History of The Who

Partly because of their unlikely longevity and partly because they stayed on the road more than any other British band, The Who has paralleled rock and roll's musical/cultural development.

The crowd outside Boston Gardens on April Fools Day 1975 was psyched beyond the normal craziness attendant to rock events. Cars couldn’t move through the densely congested pedestrian traffic radiating from the arena’s entrance, across the street and halfway up the surrounding blocks. Clear bottles of Miller and brown Narragansett were smashed indiscriminately on the sidewalks and street in random patterns, kids stood in clusters outside the old men’s bars while the regulars muttered approvals. Under the El in a psychedelic bath of flashing neon heavy-lidded, red eyed freaks hawked t-shirts, bootleg records, mushrooms, weed, and scalped tickets.

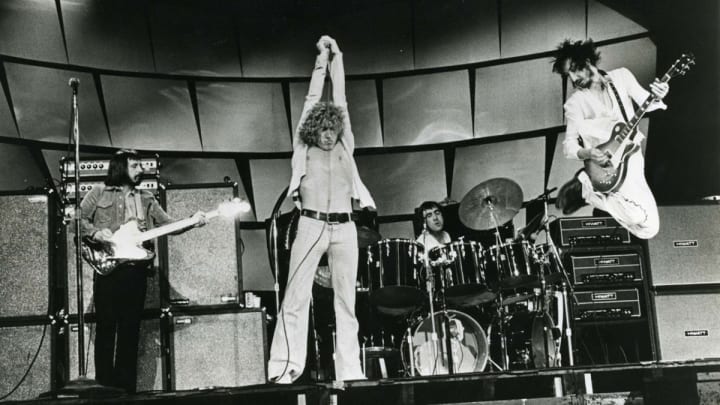

The buzz that kept this whole scene hopped up just short of overdrive was The Who, one of the greatest rock and roll bands in the world. Originally Boston was the first stop of this American tour, but Keith Moon collapsed at his drums halfway through “I Can’t Explain,” ending the set before the first song was completed. A near riot was quelled when the makeup date was announced on the spot for April first, making this the last show on the tour. Many fans on hand for the show, knowing Moon’s reputation for self destruction, seriously doubted that he was still alive, or that the group would stay together following the tour.

By now this sort of speculation was as rampant as Beatles reunion queries back then. Rumors of The Who's imminent dissolution, prompted by incessant punch outs on stage and off, lasted over a decade after they made their first impact in England. But they stayed together, without a personnel change, longer than any of their peers from that English Invasion following the initial popularity of the Beatles and Rolling Stones in early- to mid-60s.

Partly because their unlikely longevity was characteristic of rock and roll insanity, but mostly because they've stayed on the road more than any other British band of their time, The Who has paralleled rock and roll's musical/cultural development during their existence as a band and as solo entertainers, evolving from lowly but ambitious beginnings to full-fledged iconic stardom. This process was exemplified by lead singer Roger Daltrey's early days as a street fighting high school dropout whose greatest kicks came from rock and rolling all night in London pubs to his rise to Hollywood sex symbol.

But the success of the Tommy film came at the expense of the original idea. Most Who fans were incensed at the way the band's masterpiece concept album was dragged through a pretentious "rock opera” controversy, a paradoxical situation that gave them mass popularity but undercut their credibility with rank and file rockers.

"The only thing that matters," Daltrey insisted during Tommy's theatrical run, “is that as far as we're concerned, we're still the scumbags we always were. That's what I liked about the fact that we played Tommy at the Metropolitan Opera House, everybody missed the point about that. The fact that a bunch of scumbags like us were at the most posh place in America playing rock and roll, that was what was important. We got through that door and got up on the stage and did it. We're probably one of the most scumbag groups you could ever wish to lay your fuckin' eyes on, and all these geezers can say is whether it's a bloody opera or not. Which I thought was the least important thing about it, who gives a fuck whether it is or not? We've been kicking the shit out of each other ever since we started."

At first Daltrey played guitar in a band called The Detours that built up a following in Roger's home territory, Shepherd's Bush, driving weekend dances at local pubs with a hard nosed rock and roll stomp and a reputation for playing stinging versions of the most popular current material. Pete Townshend, who at the time played banjo in the same traditional jazz Dixieland band as John Entwistle, recalls that "Of all the bands at school, The Detours were the best. Roger was the best guitarist, a very basic guitar player but very confident and very fluid in a way. I can only think of how I remember him, but he struck me as having in those days the same sort of quality that George Harrison had. He could learn something, parrot fashion, then make it sound very fluid.”

Roger didn't start singing until Entwistle and Townshend joined his band and Pete took over the guitar playing. The name changed to The Who while Townshend introduced blues songs to their act and local followers became more fanatic. After an audition with Philips Records their original drummer was fired and they used a series of session drummers until one night when a drunken Keith Moon stormed onto the stage and took over, destroying part of the session drummer's kit in the process. He was hired instantly. The Who was persuaded to change their name to the High Numbers in an effort to identify them with the Mods, a youth separatist movement among Britain’s newly adolescent war babies based around a cult of sharp clothes, fast cars or motor scooters and a penchant for amphetamine "purple hearts," which were great impetus for all night bouts of drinking and fighting.

After one single, "I'm the Face," they changed back to The Who, but the connection with the Mods had already been established. At the insistence of new managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, Townshend began to write songs for the group, and over the course of a few months the Who became the hottest new band in London.

Several factors contributed to their early success. They were the loudest, flashiest, most dynamic band around, their management did a tremendous job of promoting them to the English media, and Townshend's songwriting was remarkably good. Their first three singles—"I Can't Explain," "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere," and "My Generation"—became instant anthems for working class teenagers. Their stage shows became the stuff of rock legend as word of the intense maelstrom of sound climaxed with wholesale destruction filtered over to the US. Townshend explains, "At the time our live act would be the three records that we had, a few cuts off the album and a lot of Tamla / Motown stuff. We used to open with "Ooo Poo Pah Doo" and close with a long, drawn out version of "Smokestack Lightning" with me doing lots of feedback, banging the guitar about and switching the switches and occasionally, when I could afford it, smashing a guitar.”

"Going to America is what kept The Who together," claimed Daltrey, whose penchant for fighting nearly got him thrown out of the band just before "My Generation" became a hit in England. Every British rock band knew that the key to lasting success was to make it in the States, a virtually endless market where a recognizable cockney accent is worth at least ten grand a night. By contrast, a band could become quickly played-out in England, where there were no more than a dozen or so outlets once you graduated from the pub circuit. Despite their phenomenal rise in England, The Who was deeply in debt—their promotional budget and bent for destruction accumulated bills much faster than the limited amount of money to be made at home could cover them. They began their assault on the American audience in 1967 as part of the second wave of the English Invasion, along with Cream and Jimi Hendrix.

Although The Who was already an underground legend when they arrived in the States to play Murray the K's Easter Show at the Paramount in New York, a concert in Detroit, the only city in America where "I Can't Explain" was a hit and the Monterey Pop Festival. They failed to reproduce the meteoric rise to the top they enjoyed at home. Their American record company, Decca, gave them little support and the band was left with only their galvanic live performances to win over the vast American audience. Between the instrument smashing at the end of each show and hotel smashing afterwards, the band was burying themselves so deeply in debt it was doubtful they'd ever work out of it. But adversity worked in their favor by giving them a common goal to fight for—if they'd made it right away, as Cream and Hendrix did, the friction between group members and the pressure of being on top most probably would have broken the band up. Even as it was, their first few appearances were as notable for the onstage friction the band generated as for what they sounded like. A line from "My Generation"—"I hope I die before I get old”—became their calling card as the piled-up rage and frustration was blown off night after night in their concerts.

About the Creator

Will Vasquez

Venue manager in Austin, TX. No, you can't meet the band.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.