Irish Faerie Narratives

The Stories of Ireland Imbricated With the Real Parts of Ireland

The Irish Catholic Church is by far, the most powerful institution in both Northern Ireland and Ireland, which are technically separate countries since the schism one hundred years ago. Irish Catholics created communities for themselves the world over. Some of the saints in the Irish Catholic Church have origin stories that are told as part of the Irish fairy story cannon. Catholic Church's hagiography of a saint's life is usually very dissimilar from the folk tale version, but the names and themes are often the same.

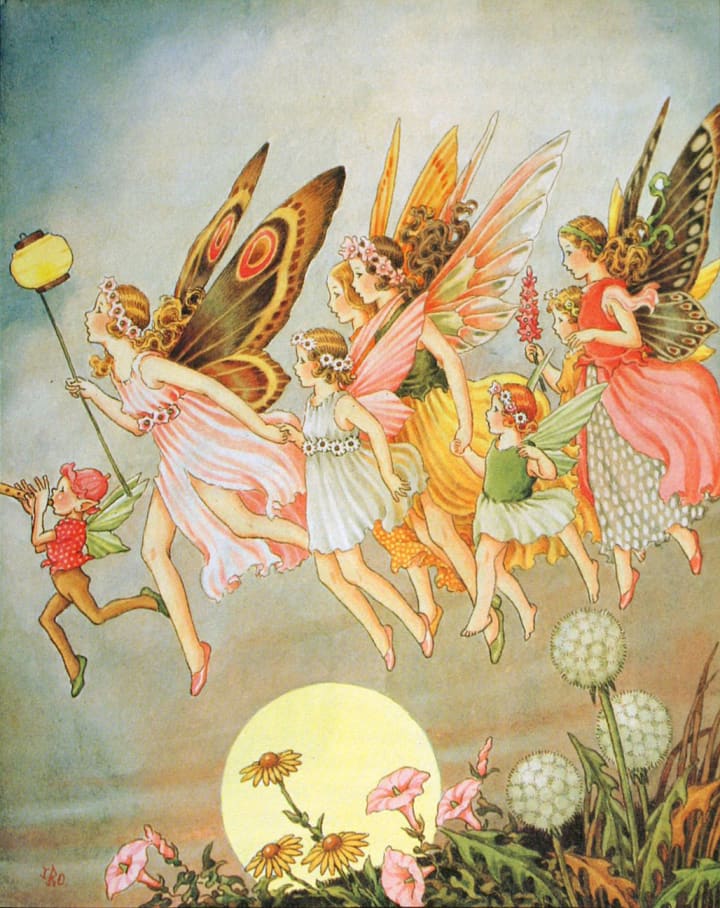

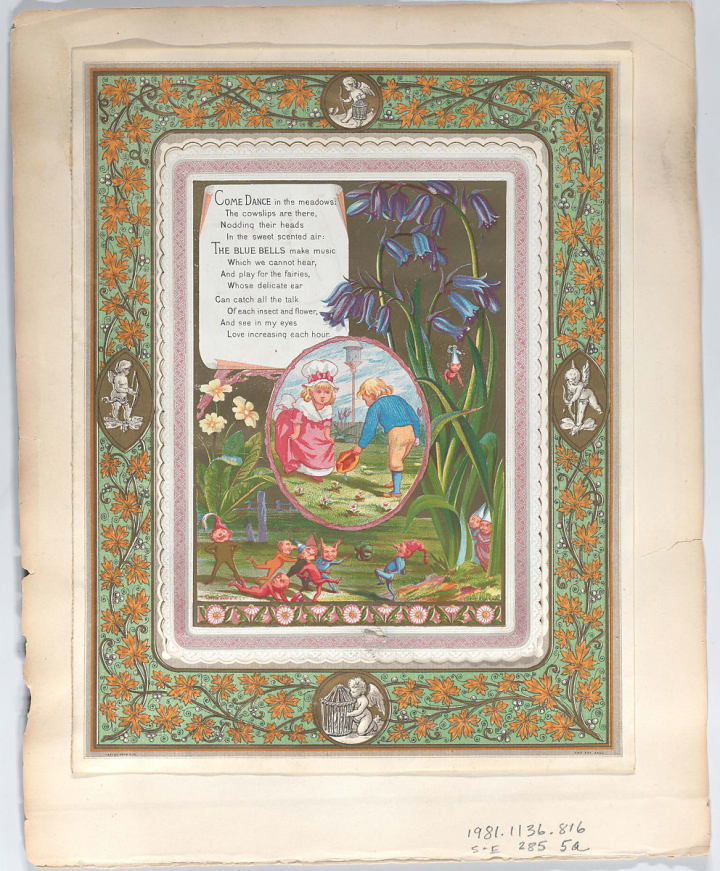

A lot of fairy stories mention the importance of taking the suggestions and warnings of the fairies very seriously, and the consequences that occur if their warnings are ignored. I, personally, am very entertained by just how badly characters are punished in the fairy stories for ignoring the warnings of the fairies. The fairy folk are often described as wearing disguises in order to confuse the Irish people whom they meet, making it unlikely that they are trusted at first. The smarter characters in Irish fairy and folk tales welcome these disguised helpers into their homes or help them along their travels and are rewarded with advice and solutions to jinxes that have been placed on their homesteads.

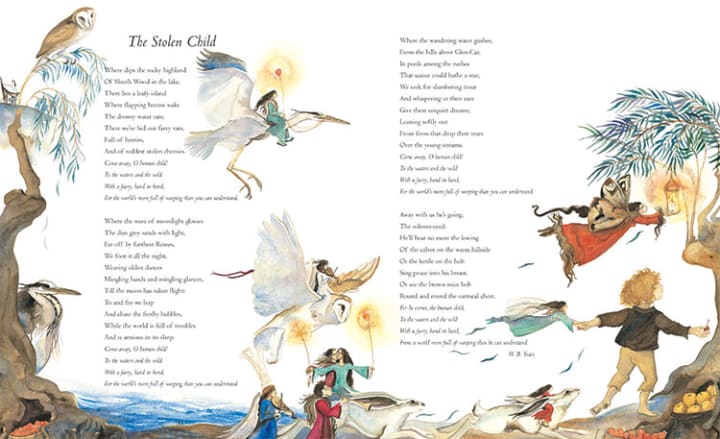

In the book " Irish Fairy & Folk Tales" by William Butler Yeats, " Lady Wilde gives a gloomy tradition that there are two kinds of fairies-one kind of merry and gentle, the other evil, and sacrificing every year a life to Satan, for which purpose they steal mortals" (Yeats 65-66). The process of stealing mortals for the fairies' nefarious purposes are described in more detail a poem of Yeats', which does not appear in this particular book. In " The Barefoot Book of Classic Poems," Yeats' poem " The Stolen Child," describes the traps that are used by the fairies to trap mortals as containing " berries," and "the reddest stolen cherries" (Morris 32). According to the poem, the human children are encouraged to follow the fairies because " [T]he world's more full of weeping than you can understand," (Morris 32). The fairies are trying to convince the human children that the real world, which they naturally inhabit, is full of occurences which cause sadness, which is the origin of the reference to crying. This is not uncommon, for children, or even adults to be misled into trusting happy-seeming, cheerful, yet dangerous strangers who promise them glee and gaeity in a place where there are no real world problems. Real people, in the real world, tend to encounter and deal with complicated situations which cause misery on a daily basis. The humans struggle to avoid the appeal of the fairy's world, consisting of parties where the fairies are" Weaving olden dances, / Mingling hands and mingling glances," (Morris 32). Also, the humans could be attacked by a vicious curiousity about the performance of ridiculous acts like talking to fish: " We seek for slumbering trout, / And whispering in their ears, / Give them unquiet dreams;" (Morris 33). Yeats describes a world which would be appealing to a child on the brink of leaving home to follow the fairies into their fanciful world, contrasting the fairy realm with the dismal and dreary "real world" where sadness exists. I can see how it would be hard for a person to get tricked by the fairies in this poem, however, with my life experience up to my current age, being in my late twenties, I think I sort of know better than to get fooled by the fairy people.

There is a story which I read a children's version of and then read an old-fashioned version of, written using a dialect that one might imagine people might have actually spoken in a younger Ireland. I was surprised to find that I understood perfectly well the jargon in the older version of the fairy tale. I think this is because I already speak and write in a couple of languages apart from English. Guessing the meaning of phrases from context clues is easy if you're trilingual. I have read a lot of Yeats' poetry and luckily, this particular story about bewitched butter is fairly easy to comprehend in its early twentieth-century formulation. The contemporarily published, children's version of this story is a little bit different and I would like to describe how.

In Yeats' version of 'Bewitched Butter,' the principal family is called Hanlon and their family farm is juxtaposed with the nearby family farm, known as Dogherty, which in this version of the story, owns the same number of cows. Both families are known for having good dairy cows. One night, a girl from the Dogherty family comes and asks to milk one of the Hanlons' cows, claiming that she has just come to help the matriarch of the family who is busy with other chores and may not be able to complete the cow-milking that night. Mrs. Hanlon responds to the Dogherty girl, that she is in fact busy, but not too busy to complete her own house-chores. The next night the Dogherty girl returns, with the same demand, and this time, Mrs. Hanlon lets her milk one of her cows. In Yeats' story, after the Dogherty girl has milked the Hanlon cow, it stops giving milk to the Dogherty family. Several days later, the cow's problem was diagnosed by a man they solicited for advice, as having been milked by someone who had cursed it with an evil eye.

This narrative is a bit different from the one written for children, in the Krull book, where the Dogherty family isn't mentioned at all until later on in the story. In the children's story, told by Kathleen Krull, an old, barefoot female witch, wearing a red cloak shows up, out of nowhere, to help the Hanlons' cure their cow, while in the Yeats story, the sorcerer is a male named Mark McCarrion, who lives a nine hour walk away, in a place called Binion. In the children's version of the story, the Hanlon family is described as having a signifigantly greater number of cows than the Doghertys, but the Doghertys' cows had been producing an unnaturally large quantity of milk for a while before the fairy tale took place.

In both stories, the method of finding the party responsible for cursing the cow, suggested by the old witch, as well as the neighbor Mark, consists of boiling nine pins in the milk from the Hanlons' cows. In the children's tale the witch does chanting over the milk as it boils, and in the old-fashioned tale, by Yeats, no chanting occurs. In both tales, the Dogherty girl appears, banging at the front door and begging that the milk and pins be taken off the stove, promising that she will never again curse the Hanlons' cows. In Krull's story, the Hanlons leave for America as soon as possible, because they are so ashamed of the transgression. At the end of Yeats' story, there is no voyage to America described, and instead a couple of other solutions are included, such as heating parts of a plow and putting a hot horse-shoe under the butter churn.

In this story about charmed cows, the fairies are the old witch and the neighbor Mark who help the Hanlon's remove the charms from their cows. The Doghertys are a neighboring family that performed what is modernly known as black magic on the Hanlon's cows. The old fairy lady, disguised as an old barefooted witch, helped the family in the Krull book because they welcomed her into their home. In many stories across all cultures, there is a poor old hag who appears the doorstep with a solution to the family's problem given that she has been received kindly as a welcome guest in their home. In the Yeats story, the Hanlon family specifically sought out the help of Mark McCarrion who lived in Binion. He recognized the curse as having to do with the evil-eye. Mark McCarrion is the fairy character in this story. Both of the fairy characters in these stories are benevolent and knowledgeable about the actions of the antagonistic humans.

" The Leprechaun makes shoes continually, and has grown very rich" (Yeats 125). After reading this, I can't help but wonder, if the Leprechaun has been making shoes continually and has grown very rich, where is the money hidden? Leprechauns are known for being practical jokers (Yeats 125). In the poem, " The Leprecaun; OR, Fairy Shoemaker," by William Allingham, the author sugggests finding a small leprechaun and "holding him tight" and "[Y]ou're a made / Man!" (Yeats 127). I think that the author of this poem was a little misdirected and believes that if a leprecaun is caught, it will tell its captor where it keeps its hidden gold. I think that this is absurd, but makes for an entertaining poem. Since the Leprecauns are catergorized under "trickster," catching one, and demanding to know the location of it gold seems like kind of a stretch. In the stories that I have read, and films that I have seen, leprecauns care far more about keeping their gold hidden than they care about their own lives. This quality is what makes them different from all other creatures of the wood. They literally just like to hide gold. They have a tendency to tinker and continue to work and make things that people or the fairies will buy, so they are actually continuing to provide for themselves, but the point is that they have gold that they don't need and not sharing it is the whole point.

There is no movie where some funny, poor child teaches a leprecaun to feel guilt for being a miser and then everybody agrees that "sharing is caring" and then the leprecaun gives random people free gold. That never happens because it goes against the inherent nature of leprecauns. They know what sharing is, they are just morally against it. It is in their nature to hide valuable items and then not tell anyone where they are hidden.

I entered, once, a branch of the public library system in the city where I live to find one or two of the "Colored Fairy Books" on display for patrons to check out. I have the Lilac Fairy Book at home, which was purchased for seventy-five cents by a member of my extended family at some sort of book sale. Andrew Lang makes the claim, in the Preface: that he "did not write the stories out of [his] own head." (Lang vii). Lang then goes on to describe how ancient the stories are, and Homer based parts of the 'Odyssey' on Irish fairy stories. Personally, I think that this is completely ridiculous, mostly because there were no people living in Ireland when Homer was writing the Odyssey in the seventh century before christ. The "Mesolithic hunter-gatherers" did not even arrive in Ireland until 7900 before Christ. I find it absurd to believe that these stories of farms and towns which were visited, blessed, and cursed by fairy people were composed by the hunter-gatherers who had settled in Ireland just in time for Homer to write the Odyssey. I have no interest in reading the Lilac Fairy book, nor another "Color" of fairy book" because I believe that the author, Andrew Lang is telling a lie, or a serious of them, and frankly, these stories are practically impossible to read. William Butler Yeats was born in 1865 and died in 1939, and his writing is much easier to read. Andrew Lang was born in 1844 and died in 1912 and I cannot understand why anyone would bother to read these unintelligible color-coded bogus fairy story books.

Bibliography of Printed Texts:

Yeats, William Butler. Irish Fairy & Folk Tales. New York, Friedman/Fairfax Publishers/Metrobooks, 2002.

Krull and McPhail, Kathleen and David. A Pot O' Gold: A Treasury of Irish Stories, Poetry, Folklore, and (of Course) Blarney. New York, Disney/Hyperion, 2004.

Lang, Andrew. The Lilac Fairy Book. New York, Dover Publications, INC. 1968.

Morris, Jackie. The Barefoot Book of Classic Poems. Barefoot Books, 2006.

Web References:

Contributors to Wikimedia projects. “Andrew Lang - Wikipedia.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 31 Oct. 2002, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Lang.

“Hagiography - Wikipedia.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 29 Dec. 2002, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagiography.

“History of Ireland - Wikipedia.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 2 Oct. 2001, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Ireland.

“History of Northern Ireland - Wikipedia.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 26 Apr. 2003, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Northern_Ireland.

“Odyssey - Wikipedia.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 11 Nov. 2001, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odyssey.

About the Creator

Sabine Lucile Scott

Hi! I am a twenty-nine year old college student at San Francisco State University majoring in Mathematics for Advanced Studies. I plan to continue onto graduate school in Mathematics once I am finished the plethora of courses which remain.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.