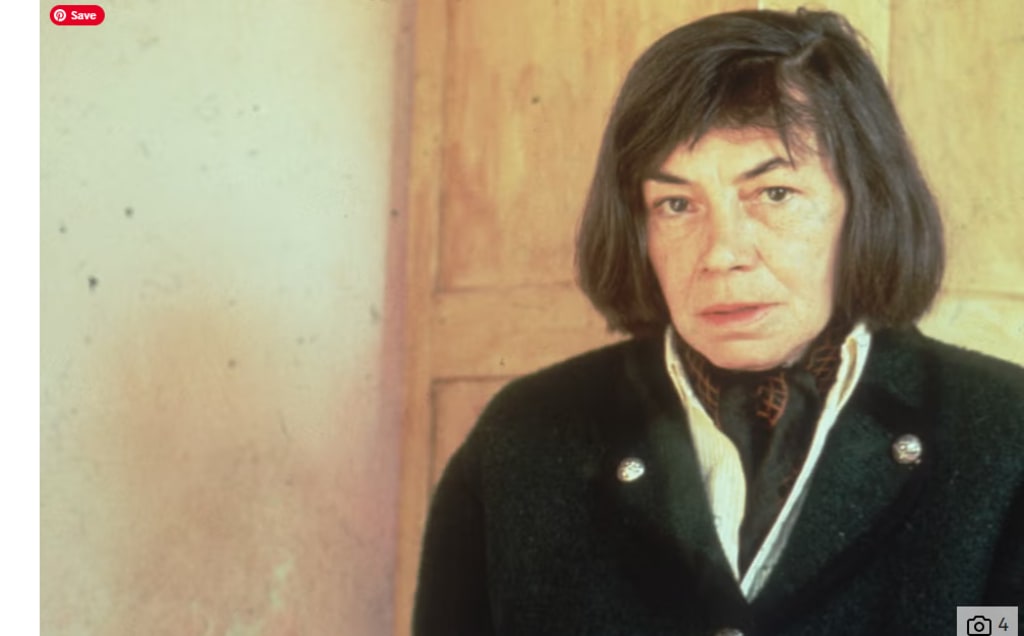

"A murder is a form of intimate bonding": The peculiar life of Patricia Highsmith, the writer of The Talented Mr. Ripley

Patricia Highsmith established the standard for contemporary psychological suspense novels. Tom Ripley. Katie Rosseinsky looks back at a literary icon with a dark side.

Someone like Patricia Highsmith wrote about antiheroes. Consider Tom Ripley, the "suave, agreeable, and utterly amoral" conman who is the main character of her 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley. He travels over Europe by lying, cheating, and killing people, but he manages to win our sympathy in the process. Even over 70 years after he first appeared on the page, he is still incredibly captivating, which is why Ripley, the Netflix TV adaption starring Andrew Scott, is one of the most eagerly awaited films of 2024.

Like Ripley, many of the protagonists in Highsmith's books are completely normal-looking people driven by evil impulses, terrible secrets, and a constant fear of being discovered. It's not surprising that early admirer Graham Greene dubbed her "the poet of apprehension" after reading them; reading them can seem like reading the literary equivalent of an anxiety attack.

In addition, Highsmith had a (very) dark side that extended far beyond her drinking, odd habits like carrying snails in her handbag, and fascination with the darkest recesses of human nature. Her characters could be fascinatingly horrifying. Who was this odd person who was fixated on studying the thoughts of murderers? And how did she end up creating the model for contemporary psychological crime fiction?

Highsmith, who was born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1921, had a difficult upbringing. Ten days before she was born, her parents got divorced. Mary, her mother, subsequently revealed to Patricia that she had consumed turpentine while pregnant in the hopes of losing her unborn child. The relationship between the two would be marked by this tendency towards performative harshness.

When Mary married Stanley Highsmith in 1924, the young Patricia adopted his last name. A few years later, the couple moved to New York City, but they had acrimonious arguments and split up frequently.

Patricia would remember her childhood as "a little hell." Mary left the 12-year-old kid in the care of her grandmother in Texas after abandoning her without any prior notice or explanation, lasting a whole year. Patricia carried bitter memories of the episode for the rest of her life, and she would later find Freudian parallels in her personal life. She wrote to a friend, "I repeat the pattern, of course, of my mother's semi-rejection of me." "I never moved past it. I therefore look for ladies who may similarly harm me".

She began writing short stories while attending Barnard College in New York and attempted to sell them to magazines. She appeared to have discovered the perfect topic matter right away. "I'm good at building suspense," she wrote in 1942. "I find the macabre, the harsh, and the strange fascinating." Highsmith was an avid journaler who left behind almost 8,000 pages of handwritten notes describing her daily activities. Her notes were written in a disorganized variety of languages, some of which she struggled to speak, which is unfortunate for her long-suffering archivists.

Her diaries from this time are a wild ride. She writes with self-awareness, "I have an arrogance that I shall never lose - that I don't want to entirely," while bragging about her own brilliance in one moment and criticizing herself for not working hard enough in the next. She describes a rotating cast of largely female love interests (she does have male admirers, too, but she writes that "kissing them is like kissing the side of a baked flounder") and her ongoing battle with hangovers from drinking too many martinis. These mostly transient infatuations are dotted with periods of self-loathing, which seem to be caused by internalized homophobia.

She would break off her lovers when they grew too close, purposefully ruining both her own and other people's relationships. She was "a lesbian who did not very much enjoy being around other women," according to her friend Phyllis Nagy, the screenwriter who would go on to win an Oscar for adapting Highsmith's Carol for the big screen.

She worked as a publicist for a deodorant company for a short while before spending a longer time writing comic books. Truman Capote recommended that she attend the Yaddo writers' retreat in upstate New York, where she met Stan Lee of Marvel Comics. Here, she contributed to Strangers on a Train, which was eventually released in 1950 to widespread acclaim both critically and commercially. The following year,

It established the pattern for the iconic Highsmith book: two characters who are pulled together uncontrollably by guilt and obsession, and a plot full of heart-stopping tension. However, the author would momentarily veer off course for her next project and write a romance with elements of autobiography.

Highsmith first began visiting a therapist in her late forties. She'd slept with a number of the women in her social circle who were beginning to settle down and get married. It was time, she decided; her friend the English novelist Marc Brandel was persistently making marriage proposals, and therapy seemed to be the way to "get myself into a condition to be married," she wrote.

In response to her therapist's suggestion, Highsmith thought she may have fun wooing a few married women who were "latent homosexuals" by attending a group session. The writer began working shifts at Bloomingdale's to pay for this. A beautiful blonde wearing a fur coat walked into the toy department one December day, bought a doll for her daughter from Highsmith, and went home to sketch out the story for The Price of Salt, which became Carol after Todd Haynes's stunning film adaptation starring Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett. Not long after, she quit going to the therapist as well.

In the book, the younger, ambitious designer Therese and the older, married Carol begin a romantic relationship after this brief encounter on the shop floor. It was published under a false name, and Highsmith didn't identify herself as its creator until a few years before her passing. It is the only one of her books that doesn't contain graphic violence, but that doesn't mean it's a light read—it's still filled with realistic details.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.