John Milton's masterpiece Paradise Lost was first published in 1667, in the form of ten books. A slightly revised final version, now divided into twelve, appeared in 1674.

By the time he composed this monumental work, Milton was already blind. At the start of Book Three, as in the sonnet 'On His Blindness' and elsewhere, he makes direct reference to this condition. Certainly here we feel something of the suffering Milton endured. Nevertheless he concludes his autobiographical tangent on a note of resolution, declaring he will look inward to “see and tell of things invisible to mortal sight."

Paradise Lost takes as its main plot the story of Adam and Eve and their banishment from Paradise. The earliest version of this tale is found in Genesis, the first book of the Bible, and is widely known as the Fall of Man. This however is not the only Bible story Milton retells in his epic poem. Through a series of flashbacks and flashforwards he also presents the Creation of Earth, the war in Heaven between Satan and God, and many other key events from Christian tradition. It's been said, and correctly, that for most British people Milton's versions of these stories are now better-known than their Biblical sources.

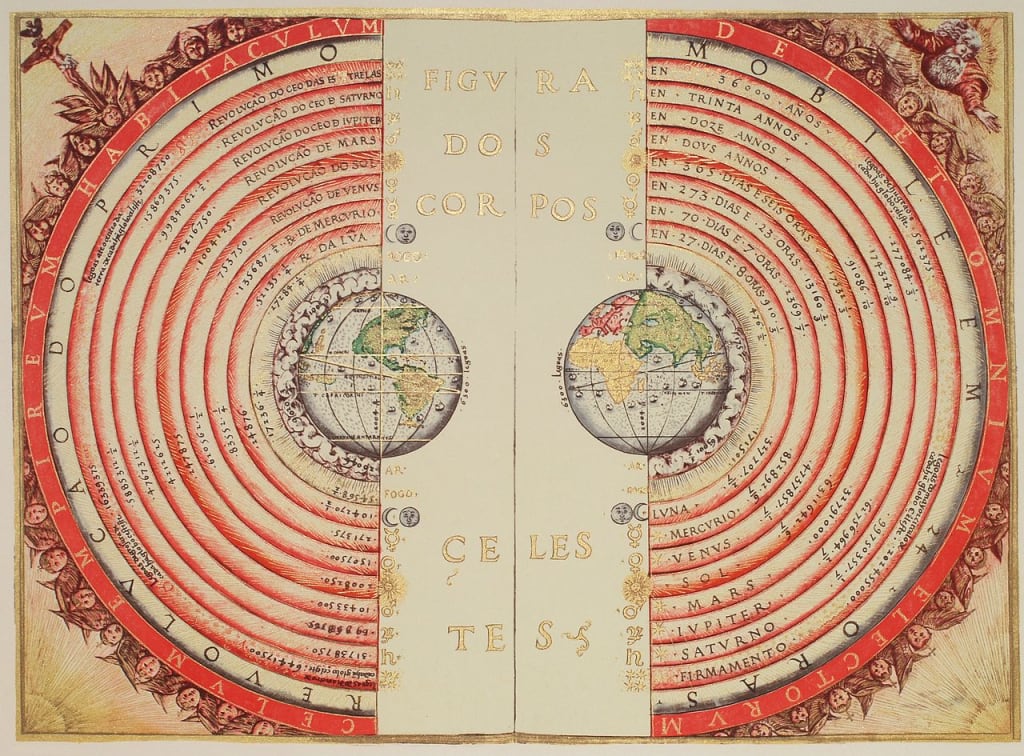

However, to many readers Paradise Lost is more significant for the new elements Milton inserts into this tradition, rather than his retellings themselves. One of the most prominent examples of this is in Milton's depiction of the universe.

Views on this subject had changed radically in recent centuries. The old belief that God set Earth at the centre of the Heavens, and the sun and other planets orbited it, was known as the Ptolemaic model after Claudius Ptolemaeus, a scholar of the Second Century AD. This theory was first disproved by Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543, and later astronomers (including Galileo, who Milton met) further developed Copernicus's work to finally arrive at the more accurate understanding of outer space we possess today.

These discoveries were obviously a heavy matter for Christians, whose belief in the earlier conception of the universe was closely tied to their faith. Milton raises this controversial question (but does not answer it) in Book Eight of Paradise Lost. That same poem however contains astonishing sequences as Satan embarks from Hell and travels to Heaven, the sun and Earth. For the first time in any work of literature these are portrayed as worlds hanging in a void, with vast spaces between them through which Satan must fly. In a way, all science fiction begins with Paradise Lost. It is the very first story in which outer space begins to look as we know it today.

Paradise Lost was written in the aftermath of the English Civil War, with which conflict Milton had been directly involved as a politician and speech-writer. The influence of those turbulent years is frequently felt, for example in the poem's many deployments of military imagery. In Book Two, Milton laments that men:

“...live in hatred, enmity and strife among themselves, and levy cruel wars, wasting the Earth, each other to destroy.”

Additionally, in Book Six during the account of the war in Heaven, Satan and his angels invent cannons to use against God. It's then foretold that in the future, man will commit this same sin.

John Milton was a Puritan, which is the name of a very strict branch of the Protestant Christian faith. Puritans sought a simple life of devotion to God, and usually preached vehemently against decadence and self-indulgence. Milton was therefore religiously as well as politically suited to serving on Oliver Cromwell's Council of State in the years following the Civil War. Cromwell was another Puritan, and this was strongly reflected in the way he ran his English Commonwealth.

It should come as no surprise that Milton was deeply religious, since Paradise Lost is now one of the most important of all Christian texts. The surprising part has rather more to do with the poem's content, and the first of these surprises comes in the character of Satan.

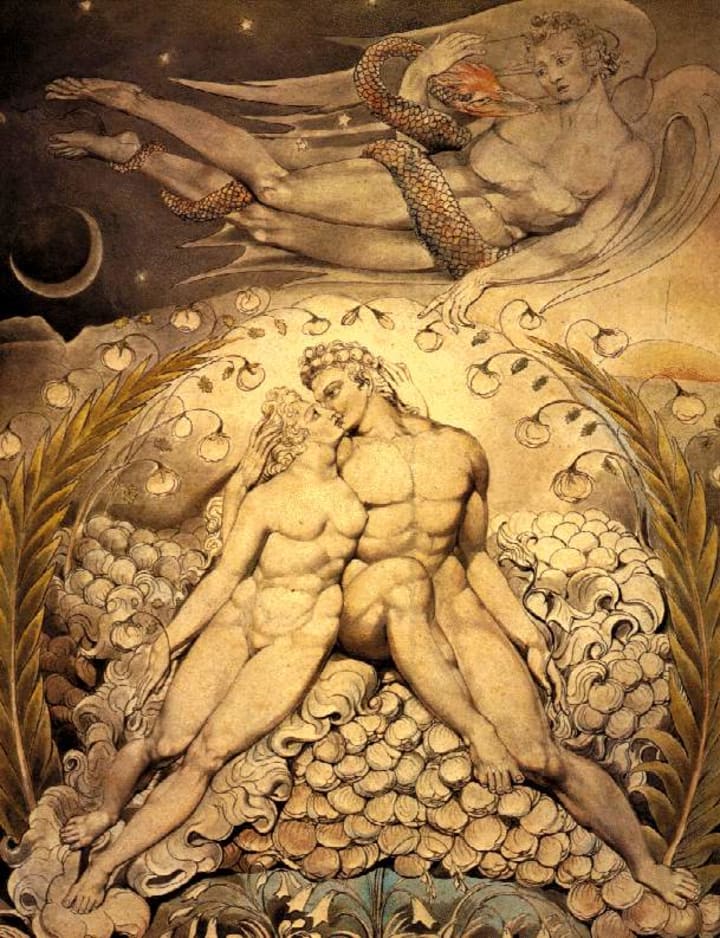

It goes without saying that the Devil himself would be the villain of the story, and that he certainly is, but for many readers Milton's Satan has appeared more of a hero. Certainly, there is much about him to be admired. The Miltonic Satan is a charismatic and eloquent leader, capable also of deep feeling and even a kind of compassion. In addition, some of Paradise Lost's most famous lines go to Satan. “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven” is one of the best-known examples of a sentiment Milton himself did not agree with, but which has struck a chord with countless readers over the centuries. Paradise Lost was enormously popular in the early Nineteenth Century among poets of the Romantic Period, most of whom supported the recent French Revolution, and William Blake argued Milton “was of Satan's party but did not know it.”

This, however, is an example of “presentism” – the way in which interpretations of literary texts are determined by the priorities and preoccupations of the historical periods in which they are read. The Romantics' reading of Satan as a revolutionary leader and hero was not intended by Milton, who actually includes much in Paradise Lost to remind us Satan's authority is unstable or feigned. In Book One, for example, Satan rallies his fallen angles with a stirring speech on how their greatest strength is their trust and solidarity, yet Book Two reveals Satan is in fact deeply fearful of rivals within his ranks. His true motive for personally undertaking the mission to Eden is that he knows his scheming lieutenants will wrest respect and ultimately leadership from him if he allows them to go in his stead. Milton frequently reminds us there's no peace or comfort for those make God their enemy.

What would be striking in any age, however, is Milton's treatment of Adam and Eve's relationship before they taste the Forbidden Fruit and fall from grace. These sections of Paradise Lost contain the very last kind of writing a Puritan would be expected to produce. The lovers' nakedness is described with erotic, sensuous delight. We've barely begun our introduction to Adam and Eve in Book Four before Milton announces: “Nor those mysterious parts were then concealed; then was not guilty shame.”

Of course, this is part of the story Milton is working from, but nowhere else in literature is Adam and Eve's so-called state of innocence portrayed in such openly sexual terms. Milton is emphatic that here he's talking only about “married love.” Once Adam and Eve have fallen, their physical relationship is depicted in a more typically Puritan way. After satisfying their lust, they duly discover “anger, hate, mistrust, suspicion, discord.” Milton's defence of their free-loving previous state, however, is both succinct and convincing:

“Our maker bids increase; who bids abstain but our destroyer, foe to God and man?”

The contemporary advocates of sexual abstinence (who Milton here calls “hypocrites”) were by and large Puritans, which makes Milton's attack on them perhaps most extraordinary of all.

After Paradise Lost Milton wrote a comparatively short coda titled Paradise Regained, then returned to the Bible one last time for his final work, Samson Agonistes. These were published together in 1671, three years before Milton's death.

Many have commented on Milton's choice of theme for Samson Agonistes. The Biblical hero Samson was blind in later life, and ended his days a slave to his enemies. Milton, who had supported Cromwell's parliamentary cause only to live through its defeat in the Restoration of the Monarchy, may for both these reasons have been able to personally relate to Samson. It's a comparison we can make too, for John Milton's literary achievements were nothing short of superhuman. His place in legend, like that of Samson, is assured.

Comments (2)

I read part of “Paradise Lost” in high school, but I don’t remember my class discussing how the time period and historical events may have impacted Milton and his writing. And the idea that this epic poem was a precursor to many science fiction conventions is such a fascinating thought! What an awesome discussion of Milton and “Paradise Lost”! Also, thank you so much for the so, so kind shout-out in today’s Raise Your Voice thread! Jay Kantor let me know to check it out, and I’m so happy you enjoy my pieces!

I have never read "Paradise Lost" because of my nightmarish time studying English poetry at university. I am not sure if I would have the patience to undertake such an epic read, even decades later! With that said, your review is excellent and covers a fascinating range of topics. And of course, using Gustave Doré's drawings is a wonderful addition to your story. I really enjoyed the whole thing. Thank you!