Lost and Found in Dharamsala

Accepting discomfort, learning a new culture, and fitting in while far from home

It’s boiling hot when I walk out of the airport. My internal systems are all jumbled up, recalibrating after the end of a spin cycle. It’s dark, it’s 8:30 PM, and it’s a humid 90 degrees. There is noise everywhere: people talking, people shouting, PA announcements, cars honking. My legs are cramped from the thirteen-hour flight and it feels amazing to stand, even if it means lugging around my comically massive suitcase.

When everyone finds their bags—all much smaller and more sensibly packed than mine—we walk to the hired cars waiting to take us to our hotel in New Delhi for the night. In the morning, we will load up again and drive another thirteen hours north to Dharamsala, the capital of the Tibetan exile community, deep in the Himalayan foothills in the province of Himachal Pradesh. But tonight, we can just sleep.

I don’t know anyone else in this group yet. Most of them go to the same university as me, but we are scattered across many majors, years, and departments. There are some from other schools too, and the first night is an exhausting flurry of introductions, icebreakers, and brief orientations.

As we get settled in our shared rooms, I can’t help but compare the amount of stuff I brought to that of my classmates. Most of them packed in trim, portable backpacking packs, but I have a gargantuan rolling suitcase, a day pack, and a shoulder bag, each one filled to the brim. My suitcase was over the 50-pound limit when I checked in in Cincinnati, and I had to pull everything out in a tear-soaked whirlwind. I packed my fears for this trip, and it’s showing. I’m self-conscious and nervous. I don’t sleep well.

In the morning we wake early. We load our baggage into a fleet of white vans. The program leaders—Kari, Simon, Annie, and our lead teacher Geshe Lobsang, known to us as Geshe-la—explain to us the schedule, when and where we will take breaks, and they warn that the trip can get a bit bumpy.

Thus prepared, we depart.

India smells like fire and life. Driving on the highway, with the windows down, we see the white-hot sun rising through a hazy screen of clouds. I chat with my new classmates in the car, getting to know them and why they are there.

Zameer, who speaks Hindi, sits up front and chats with the driver. He tells us about some of his favorite Bollywood movies and Indian music. I have never been anywhere like this before. I listen to everything, without really absorbing it. I wonder what I have gotten myself into, and what is about to be.

The flat, fiery plains start to turn into hills. The road gets rougher. I feel a creep of nervousness coming up my spine, and I try and fail to push it down.

There is so much distance between us and New Delhi now, and between New Delhi and Newark, and between Newark and my home and my family in Kentucky. Now, if something were to happen and I needed to get back, it would be a long drive and a long plane ride to get to the familiar. I am on the other side of the world and nine and a half hours ahead of everyone and everything I know. I don't know any of these people. They don't know me. Where am I? Who am I?

Finally, mercifully, the car ride ends and we get out at Sarah College, home of the Institute for Buddhist Dialectics and the venue for the Emory University Tibetan Mind and Body Sciences Summer Program. It’s a small cluster of multi-story white buildings oriented around a temple and a courtyard. Stepping out of the van, the air is immediately cooler, though still warm. To my left, in the distance and hovering over the hills, I can see the faint line of the Himalayas.

We are welcomed into the cafeteria. There is a hand-written sign outside by the door that reads TASHI DELEK - WELCOME TO YOU ALL, and the staff and a few teachers are waiting to greet us.

We walk inside and are met by a cool blast of air and the smell of tea, served hot and with cream and spices in little cups. We are each presented with a silky white kata scarf, a traditional Tibetan symbol of compassion that is used in various ceremonial events, including as a welcome to arriving guests.

We are assigned to shared rooms, two to a room. My roommate is a year below me. She has a positive, upbeat energy about her. We lug our bags up the stairs—or rather, she carries hers relatively easily, and I lug mine–and enter our room, which is right next to the classroom that we will be using for the duration of our stay.

We set to unpacking, while chatting in the manic way that one does when they are meeting someone they don’t know but will live in close proximity with for any major length of time. Her unpacking goes quickly, and mostly consists of her taking out her few clothes and spreading them on the shelf, then kicking her empty bag under her bed.

Meanwhile, my suitcase erupts into piles of T-shirts–cotton T-shirts, heaps of them, stacks of them–various pants, long skirts, and dresses, books, bags, toiletries, and–God help me–photos. Actual print photos. A whole box of them, along with a photo clip mobile that I had packed, in its original box, at the bottom of my suitcase. I start taping photos to the wall. The faces of my friends, family, and dogs look out at me from the wall and from the ceiling, suspended in the air above my bed.

Although I am rooming with another American student from my university back home, and although most of my classmates are white and from a similar background as me, we are surrounded by a totally different culture from the beginning. We wake up early and meditate in the temple with the monks before breakfast. We talk with them at meals. Our classes begin a few days after our arrival: one on Buddhist philosophy and religion, and the other on traditional Tibetan medicine and healing. We sit in the classroom on velvet-cushioned sofas. The sun comes streaming through the windows, and the room becomes sweltering.

For the most part, I adjust fairly well those first few days. I am enamored with the initial excitement of being somewhere so foreign and getting to know my classmates.

But then the panic hits.

One day, our program leaders reveal to us that on one of the weekends, we will be going to a mountains for a hiking trip. Ostensibly, this is an exciting revelation. Most of my classmates are thrilled.

I am not. This trip is planned for the weekend of my birthday. If we are in the mountains on my birthday, I won't be able to Skype with my mom. I have never been away from her on my birthday before.

All at once, the sense of that massive distance strikes me like a punch to the gut. I feel winded and afraid. I don't want to be severed from my connections back home. I try to keep the tears under control. I feel like I'm going to throw up. The idea of not talking to my mom on my birthday is unthinkable. I can't shake the dread.

I suffer through the next week. During the day I meditate, eat breakfast, go to classes, talk to people, and generally enjoy the experience. But at night or during breaks, I call home. I resist the tenets of Buddhism we learn in class. I am on the defense, like everything I encounter in India is intentionally trying to rip my home, my family, and my faith from me.

So this, then, is homesickness: Gravel in the stomach. A feeling of heavy emptiness where comfort should be. Gut-wrenching, painful longing.

Dharamsala is fire-brown, thangka tapestries, Tibetan, Hindi, maroon robes, mangoes, dumplings, chai. Home is grass-green, wet, church, family, chicken, American English, iced tea. Instead of seeing the beauty in where I am, all I can think about is where I am not, and how much I want it back.

---

The classroom is sweltering. There are fans, and the windows are open, but it’s not doing much. The smell of Dharamsala wafts in: that ever-present burning scent, mingled with the cool mountain air.

Our first assignment is to write an introduction about ourselves and to share it with the class. We are asked to think about our stories, our journey, and what brought us here.

A couple of people go each day. I wait and listen. I don’t really know what to say.

Some of my classmates' stories are simple, others more complicated. Some are placid, others traumatic: loss, grief, assault. Many people share stories about their families. Others talk about their passions, their majors, where they want to go in life. All of them are connected in some way to meditation, spirituality, or medicine. I’m wondering how to make my story sound more exciting than it is. What do I have to bring to this program? Why am I here?

Meanwhile, the days go on. In class, we start learning about Buddhism, starting from the most basic ideas and working our way up. There is samsara, the cycle of birth, life, death, characterized by dukkha, suffering, and the ultimate goal of nirvana, the end of the cycle.

I like these concepts, but I don’t pay attention very well. It’s so hot, and my legs are melting into the velvet cushions, and these ideas are so hard to get my head around. I keep trying to compare it to Judeo-Christianity, life and death, death and resurrection, but it feels so different and hard to grasp. There is a mental wall in my brain, and I can’t cross it.

Eventually, I have to give my introduction to the class. There is nothing overly groundbreaking about it, and others’ stories are much more in depth. Still, the moment I give the introduction, and as I listen to the people who will become my friends share their stories, one by one, it feels like something is loosening inside me. A knot is coming undone, a mental wall begins to crumble.

Maybe there are important things to be learned from this place.

---

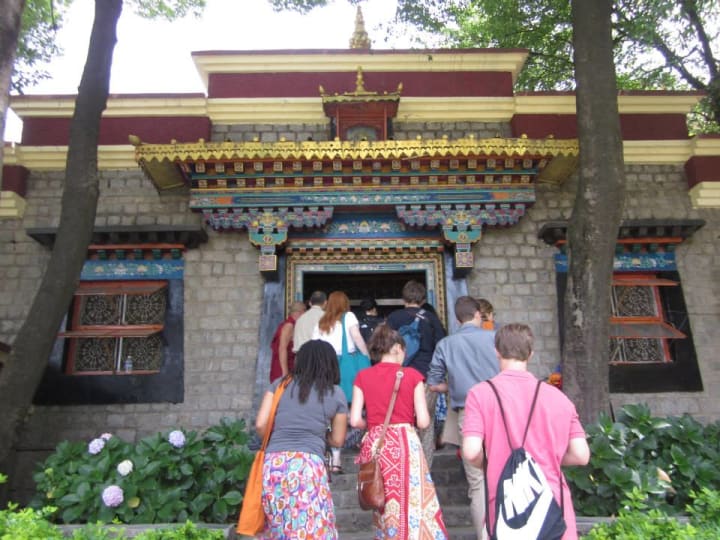

We wake early. There is an excitement about the campus. We are wearing the nicest outfits we have. We load into the fleet of cars and make the winding half-hour trip to the temple complex at McLeod Ganj, the town center of Dharamsala.

At the security checkpoint, our bags are inspected and we are scanned with metal detectors. We are shown into a small room with a series of chairs lined up into rows. In addition to our cohort, there are several professors, as well as a group of monks and nuns. Our study abroad group, though, is shepherded to the front of the room. I’m seated towards the right in the second row. At the front of the venue, there is a platform set up with a chair in front of a large image of the Buddha and two thangka tapestries, flanked by flower arrangements. The room is air conditioned, so it is a comfortable wait.

We wait for a long time. We start chatting. We play games and tell stories. More conversation goes by. We are wondering when anything is going to happen. I start thinking about snacks. Where should we eat after this? I heard there are some great restaurants in town. Maybe I’ll check out that Ashoka place. I could use some chicken tikka masala.

Suddenly, a palpable ripple of excitement travels through the crowd. A hush falls, an anticipatory static. Through one of the side doors, we can see the rustle of maroon and yellow robes, moving slowly closer. Then he enters, and the crowd stands and bows.

Onto the platform walks His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

It’s surreal to see someone so revered and famous sitting ten feet away from us. In person, he radiates the same love, warmth, and joviality that he does in the videos I have seen. His smile is infectious, as is his laugh.

We break out grinning en masse as he begins his talk. He speaks in English, though it is patient and softly accented. The details of the talk are lost to me, but I remember themes of love, universal acceptance, and the fact that at the end of the day, all religions, and those without religion, want the same things. The important thing is compassion. This is a major theme of His Holiness’s writings, and we have been discussing this in class: the overlaps between science and belief, and the threads of contemplation that can run beneath all areas of life.

I like these ideas, and I find myself wishing that the whole world could be here today, listening to this man with such warmth, but who has endured so much, lay out a vision of peace for the world.

After the talk, we go up to the front of the room and gather for a group photo. Several assistants drape white katas over our shoulders, and we arrange ourselves around His Holiness, who stands in the center like a maroon beacon of compassion.

Before this private audience, we were allowed to submit items to be blessed by His Holiness, including prayer cords, katas, or other small objects. Most of us chose to purchase prayer cords at a stand outside the temple complex, and we retrieve them after the talk. Each cord has one knot at the center, which is said to keep the blessing tight in the string.

After the talk we retrieve the items we submitted, freshly blessed. I tie the cord around my wrist, passing it back and forth to fit tight, and I tie the strongest knot I can. It will eventually fall off over a year later, but for a while, there it sits: a multicolor reminder of that short and special time we spent in the close presence of the Dalai Lama.

In the coming weeks, as I reflect on the theme of compassion, I start to see the similarities between the Christianity of my upbringing and the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism. There is suffering, and there is a way out of it. Kindness, humility, and service to others are key. Prayer is another face of meditation. There are major differences, yes, but the root feels the same. India is not like the United States, but it also is. Among this little mountain town in Himachal Pradesh, among the Tibetan community, something starts to feel a little more familiar.

---

It’s colder in the mountains than I thought it would be. I’m glad I brought long pants and a sweatshirt, but I’m wishing I had more layers. Still, while I’m moving, it isn’t so bad.

I’ve entered what appears to be a cloud. I pick my way over rocks carefully, treading in my big brown boots over the rough terrain. The trees have fallen behind as the altitude increases. Now, there are just short shrubs and grasses. Or at least, the last time I could see the landscape, that’s what was there. Now there is just this white mist, the rocks, and the flowers.

My ears are ringing like thousands of little bells. I don’t know where the rest of the group is. I’m slow. This is the longest day hike I have ever been on, but I wanted to prove—to my friends as well as to myself—that I could do it. I’ve been pretty confident all day that I could. That is, until this cloud.

Today is my twentieth birthday. It is a few weeks into the program now, and my anxiety has dissipated. I feel like I am right where I am supposed to be. It surprises me to think back to how upset I was that I wouldn’t be able to talk to my mom today. Somewhere in my brain, I still miss home, and it will be good to be back. But I don’t think about it as much anymore. All that I’m focused on now is this place, India, the mountain: the mist, the irises. The people I’ve come to know, and their stories that they have shared.

Finally, up ahead, I see the silhouettes of my friends. I heave a sigh of relief. I’ve found them, and everything is fine. We keep walking until we reach our destination: the snow line.

It looks less pretty than I was imagining, more dirty and less glacial, but it is still the farthest up a mountain that I have ever hiked. We all take pictures standing among the rocks and the snow, and I pose with my hands in my pockets, orange backpack cinched tightly, proud.

Twenty years old. I am in India and on a mountain, a whole world away from everything I know. Or rather, a whole world away from everything I used to know. Now, I know this place, these people. This snow, and the cows, and the mist, and the country that has, at least for a short time, become a kind of home.

Back at our hostel in the evening, we gather for dinner. Afterwards, Kari surprises me by bringing out a cake. It reads, Happy birthday, Sarahmarie! I am delighted at this unexpected gift. The group sings for me, and I blow out the candles. Someone hands me a beer—my first, ever. A 500-milliliter Kingfisher labeled FOR SALE IN HIMACHAL PRADESH ONLY. I take a sip. It’s kind of weird, but it’s cold, and I drink it all.

Twenty. The start of a new decade. It feels like the start of so many things.

The sun begins to sink behind the mountains, and the sky turns a gentle purple. A few stars come out. They aren’t that different from the stars at home. God is exactly the same here as in Kentucky. Exactly the same with these friends as with my old friends back home. Exactly the same as anywhere.

---

Thank you so much for reading this story! If you enjoyed it, please click the heart button below, or consider leaving me a tip. You can find more travel and adventure stories at my website: sarahmariesb.com

About the Creator

Sarahmarie Specht-Bird

A writer, teacher, traveler, and long-distance hiker in pursuit of a life that blends them all. Read trail dispatches and adventure stories at my website.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.