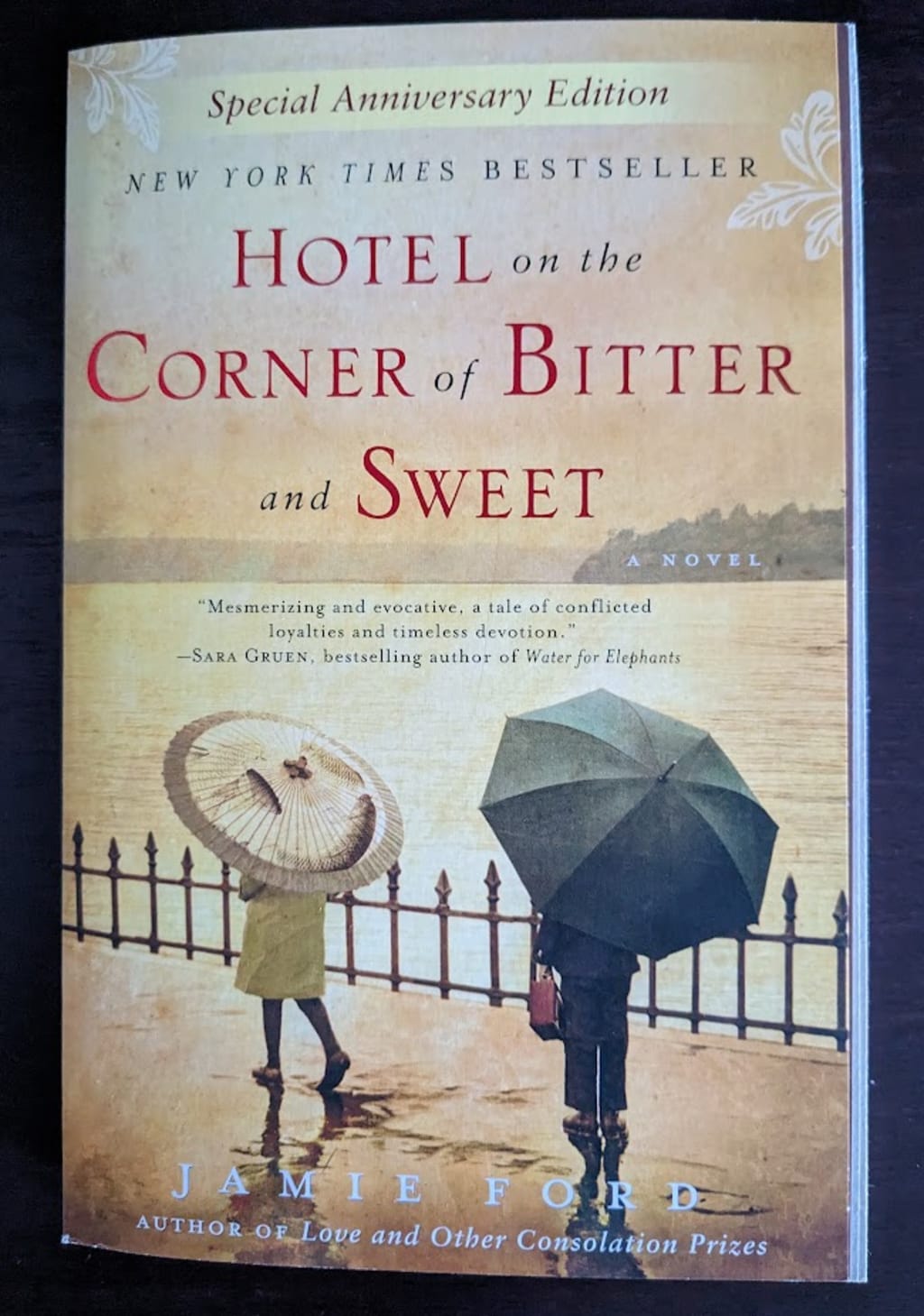

"Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet": A Poignant Coming-of-Age Tale

A review of Jamie Ford's 2009 novel

I don’t typically read historical fiction, but as a Chinese American with family history in the Seattle area, the premise piqued my curiosity. Jamie Ford is a Seattle native and son of a Chinese American father. In an interview featured in the ten year anniversary edition of the book, Ford opens up about the inspiration for the novel. As a child, his father had to wear a “I am Chinese” button during WWII to distinguish him from the Japanese. Ford expanded his original short story until it became his debut novel Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet.

The narrative alternates between past (1942) and present (1986). It begins with Henry Lee, witnessing the reopening of the Panama Hotel where Japanese Americans stored their belongings before they were sent to internment camps. It’s also a place of personal heartbreak — where Henry once waited for his childhood friend to return.

“The more Henry though about the shabby old knickknacks, the forgotten treasures, the more he wondered if his own broken heart might be found in there, hidden among the unclaimed possessions of another time. Boarded up in the basement of a condemned hotel. Lost, but never forgotten.”

In 1942, twelve-year-old Henry lived in his Chinatown apartment with his immigrant parents. His father forced him to wear a “I am Chinese” button, or else risk being mistaken as Japanese. They also want him to stop speaking Cantonese in favor of English. As with many second generation kids, Henry has to navigate these conflicting identities. Although I’ve seen Japanese written in English before, it was refreshing to see Cantonese too, though for readers unfamiliar with the language, the words might not be intuitive to pronounce.

Rather than send him to a Chinese school, Henry’s parents enroll him at Rainier Elementary — a predominantly white school. He’s the only Asian student until he meets Keiko Okabe, a second generation Japanese American. Naturally, Henry and Keiko become close friends despite the racial animosity between the Chinese and Japanese. Henry is also concerned about his bigoted father disowning him for associating with the enemy. If you ever grew up as a minority, you can empathize with Henry and Keiko’s struggles with identity and belonging. It’s also harrowing to see the racism present in the 1940s is alive and well today ranging from playground bullying or through discriminatory politics.

When the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor, the American government orders all Japanese Americans to be relocated to internment camps. Keiko and her family are forced to vacate Seattle. Henry refuses to say goodbye. Through a connection at his school, Henry finds a way to visit. We get a glimpse of life in the camps and the psychological impact it had on Japanese Americans. In the special anniversary edition, Ford includes an interview with a former internee — featured as a child in a photo printed in the book. It’s a fascinating opportunity to hear from someone who lived through a historic and shameful part of America’s past.

Eventually, when Keiko and her family are moved out of state to Idaho, Henry is desperate to stay in touch. His frequent visits to the post office to mail letters and check for Keiko’s replies only highlight the common experience of losing people through distance and time.

“Henry was learning that time apart has a way of creating distance — more than mountains and time zone separating them. Real distance, the kind that makes you ache and stop wondering. Longing so bad that it begins to hurt to care so much.”

Ford writes beautifully, capturing the pain of growing up and growing apart. Henry’s internal conflict is only made more poignant given the larger scale horrors of the war, internment, and racism. For Henry and Keiko, childhood is cut short, no matter how much they try to cling to that innocence.

We see adult Henry living a life filled with regret. Recently widowed, his grief lingers and mirrors his childhood loss. Ford also explores the theme of owning our stories. The Panama Hotel presents the opportunity for Henry to confront his past and remember. When we acknowledge our own experience — all of it including the bitter along with the sweet — we can see the possibility of closure.

If you have any interest in Asian American history, or like poignant, coming-of-age stories, Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet is sure to resonate.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and the Amazon Associates Program. If you purchase this book through these links (Bookshop.org or Amazon.com), I will earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you!

Originally published on Medium

About the Creator

J. S. Wong

Fiction writer, compulsive book reviewer, horror/Halloween fan. Subscribe if you like stories on writing, books, and reading!

Follow me on Medium: https://jswwong.medium.com/

Follow my Wordpress blog: https://jswwongwriter.wordpress.com/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.