'The orchestra will never die': Why one composer says we need live music now more than ever

Tomas Videla, a composer who has worked on the soundtracks of some of Hollywoods biggest films believes we need music to feed our souls right now

They say music feeds the soul. And now more than ever it's something humankind craves and needs. As the world copes with the enforced incarceration thanks to the coronavirus epidemic, thankfully, composers are still out there being creative and making music. And while a lot of the entertainment industry has come to a grinding halt, some are lucky enough to still be working and making money.

Thankfully, for the rest of us, Tomas Videla is a classically trained composer who has worked with some of the best in his industry.

He says music is what can keep the world going in these turbulent times. Tomas interned with renowned composer Theodore Shapiro, who created the scores for movies, Bombshell, and Last Christmas.

He also recently contributed to the music for the Apple TV film The Banker, starring Samuel L Jackson, which he collaborated on with award-winning composer Scott Salinas.

Tomas says: “Now more than ever we need music. As a composer, I am lucky because there is still a necessity for what I do. For musicians, it is harder.” Tomas counts himself lucky to have worked on some great movie projects. One of his most recent was as an orchestrator for the upcoming Al Pacino flick, Axis Sally, which is in post-production. Directed by Michael Polish, it’s based on a book by William E. Owen.

Tomas says: “There is nothing like a full orchestra. But how can they get together and play at the moment? It is not possible. We must have music in these times to uplift us.”

The good news is, despite the current situation, Tomas believes we, as human beings need the passion and beauty that you get from a group of people playing in unison: “There is nothing like it,” he says.

“Yes, we have the wonders of modern technology. But you cannot layer the sound in the same way. There is a beauty about it which cannot be recreated.”

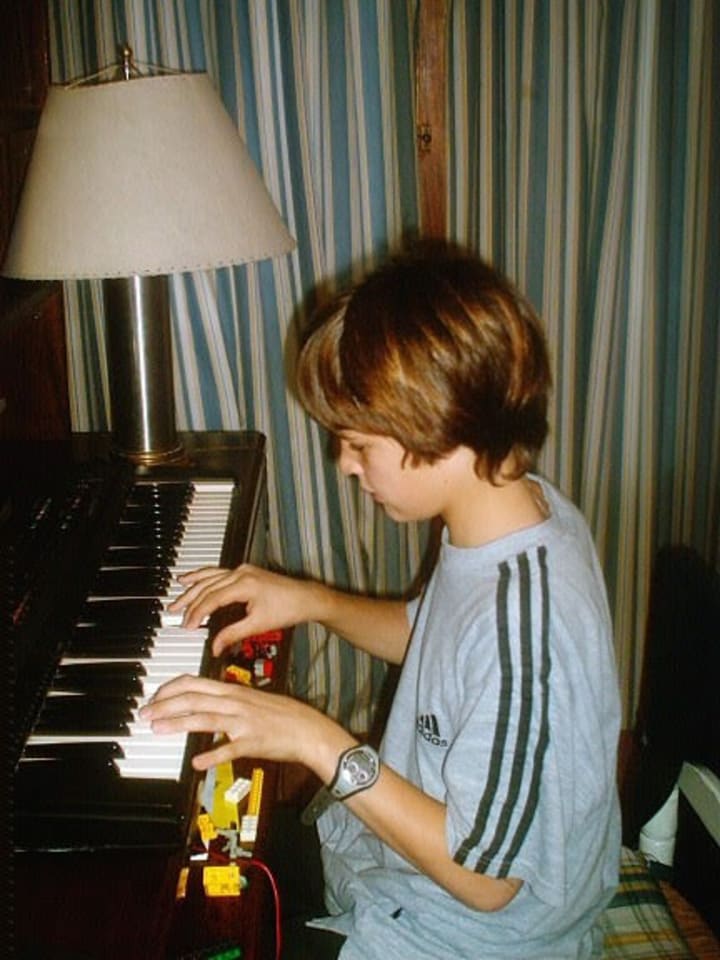

Tomas, who grew up in Buenos Aires has loved music since he was a child. “I've always been into music pretty much,” he says. “I cannot think of a moment in my life where I didn’t say to myself, ‘I'm going to be a musician.’”

He was three years old when he first picked up an instrument: “I had a guitar that my dad bought me,” he recalls. “He put fishing-line strings on it.

“We went to church, and I would sit next to the people playing songs and copy them.”

Tomas, now 27, was brought up on a diet of Argentinian folk music. As well as becoming accomplished at the guitar, he was also pretty nifty with the bombo legüero, which is a percussion instrument.

His parents, Ana, a teacher, now in her 58, and father, Nicolas, 61, an agricultural administrator made sure music was part of his childhood. However, when Tomas was ten years old he discovered The Beatles: “I even had the hair. It was awful!

“We had a big book with all the Beatles songs, in sheet music. “My brother started teaching me a little bit of piano and then I would take the songs, I would be like, ‘I love this one from the Beatles. That was how I learned to read sheet music.”

It was how Tomas developed a passion for the piano. By the age of 10, he has got into playing Queen as well, another favorite,: “For a while, it was the guitar, and piano, I couldn’t decide,” he recalls. "When I finally made my decision to pursue a career in music, I told my parents. They were understandably concerned, as they wanted me to have a steady and reliable income. And that isn’t something you can usually rely on. However, they knew I was stubborn. And they realized when I went to study in the US, I was completely dedicated to making it work. So they gave their blessing.”

Tomas started to look at the scores of movies and found himself inspired: "Up until that point, I was thinking, ‘I'm going to be in a band. It's going to be great because of The Beatles.’ Then I heard the soundtrack to Pirates of the Caribbean and the Chronicles of Narnia. I remember I was about 12 years old, in a mall with my mom and my gran, and it changed my life. I was like, ‘I want to do that.' I thought to myself, ‘Oh my God, this is amazing.’”

By the age of 16, he began to concentrate jazz, tango and film scores: “I thought to myself, ‘I like being in the background. I don’t want to be center stage. I like the thought of being in the shadows in a way. Because I'm kind of shy so I don't like being exposed or anything.’”

He adds: ‘A lot of my friends wouldn’t know who John Williams is. But if you hear ET or hear Jaws, you know that soundtrack immediately.’ And that appealed to me. That's when I decided I wanted to be that kind of composer – someone who is known for their work and sound.

“So I started watching films. Even films I used to watch as a kid, I rewatched them, paying attention to music. This whole new world just opens in front of my eyes I never knew existed. That's when I decided like, "I want to do that. How am I going to do that?"

Tomas begged his parents to get him a teacher. Despite his mom and dad’s opposition, they reluctantly agreed, and he started to work with Nessy Muhr. An incredibly accomplished pianist, Nessy was a musical prodigy. She played at the Teatro Colón, the biggest theater in Argentina.

Tomas says: “She taught a lot of people and was amazing. I studied classical piano with her for three years. When I finished school, and I told my parents, ‘I'm going to study composition.’ I think they were worried I was going to be impoverished and have no money!”

However, his parents need not have worried. Tomas had a great mentor very close to home – his uncle Nico Posse. An accomplished Argentinian composer and pianist, Tomas worked with Posse on his operatic adaptation of an Argentinian classic, the Martin Fierro, and in Hay Otra Cancion. They also collaborated for the San Isidro Film Festival and his latest album Memorias Urbanas.

Thanks to his incredible ability, Tomas was accepted to Columbia College in Chicago, which has one of the most prestigious Masters programs in film scores in America.

Having worked on several musicals, which included Aida, The Count of Monte Cristo, and Yo No Soy Amy, a musical based on the singer Amy Winehouse's life, Tomas was able to win a scholarship. The college was also impressed by his arrangements for the Orquesta Sinfónica de la Policía Federal – he created a number of pieces for their performances.

“I was sad I never saw them myself” Tomas reveals, “But I was told they were very well received!”

In 2017, Tomas moved to Chicago and started his studies with Kubilay Üner.

He also had the opportunity to work with Sebastian Huydts, the head of the music department.

Tomas was in the New Music Ensemble as part of his employment at Columbia.

“It was a happy accident,” reveals Tomas. “I told Sebastian, ‘I want to conduct, I want to do all of this. And he said, ‘Great, you're going to be conducting rehearsals when I have meetings.’ I thought he was going to forget. But then I got a call, and he said, ‘I have a meeting right now. I cannot go; you need to conduct.

“I was surprised and pleased. I thought it would be a one-off. “But then it happened again.

“Soon, Sebastian was asking me to conduct for him. Even dress rehearsals before concerts. It was an amazing opportunity.”

Tomas began to work on bigger and bigger projects. He worked on arrangements of La Muerte Del Angel (Astor Piazzolla), Danaza Del Trigo (Alberto Ginastera), and Conga Del Fuego (Arturo Marquez) – all arrangements that he created and conducted for the New Music Ensemble.

Tomas also lent his talents to arrangements to the film scores of To Kill A Mockingbird and Saving Mr. Banks.

The challenge in the projects was the New Music Ensemble wasn’t the run of the mill orchestra. Sometimes there would be two pianos and three guitars and no cello. Tomas had to work with whoever was there. And he had to sit down with the musicians individually to make the effects work on the arrangements.

Tomas says: “It was a challenge to recreate the same emotions and mood which were in the original pieces. However, that kind of work good challenge and stretches your creativity.”

Tomas came to finish his Masters to Los Angeles in 2019. He now works as a composer, orchestrator, and conductor. Despite there being a lot of technology now involved in the process of creating film and TV score music, real musicians are still integral to the finished result: “The orchestra doesn’t need to be in the same room now.

“For example, you can record strings one day, and then record the brass and percussion the next. But there are still people who do it the old way, the whole orchestra in the room.”

This is Tomas’ favorite way to work: “I love that because I love conducting. And there is nothing like the sound of everyone playing together in unison. It helps the music, and it helps the musicians. Everyone is feeding off each other's energy. And I believe the end result is much better.” Tomas also recently worked on an IMAX documentary narrated by Morgan Freeman – Into America’s Wild: “I jumped on that and did additional writing, collaborating with Scott Salinas," he says.

“We recorded the orchestra in Bratislava. This is what you can do these days. We did a remote session. So we're here in LA , and they record in Bratislava, and Morgan Freeman narrates. How great is that?”

Tomas also had the opportunity to attend the Los Angeles Film Conducting Intensive in January this year. He worked alongside Angel Velez, Conrad Pope, and William Ross.

He recalls: “I loved it. It takes you out of your comfort zone. We composers are used to being locked in a room in front of a computer all day. And this was completely the opposite - every day conducting a different ensemble.

“It sounds kind of stupid , but you get to see music from a different perspective - at least a viewpoint where we as composers are not used to seeing it, which is the performing side of it. And it makes you ask yourself all these questions that maybe when you’re sitting in your studio writing, you don’t ask yourself. It didn’t only help me as a conductor, but also as a composer and a musician. I loved every single second of it.”

He is now working with award winning composer Michael Kramer on some of his current projects. Tomas says it was a privilege to work with such an accomplished composer: “He’s an amazing person and a great mentor. I’m constantly surprised by his creativity - he comes up with ideas and sounds that I could never think of. It really makes you step up your game and be on his level, so you end up learning a lot.”

Tomas believes you have to work for your art – not that it strikes you: “I always remember Kubi Üner, one of my big mentors, saying: ‘Inspiration is for amateurs. You don't wait for inspiration to hit you. You just sit down and write,’” he says.

“The people who say: ‘Oh I'm waiting for the inspiration to hit me.’ That’s bulls**t. It doesn't happen.”

Tomas believes for the moment, the orchestra won’t be made redundant. But it might happen: “We're not recording as much stuff,” he says. “We're doing everything on the computer.

“But you need to be able to mimic an orchestra, and you need to make it sound believable. And it’s a trap a lot of composers can fall into – thinking the sound is the same.”

He adds: “I've heard a lot of mock-ups and they fall into a fake computer sound. It's awful. Nothing beats a real-life orchestra. Nothing beats 60, 80, 100 people in a room playing together. You won't get the emotion. You just won't.”

However, it can be an ongoing battle for composers, working with directors. To get them to want to go with a real live sound.

Tomas says: “They're not musical first, usually. And they've often heard the music so many times that the moment you put a different version in front of them, they can spot it. They will sometimes say, ‘I'm not sure if that.’ That's where the orchestra or conductor comes in, and you just give a note. Then they play it again, and the director says, ‘Oh, I love it.’ And you just changed one thing.” And with that one small change, you make the director happy. And that’s when you know you’ve done a professional job.”

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.