Creator Spotlight: Dane BH

"Learning that I wasn’t at the mercy of my own creativity’s whim, but had some agency in the matter, was a turning point [in my writing career]." -Dane BH

Dane BH is a published poet and author based out of Massachusetts. A spiritual thinker and homey writer, Dane invites her readers in with somehow-familiar phrasing and prose. Like some of the greats, her work expresses the observations we know we've made, but just couldn't convey.

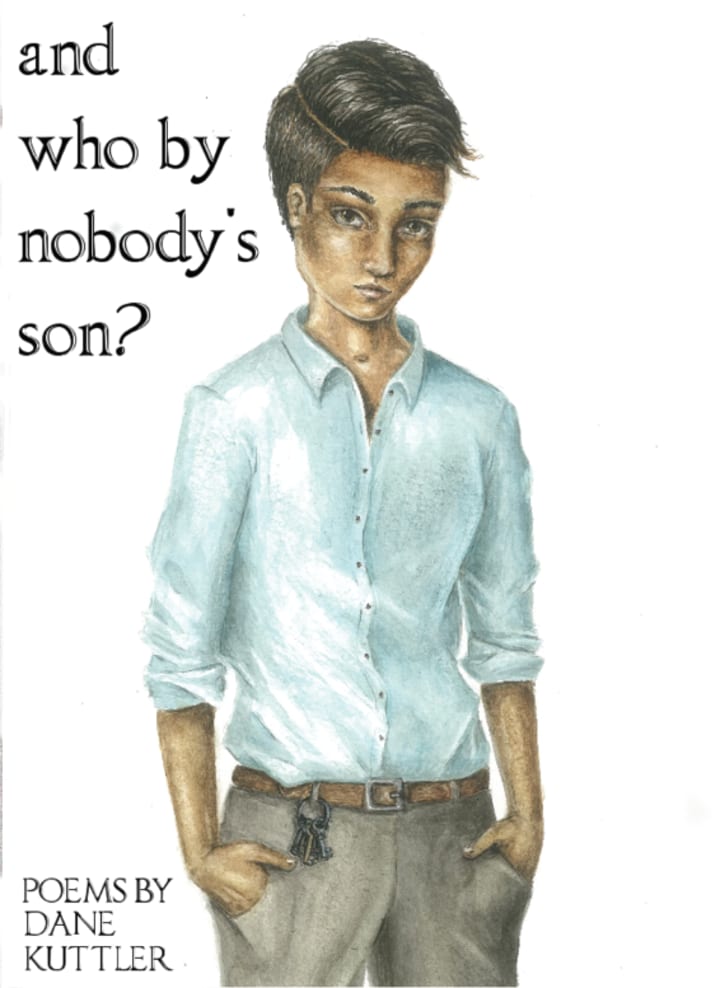

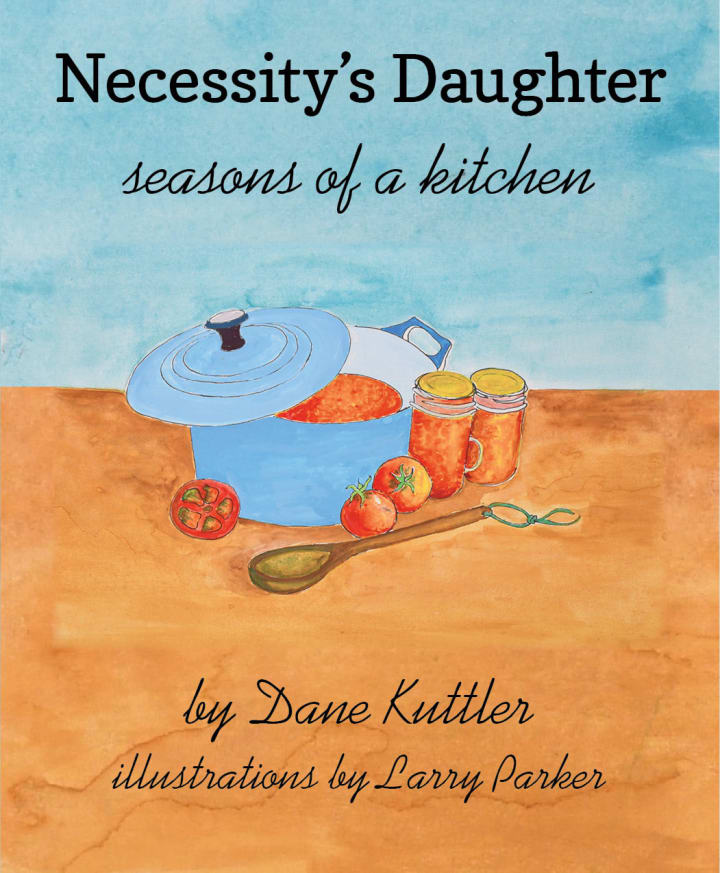

Her first book of poems, And Who By Nobody's Son?, in which poems "draw on the language of Yom Kippur liturgy, Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), and queerness in pop culture," was released on Choose the Sword Press in January 2016. Her latest book, Necessity's Daughter, "the literary equivalent of something cozy and sweet," was self-published in 2021 and represents the beginning of the next phase of her writing career. These two books, along with many others in between, are available now on her website.

The native New Jerseyan has toured nationally three times, performing her work in concert halls, libraries, and living rooms all the same. She's won the Best of Blood and Thunder award for her poem, “This is how I want to die,” and she's made quite an impression on us at Vocal as well.

Dane's claimed first place in our Vocal+ exclusive Deep Dive fiction challenge with her piece "Things We Know About Sharks," and placed third in two more challenges: the Summer's Day poetry challenge with her sonnet "spit," and the Remarkably Real challenge with her piece "I Swore I'd Never Get Married. Then I Had Ten Weddings."

We couldn't be happier that Dane found a home for her creativity and success here on Vocal. Without further ado, please welcome Dane BH to center stage in this #VocalSpotlight. Enjoy!

On Her Interests, Character, and Spirit:

I’m at my happiest when the table’s full and the house is warm. Writing is my art; advice and explanations are my craft; cooking is my love language. I’m bossy and loving; I say the wrong things loudly; I love TV discourse and read reviews of every show I watch, preferably episode-by-episode.

I make pickles and my own chicken broth; I love sea shanties and mining songs; I sing high alto and like harmonizing more than I am good at harmonizing. I teach cooking classes over Zoom; I love public speaking more than most people hate it; I prefer mountains to oceans. I’m queer; I’m synesthetic; I’m Jewish. Repetition is holy; so are onions and salt; most things I say are prayers.

On Her Life as a Poet:

The first poem I ever wrote was in the third grade, so I’m not sure it was a decision, exactly, except maybe one to do my homework. But by middle school, I was filling notebooks and slipping them to my English teacher, who wrote very kind notes in the margins about my oversized feelings.

In high school, I fell in with a crowd of kids who lived for the open mic nights at our local coffee shop. I’ve always loved public speaking, but those years taught me how to handle a microphone and an audience, and gave me a space to try new things.

At the same time, I was falling in love with competition and slam poetry. I never made it far in slam, but I kept competing for years and volunteering at major competitions. I made one of my best friends in the slam world; though neither of us compete anymore, we still critique each other’s writing with the same sense of supportive, earnest honesty that comes from trust built over years.

In 2010, I decided to write a poem every day for a year. I wrote a lot of truly bad poetry, and learned a ton. In the last ten years, I’ve written 30 poems in 30 days each April and November - April for National Poetry Month, and November in solidarity with my novelist friends trying to crank out their NaNoWriMo projects. I still write a lot of really bad poems! But I never regret doing the long stints—there’s usually at least one thing in there I wouldn’t have written without the whole exercise. A number of my poems on Vocal got their starts in my April/November sprints.

Choose the Sword Press, now sadly defunct, published my first collection of poems in 2016. I’ve self-published four books since then. All four have been collaborative efforts; at least half a dozen people have had a hand in each book. Those collaborations have been the highlights of my writing career.

On Key Moments in Her Writing Career:

In the tenth grade, a slightly-older friend of mine in the same poetry class melodramatically sighed and let her head fall to her desk because she had writer’s block. We were all used to it. Since (she declared) she couldn’t possibly do any writing that day, she offered to critique and edit some of my recent poems.

We spent a pleasant hour digging through some of my work, and when we were done, she looked at me and intoned, “Don’t ever stop writing. You can lose your writer’s eyes. I know, because mine are gone. Forever. The way you see things, the way you put them down—it can all disappear. I’m telling you. Don’t ever let this happen to you.”

She did figure out how to write (brilliantly, actually) again. But for all that I knew she was being a drama queen, she’d put words to one of my biggest fears, and the message sank in. For the rest of that year, every time I went a few days without writing something, I panicked, grabbed a notebook, and started scribbling. It’s probably what helped me grow most as a writer that year.

In the eleventh grade, my English teacher challenged us to write a term paper centered around an original idea about a piece of literature. It was a ridiculous ask—she was used to teaching graduate students. I chose DH Lawrence and wrote five pages about his poem "Peach." She read my argument and told me she’d seen similar points made in real academic writing about Lawrence. I thought she was telling me I had to start over; instead, she congratulated me.

She told me I was in good company, and to, “Never stop digging just because you’ve discovered a famous literary critic in your hole.”

The moment stuck because most of my English teachers up to that point had been largely nurturing and admiring—I had talent, and I was a voracious reader, and I’d always gotten praise for my writing. Without tearing me down, she made me realize I wasn’t alone in either my talent or my dedication to the craft. She was, in a way, welcoming me into a much bigger community of writers.

In the same vein, around that time, an older cousin of mine, an established writer, offered to look at some of my poems. I sent her a packet of maybe a dozen, waiting for the inevitable praise I’d become accustomed to. She took me out to lunch and handed me the printouts. There were notes EVERYWHERE. She dove into my poems and took them seriously. She had plenty of good things to say, but she made it clear that her bar for me was higher than the ones at school. Once I got over the humbling part, I was full of awe and gratitude. She, too, treated me like a community member instead of a precocious child. Today, she and I trade essays and stories, and she listens to my critiques as seriously as I do hers.

(In that same tradition, when a younger cousin of ours began sharing her poems with me, I too, welcomed her to the community of writers by taking her seriously. She often joins me for my 30/30 sprints now—and watching her grow as a writer has been one of my life’s joys.)

Another moment worth remembering: during that year in which I wrote a poem every day, I started writing a novel-in-poems around the beginning of April. It was a way to keep from having to come up with an entirely new idea each day. I’d heard famous writers talk about listening to their characters before, but it had never happened to me. I was stunned the first time one of my characters clearly spoke to me—and she was NOT happy with something I’d written.

Writers talk about flow, a state of being totally absorbed in the work. That’s what allowed me to hear those characters—and working on the novel through the course of that year let me practice entering that space deliberately. When I sit down to work on a new piece, I spend a minute stepping into that mindset. For lack of better words, I let my focus soften and try to listen, letting my brain reach for whatever in the ether feels like talking today. It’s actively seeking inspiration, instead of waiting for it to strike. Learning that skill—learning that I wasn’t at the mercy of my own creativity’s whim, but had some agency in the matter—was a turning point.

That’s not to say I never get writer’s block! There was one November where every single poem I wrote was terrible. Not one gem in the pigpen. It was humbling as all heck, especially since my good writer friend, who also does a 30/30 exercise, was having an absolutely fabulous month, turning out brilliant little gems every day. That said, I wasn’t afraid or discouraged. After eight years of doing 30/30 sprints (and my one 365/365) I knew I’d get back to the river, that flow state, eventually; I just had to keep writing. I’d accepted how possible and necessary it is to keep writing through the blocks, seeing it as a legitimate part of a good writing process.

On Finding Meaning in Stories After They're Written:

My piece "Unfixable Things" was a response to Vocal’s Green Light challenge prompt during the Summer Fiction Series. At first, I was just focused on the setting—a food pantry—and getting the details right so the reader would feel like they were there with me. It wasn’t until I was almost finished that I realized the piece had become a container for my frustrations about the world.

The world isn’t just an unfair place, but an unkind one, especially if you’re poor. I think a lot of us fantasize about fixing or rebuilding the world in a better way, but much of the time, there’s only what’s right in front of us. We’re locked, like the main character, into generations-long cycles of survival where escape is fantasy and coping is the goal. Revolution’s not even in the picture. And the main character’s not even the one eating out of the food pantry—she runs the place. She’s as stuck as her clients are. Finding moments of softness, compassion, real connection and humanity in spite of that? That’s everything.

On the Reality-Based Core of Her Work:

Like every good lie, everything I write is wrapped around a kernel of truth. Whether or not you can see that kernel is a function of how well you know me, but I’m not sure it matters. I care more about whether the piece sparks some truth in you.

On Developing Her Writing Style:

I like to think that as I get older, my writing gets bolder. At least, I hope it does. One of the most important critiques I’ve ever gotten was a few years after college, when someone I respected told me my writing was, “holding its breath.” Learning to write badly was one part of learning to breathe. But the other part is learning to write into what scares me, instead of dancing around it with pretty scaffolding. That part, I’m still learning.

On Her Book "And Who By Nobody’s Son":

Your first book of poems is easier than the second because your first book gets to be drawn from the ten or twelve or twenty years of poems you’ve written throughout your life. Your second starts from scratch after that.

"And Who By Nobody’s Son" was definitely that first-book experience - combing through years and years of poems, figuring out themes and ideas, then massive amounts of revision and editing (at least two poems in that book retain only a single line from their original drafts.)

I was actually stunned by the process of getting it published. I’d self-published four chapbooks—printed and stapled by yours truly—before that, selling them at national poetry slams, but mostly trading them for other poets’ chapbooks. The idea that anyone else cared about printing my poems—to the point of footing the cost for printing them, let alone paying an artist and an editor to work with me!—was revelatory. I felt so lucky and valued.

On the other hand, someone once said being the world’s newest published poet is a little like being the world’s greatest Frisbee Golf champion—there is a very very small group who cares a lot about who you are and what you do, and no one else has heard of you. It’s delightfully humbling.

On Her Book "Necessity’s Daughter":

Necessity’s Daughter is a big departure from other books I’ve written and published. About five years ago, some friends and I decided we were going to have dinner once a week. Zoom notwithstanding, we’re still going. The group has grown and changed over the years, but its core remains warm and bright. One of those friends is a farmer; they bring us leftovers from the field, heaping crates of vegetables from June through November. I use the veggies for our dinners, often feeding up to a dozen of us. (In pandemic times, the farmer drops crates of vegetables on my porch, and we wave to everyone through the window as they pick up their share for the week.)

The book is a love letter to them, plain and simple, but also to my relationship with food and seasons. I’ve used Facebook posts to keep track of things—when did the cucumbers hit their peak last year? Which summer had the drought that killed the tomatoes? When did we start getting butternut squash? The book captures that sense of season and cycle.

It was also a community effort. One member of that group (named Hobbit in the book) did the book’s layout and design; my father-in-law did the illustrations and paintings. We started working on it in December 2019, and it came out in spring of 2021; it was one of my biggest tethers to community during long periods of isolation.

On Who Inspires Her to Create:

Around the beginning of the pandemic, I started talking with an old writer friend of mine almost every day. We were the sort of friends who could talk once a year and pick up like we’d never stopped—and that was how we were for a long time. But since we got into this mess, she’s been a lifeline for me.

She is one of the best writers I know. She’s funny, which I am not. She’s taught me everything I know about horror movies, and, thanks to her, I can give you a critical analysis of at least one movie I can’t bring myself to watch. She gives me advice like, “Make it more awesome,” and asks tough questions like, “Why is this essay?”

But in all seriousness, she inspires me to be more awesome on the daily; to fish out the absurd, spotlight it, and make it dance. When I read her work, its fearlessness sparks me, pushes me to be braver. Even the horror stories. Maybe especially them.

Her name is Lindsay King-Miller, and you’ll be glad you followed her on twitter.

On Her Goals as a Writer and Poet:

My biggest goals are these: keep writing. Don’t stop.

On Advice to Amateur Poets:

One piece of advice: look for unconventional places to publish. I got to publish a poem in a medical journal once. That was a highlight for me; I love it when poetry offers people a different way to consider their own areas of expertise.

On How Becoming a Vocal Creator Helped to Develop Her Online Presence:

I’ve been really enjoying Vocal’s Challenges, because they push me out of my little poetic hobbit hole and into a much more adventurous writing space.

I’ve done very little to monetize my writing overall (poets are pretty used to not getting paid for like, anything, ever) and Vocal’s incentives (bonuses and the like) are pretty novel for a poet like me.

On Her Favorite Stories She's Published on Vocal:

Well, all the fiction I’ve ever written is published on Vocal, which is pretty cool. I literally did not write fiction until the start of the Summer Fiction Series. That’s one of the things I love about the way Vocal has expanded my range. My favorite fiction piece is probably "A Murder and a Funeral," which makes sense because it was the last of the nine I wrote that summer.

My favorite poem that I’ve published on Vocal is definitely "Hermione Granger Claps Back." It’s got roots in my history with slam; I wrote it very much as a performance piece and would love to be able to share it in live performance someday.

Don’t think about it—first thing that comes to mind:

What is one thing you couldn’t live without?

Good kitchen knives

Favorite Musical Artist?

Favorite Albums?

Freedom Highway, Rhiannon Giddens;

Blue, Joni Mitchell;

Karov, Batya Levine; and,

Who’s Next, The Who

Favorite Movie?

Cloudburst, an indie flick about elderly lesbians who break out of a nursing home and go on a road trip to Canada.

Favorite Poets?

Amanda Gorman’s new book, Call Us What We Carry, just knocked me on my ass.

Patricia Smith’s sonnet crown "Motown Crown" from Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah still haunts me.

Rachel McKibbens will crucify then resurrect me between first line and last.

Airea D. Matthews, whose students I envy.

Favorite/Most Impactful Poem?

"Peace and Justice," by Tara Hardy. Don’t expect the same answer in five minutes, though.

Cats or dogs?

Dogs

Favorite travel destination?

Mountains with water, where even the dirt is clean.

Day or Night?

Crepuscular times - twilight and dawn.

What’s your go-to late night snack?

Cheese. If I have my druthers, something aged with a lot of crystally bits.

What are you currently binge watching?

Ted Lasso and Star Trek: The Original Series

What are you currently reading?

Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer

If you could speak a new language, what would it be and why?

I regret not learning Spanish when I could, but honestly, I’d want to speak Hungarian because it’s one of the world’s most isolated languages, linguistically; it doesn’t have easy brethren like the Romance languages do.

Nobody from Hungary expects you to speak Hungarian. I want to see the look on a Hungarian’s face when they realize I can speak to them in their mother tongue.

Favorite story you read on Vocal by another Creator?

I have a soft spot for this story; the writing’s excellent, but the line, “I dream in English,” reminds me of something my grandmother, an immigrant for whom English was her fifth language, told me. She said she only knew she really belonged in her new home once she started dreaming in its language. This piece absolutely nails the soft cacophony of being in a new and foreign place.

Last note: special thanks to Call Me Les for both her services to the community of Vocal writers and for her help with this Spotlight!

Closing

Thanks for chatting with us, Dane! While we don't mean to promote fear within the Vocal Community, we do see some validity in your tenth-grade friend's advice:

Don’t ever stop writing. You can lose your writer’s eyes.

Our writing represents the connection between creative visions and reality. Without it, we're left ruminating on the greatest short stories, poems, and novels that never were—the greatest literary moments that were never read. The less we write, the more blurry that connection becomes. While you can transcribe this vision, you owe it to the world to be vocal.

If you're as big a fan of Dane's work as we are, be sure to subscribe to her Vocal author page and frequent her website for upcoming tour information, a collection of her published work, and more!

Thanks again, Dane!

About the Creator

Vocal Spotlight

Vocal Spotlight aims to highlight standout creators who are changing the world one story at a time. We're getting to know the storytellers who inspire us the most, and we can't wait for you to meet them.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.