English Literature in the Eighteenth Century

By Doc Sherwood

Eighteenth-Century English literature was by and large written according to a principle called neoclassicism. The main argument of this position was that the classics – that is, the writers of ancient Greece and Rome – had already perfected the art of self-expression. The duty of the modern author, therefore, was simply to imitate them as closely as possible. Individual imagination and personal insights were therefore not considered as important as skill and accuracy in the emulation of classical styles.

Although neoclassicism was based on ancient philosophies and ideas, these were often freely reinterpreted or expanded upon. Comparatively little of the classical time remains available to us, and neoclassicism frequently reconstructed its source material from just a few surviving fragments. As a result, many neoclassical dictates are in fact wholly Eighteenth-Century in origin.

During the Eighteenth Century a movement of intellectual liberation, dubbed The Enlightenment by German philosopher Immanuel Kant, characterized much European thinking. In many ways a continuation of Renaissance humanism, Enlightenment philosophies stressed the potential for constant human progress through the propagation of rational and scientific principles, while rejecting superstition and religious dogma. The Industrial Revolution and the independence wars of America and France, all of which occurred in the Eighteenth Century, were seen as a culmination of Enlightenment ideals. Literary neoclassicism, with its privileging of rationality, clarity and order, can likewise be understood as part of this so-called “Age of Reason.”

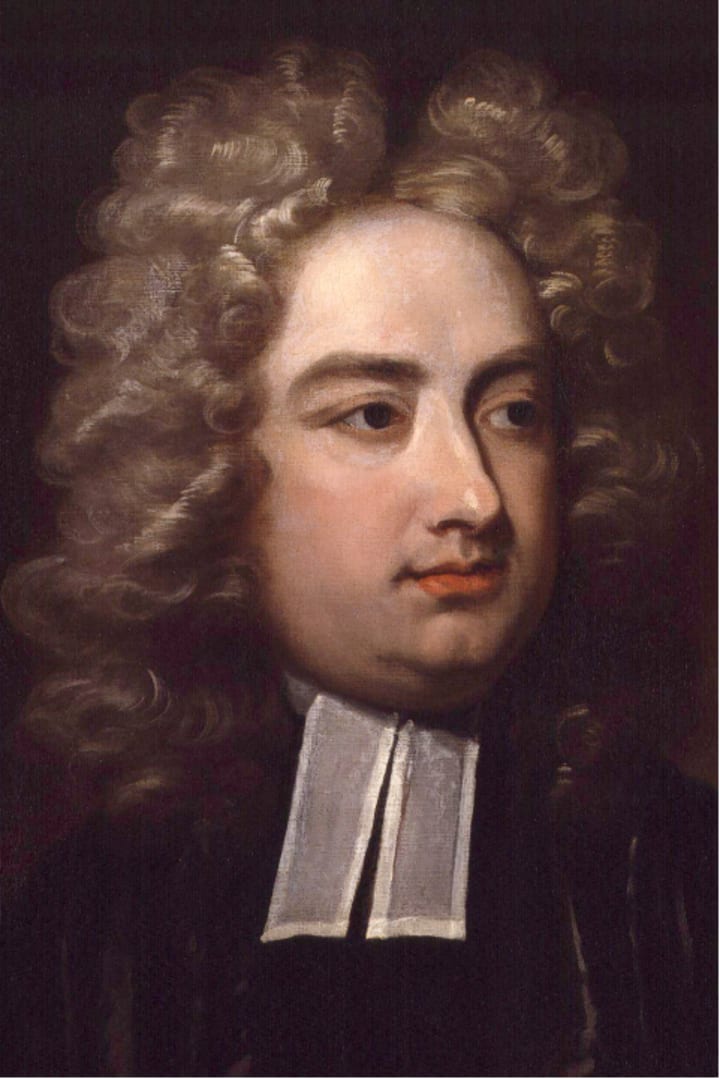

In British literature the years from around 1697 to 1745 are called the Augustan Age, after the reign of Emperor Augustus Caesar. At that time lived the greatest Roman poets, Virgil, Ovid, Horace and Propertius. The English and Irish poets John Dryden, Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift are known as Augustans because they modelled their own writing on the works of these Romans, and sought in particular to imitate their talent for the epistle and the satire.

These Eighteenth Century writers recognized too that at a time when the British Empire covered half the globe, London had become an imperial capital just as Rome was in antiquity. The Augustans hoped therefore to create in their contemporary London a sophisticated literary world of the kind Rome had known.

The metropolitan coffee-houses were hotbeds of fashionable gossip and political intrigue. King Charles the Second, who had lost his father to civil war, actually tried to ban these establishments for the dangerous revolutionary sentiments he imagined they fostered. Even if his reaction was somewhat excessive, the coffee-houses certainly welcomed customers from all walks of life, and the Augustan writers found rich material there for inspiration. Le plus ce change, c’est le plus ce même chose – how many of you Vocal writers today can function without coffee?

The period is not one usually associated with successful English drama, and indeed many had come to feel the theatre was in a pitiful condition by the Eighteenth Century. Directors of that time were even known to bring onstage the Ghost of William Shakespeare or Ben Jonson, who would then complain about the state of things! Nevertheless, a small number of Eighteenth-Century plays are now considered significant works of English literature. One of these is The School for Scandal by Richard Sheridan, published 1777, but the most enduring work of Eighteenth Century theatre is surely The Beggar’s Opera, written by John Gay in 1728. An early Twentieth Century German version of this play by Bertolt Brecht, Elisabeth Hauptmann and Kurt Weill, retitled The Threepenny Opera, is now a much-celebrated standard of musical theatre and film.

Poetry, however, flourished in the Eighteenth Century. Prominent literary figures include Dr. Samuel Johnson, who wrote the famous poems ‘London’ and ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’ and in 1775 also published one of the most important and influential English-language dictionaries. Thomas Grey in 1750 produced ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’, which for many years was considered the greatest of all English poems. Meanwhile in Scotland, Robert Burns was establishing his reputation as that country’s national poet with such works as ‘Auld Lang Syne’, which remains the anthem of New Year’s Eve to this day.

One other significant literary form arrived in Britain in the Eighteenth Century, and unlike the others it did not have any precedent in classical writing. That form is the novel, or extended fictional prose narrative. Novels today have replaced poetry and drama as the most prominent and lucrative mode of publication, but the genre began in Europe in the early Seventeenth Century, and from Spain and France made its way to England.

John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678-84), though it is not usually considered a novel as such, still made an important contribution to the development of a native English style for producing long and intricate stories in prose. The question of which was the first English novel has been much debated. Samuel Richardson wrote Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded in 1740, and Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749) is also significant. Both these men are grouped among the earliest British novelists. Jonathan Swift also achieved permanent fame through this new literary mode, with his satirical masterpiece Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

The novel generally considered England’s first, however, is Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719). Although enduringly popular in and of itself, boasting what is surely one of the best-known and most-loved plots in all literature, this book is also monumental merely for bringing the English-language novel to the fore. It’s funny to think that in Shakespeare’s time, if you could claim to be a court poet, you were set for life. A question I like to cynically ask my students, which if anything may be all the more apposite here on Vocal, is which would you rather be today – poet or novelist? Which one are you more likely to brag about being when you’re in the pub? And which one sounds the surer route to a comfortable income? If we wanted to argue Eighteenth Century English literature changed the world of writing, I myself would be hard-pressed think of a more persuasive example to close on!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.