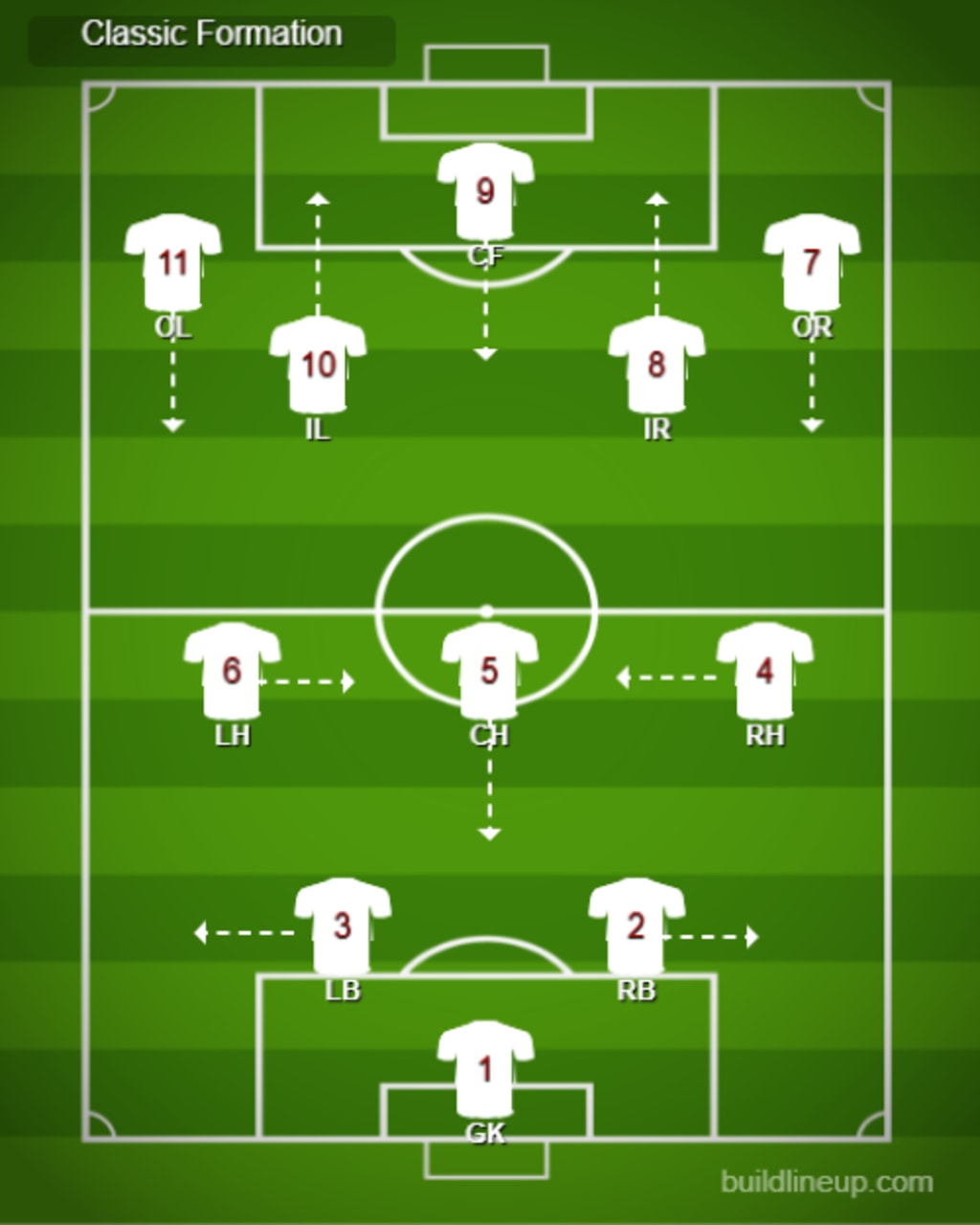

The A-M formation (3-4-3)

This set of positions comes from the pyramid, or 2-3-5, formation that developed in football’s early years and was ubiquitous for decades thereafter. The term “full-back” was invented to describe a defender – someone who played “fully back” from the front line. A half-back played roughly halfway back. So far, so logical. So how did “centre-half” become synonymous with “centre-back?” The answer lies in the reaction to a change in the offside law made in 1925. Previously, passing forward beyond the halfway line was legal only if the most advanced attacking player had no fewer than three members of the defending team between him and its goal-line. The new law amended the minimum to two, making the offside trap harder to employ and leaving the full-backs exposed. In response, full-backs and half-backs began to shift according to the arrows in the diagram. The centre-half dropped deeper to provide extra cover, eventually becoming a third back. As he withdrew, the wing-halves moved infield to cover for him while the full-backs moved outwards. The inside-forwards, who had always had to drop to receive passes, dropped off further to fill the space between the middle and front lines, creating what became known as the W-M formation.

Today’s 3-4-3, frequently used by Gareth Southgate’s England team and Thomas Tuchel’s Chelsea, is very similar. “Wide centre-backs” like Chelsea’s Azpilicueta and Ruediger are not too different from full-backs like George Male and Eddie Hapgood. Between them, Thiago Silva plays the role of centre-back, or withdrawn centre-half if you insist. In the middle, the magic quadrangle of wing-halves and inside-forwards is replicated. The chief difference is on the wings. In the W-M, the outside-forwards were left upfield to concentrate on attack. Reece James and Ben Chilwell, by contrast, shuttle up and down their flanks, taking responsibility in attack and defence equally. When out of possession, they track back, sometimes into midfield and sometimes to positions near their own corner flags, causing the offensive A to envelop the defensive M; but as soon as their team gets the ball, they are off towards the opposition’s end, frequently running beyond their insides to recreate the W-M shape of old. Although they are often referred to as full-backs, they average positions far in advance of the true full-backs and further forward even than wing-halves Kante and Jorginho. If they are to be assigned any position from the pyramid, the best fit is that of a withdrawn wing-forward. (Follow the downward arrows from Numbers 7 and 11.) Thomas Tuchel understands this, even if most British sportswriters appear not to.

The W-W formation (4-3-3)

Calling a centre-back a centre-half makes some kind of sense when one is talking about the central figure of a back three. If one is going to use the pyramid as one’s reference point (and in the twenties and thirties, everyone did), no other position fits as well; and in the W-M, the best of them could still step forward into midfield when their teams had the ball, knowing that their full-backs could cover. Something similar often happens in today’s three-back formations. When Mr Southgate uses a 3-4-3, John Stones reprises the role of Stan Cullis. But it starts to make less sense when three defenders become four.

What happened in Britain, and indeed in most of Europe, was that one of the wing-halves began to follow the centre-half backwards, pushing the full-backs further outward. At first, the withdrawn wing-half, or sweeper, was still distinct from the stopper centre-half, taking on much of his constructive responsibility. When the team won possession, the stopper would hold his position and the sweeper would advance into the half-back position he had vacated. But as the distinction became blurred, and as forward lines became narrower, both centre-backs started to stay back and wing-backs began to get forward more frequently. By now, approximately sixty years after the “flat back four” became commonplace, they have in most cases ceased to be full-backs in any but a nominal sense. What is presented to us as a back four is in practice a back two. The wing-backs flank their centre-backs in defence, marking the opposing wing-forwards, but they frequently advance to support their own wing-forwards in attack. Look at average position or passing network graphs, and you’ll see them more or less level with their holding midfield player, with the central defenders noticeably behind. Liverpool’s Trent Alexander-Arnold and Manchester City’s Joao Cancelo, by moving infield to contribute to build-up play and guard against counter-attacks, have completed the transformation from full-back to wing-half in all but name. The real full-backs are the central defenders, misidentified as “twin centre-halves” by commentators to whom it seemingly has not occurred to wonder what a centre-half is supposed to be at the centre of.

Meanwhile, the attacking centre-half, or pivot, has been revived under their noses. That they have either failed to notice this fact, or forgotten the language necessary to express it, is one reason why discussions about soccer tactics can seem so complicated to outsiders. That a formation with four defenders can often be less defensive than one with three can seem paradoxical. Conceptualise the difference between 3-4-3 and 4-3-3 as that which exists between an attacking centre-half with advanced wingers and a defensive centre-half with withdrawn wingers, and it becomes a lot less confusing. For illustration, we can look to Latin America. There, the classical centre-half never went away; and while British commentators often refer to the midfield pivot as the “Number 4” or “Number 6,” South American national teams tend to give him the Number 5 jersey. In Argentina and Brazil, it was a wing-half who became the third back, with the full-backs shifting to the opposite side, and the other wing-half who later became the fourth defender. The Uruguayans skipped the third-back stage of development, going straight from two defenders to four. Both wing-halves fell back to flank the full-backs, with the centre-half remaining in midfield. In all the fuss about Latin American countries having great attacking full-backs, Europeans have often forgotten that often these players were never considered full-backs in the first place.

This W-shaped defence forms the foundation of most modern formations. With the centre-half sitting at the base of a midfield triangle and three strikers upfield in the centre and wing-forwards, we have a revival of the W-W formation with which Italy and Uruguay won each of the first four World Cups. What starts out as a 4-3-3 in defence becomes a 2-3-5 in attack, as the wing-halves and inside-forwards push on. (This is the advantage of using letters rather than numbers to denote formations: that they can more easily express the elasticity in a team’s shape.) When one inside-forward plays noticeably deeper than the other (Think of Kalvin Phillips and Mason Mount, or Paul Pogba and Bruno Fernandes.), the lopsided W-W is referred to as a 4-2-4, 4-4-2, 4-2-1-3 or 4-2-3-1, depending on how the wingers are classified and how detailed one wants to be. It has often been common for the more advanced inside-forward to play on the left, which is why he is frequently called the “Number 10” and his deeper, more defensive counterpart the “Number 8,” but this is not necessary. By the classical numbering system to which those who use these terms refer, a 10 playing on the right is an 8, and an 8 on the left is a 10. Similarly, a 4 on the left is a 6, a 6 on the left is a 4, and a 4 or 6 in the centre is a 5. Yes, Robbie Savage, I’m talking to you.

Deep Space 9: The M-M (3-5-2), X-W (4-4-2 diamond) and V-W formations

And while we’re on the subject, an 8 or 10 in the centre is a 9; and a 9 playing to one side is an 8 or a 10. The “false 9” is one recent addition to our football lexicon that really has been useful, giving us a handy way to describe a centre-forward who drops off the front to create space for his inside and wing-forwards to exploit. What is less appreciated is that it is possible for a centre-forward to go further still, playing behind some or all of his fellow forwards instead of leading the line. “Centre-forward,” after all, is not synonymous with “striker.” It simply means the middle man in the front five.

Exactly when the deep centre-forward was first used is not certain; but it is known that there was at least one in Argentina almost a century ago, when Independiente deployed Luis Ravaschino at the base of a V-shaped forward line. Tommy Lawton adopted the tactic at Notts County in the late 1940s, and Nandor Hidegkuti pulled the strings for Hungary at Wembley in 1953. The following season, ’54-’55, Chelsea and Manchester City each stole a march on their rivals by copying the Hungarian system. With Roy Bentley and Don Revie as their playmaking Number Nines, Chelsea won the League and Manchester City reached the Cup Final, and Revie was named the Footballer of the Year. In ’55-’56, the advent of the European Champion Clubs’ Cup saw Alfredo Di Stefano inspire Real Madrid to glory. They would go on to win the competition in each of its first five seasons. A decade later, Bobby Charlton, playing between and behind Roger Hunt and Geoff Hurst, was the brains of the England team that won the World Cup.

The deep centre-forward was always a rarity, but he is still out there. Like the attacking centre-half, he never disappeared entirely; and like the attacking centre-half, he is rarely recognised as such today. He survives in disguise in the 4-4-2/4-3-3 diamond formation as a playmaker behind two winger-cum-strikers (think of Kaka at AC Milan in 2005), and in the 3-5-2/3-4-3 hybrid with which Leicester City won last year’s FA Cup. Ayoze Perez may have been described as a “Number 10,” and he did indeed end up drifting off to the inside-left position with Vardy in the middle, but he started the final playing between and behind Vardy and Iheanacho. Manchester United have often used Bruno Fernandes in a similar position, reviving Bobby Charlton’s role; and even in a 4-2-3-1, he has often played more centrally than the most advanced forward, with Antony Martial and Cristiano Ronaldo both inclined to drift to advanced inside-left positions. In 2007-’08, when they won both the Premier League and the Champions’ League, the central figure in their attack often played deeper still. Behind two attacking wingers in Ronaldo and Nani, and two strikers who liked to drop back in Wayne Rooney and Carlos Tevez, was Paul Scholes. As the more attacking midfield player in front of Michael Carrick, he made the team’s rotating 4-2-4 formation seem similar to the long-forgotten V-W, almost replicating Ravaschino’s role. He scored only twice all season, leaving the more advanced attackers to do the running, yet he was the man in the middle who made them all tick.

Not all modern formations are so easy to fit into the paradigm of the pyramid; but if we are to keep using its terms, let us at least make an effort to do so sensibly, being honest about where we run into difficulties. If sportswriters and commentators wait for professional players and coaches to take the lead in this, they will be disappointed. The habits are probably too ingrained in most of them; and in any case, they are not about to give up their own team’s secrets. But those who are paid to analyse the game from the outside would do well to do so in ways that are easy to understand. Football will be a richer game for all of us if we apply to it G.K. Chesterton’s principle on tennis - “that it should be occasionally discussed at least as intelligently as it is played.”

About the Creator

Robert Gregory

Directionless nerd with a first class degree in Criminology and Economics and no clear idea of what to do with it.

Comments

Robert Gregory is not accepting comments at the moment

Want to show your support? Send them a one-off tip.