I am the daughter you didn’t know you had. My mother, the woman you once called Wife, had me fourteen weeks after your divorce was finalized. You didn’t know she was pregnant because she did not tell you. The divorce was as simple as it was painful, made under the safety blanket of a one-year protection order. There was no in-person mediation, no court appearances. She paid for a good attorney who blocked you from her, and me. I was melon-sized in her round belly when the attorney mailed Mom the final papers, which you reluctantly signed and notarized. You asked to see her one more time. The attorney said no.

For a long time, Mom hated you. She was glad to be free of the drugs and the sounds you made when you weren’t sleeping and the barrage of emotional insults, which later became physical. You don’t need me to remind you of the marks you left on her body. But you left with a wound that lingered, a gaping hole that your ex-wife had to slowly dig her way out of.

The attorney told her that it wouldn’t be worth the legal fight, that she should just let the money go to you so that the divorce could finish. Think of it as the price of freedom, the attorney offered. She was a woman twice Mom’s age then. She wore sweater vests and kept a small garden in her nice old house on the nicest street in town. She could not understand why my mother fretted over twenty thousand dollars so much—half of the retirement money she’d acquired after teaching at the university for nearly a decade. State law said that legally, half of her retirement was yours. No matter that you had no assets to offer her. After nearly a decade of trying and failing to earn a doctorate, your addictions butting in like a rude passenger, all you could give my mother was your complete absence. The attorney helped Mom transfer that money over to you, money you did not earn, and you left the country while she prepared to have me. We never heard from you again until you were already dead.

We didn’t have an easy life, but we made the best of it. Mom quit teaching at the university after I arrived, but she kept us housed and fed with small jobs—tutoring, tailoring clothes, the mundane sorting of others’ mail. When I got old enough, she took another job teaching refugees at a local community college. She liked this job best and stayed for twenty years. The women from war-torn places always smiled in class and did their best learning English, one word at a time. This filled her with something like hope. I thought we had it rough, but look at what these women have been through, she would say. If they can find something better, so can we, Emi.

She did not talk of you much, other than when she was tired or anxious. I wonder what exotic adventures your father is having in Asia she’d quip, usually while hunched over her sewing machine. This was the place she always assumed you’d be, since you often spoke of it while you were married. You promised Mom you would take her to see The Great Wall someday. She never forgot that.

When your package arrived in the mail, Mom was already in her second month of chemo. We don’t know how you found our address. When she saw your name written in your thin cursive, she threw the manilla envelope on the floor as if it might be a bomb. Don’t open that, she said to me. Suddenly tired, as she so often was then, she shuffled to the couch. As I spread the quilt she’d made for me across her thin body, she softened. Open it if you want, but don’t tell me what’s inside. I want to die in peace.

It took me nine days to work up the courage to tear that small package open. I was afraid of what I would find, but my curiosity was stronger. Mom told me I get my curious nature from you.

This is what you left us: three different debit cards from Chinese banks and a slim black notebook. Inside the notebook, written on the front page, was instructions for the cards. It was the first time I ever saw your handwriting in a complete sentence. Use this PIN for all three, you wrote. And under a strand of six numbers, there was this: Forgive me. A weak command. I looked more closely at the numbers and realized they were the month and year of your divorce. Without telling Mom, I took the cards to an ATM that accepted foreign Visa cards. The total amount came to twenty thousand dollars.

I did not read beyond the first page of your notebook until a few years later. There were more pressing things. I slowly withdrew all the money. It took me a month. Every time I walked up to the ATM, I peered nervously over my shoulder, as if a Chinese government official might appear out of thin air and tell me to stop. This did not happen. I used the money to pay for the rest of Mom’s cancer treatments and later, her funeral. Her attorney from all those years ago was right. Twenty thousand dollars is not as much as you’d think when you have cancer. It eats money as fast as it eats the body.

I ordered dozens of sunflowers for her wake—her favorite. One of the few details I know from your wedding is that you had sunflowers. I think you would have approved.

Mom hated that you got to take some of her money and travel the world with it. She kept that retirement account with the university, which grew into significantly more dollars over time. She vowed she would take me to see The Great Wall with those dollars, and then…cancer. We like to think we have choices, but there are always fewer than we want or need.

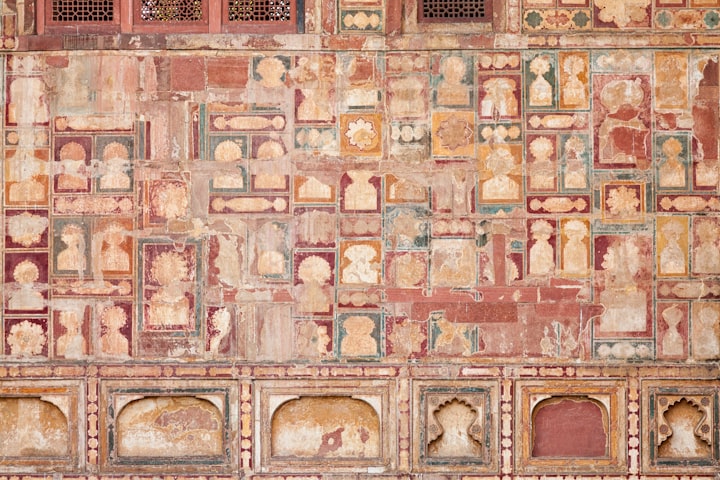

I was disappointed with what I read in your little black notebook. I wanted confessions of guilt, of daily torment for leaving a family behind, but instead I read detailed records of where you went and what you saw while you were there. You spent most of your time in China, but you traveled to other places, too. In Bangkok, you wrote: Beautiful view from the river and When you walk through the largest temples, the coins people drop into the donation bowls sound like rain. In a little town in Cambodia called Kep, you were fascinated with the large Coca Cola bottles they repurposed for gasoline in small roadside stands: The gold liquid sparkles in the sun. Almost looks drinkable! You mentioned Hemingway more than once. It seemed like you were trying to be a man that you were not. I don’t think your writing would be particularly interesting to anyone but me.

The writing from your small holiday trips was flowery and impersonal, but when I read entries from your days in Beijing, I felt like I knew you a little more. Everything is gray today, you wrote once. Why do I stay here? That question was a window into your vulnerability. You did not mention the family you were forced to leave, and you didn’t reveal how you managed to keep yourself stable enough to hold a job, either. After all the years you spent trying to finish a Ph.d., you ended up being an English teacher in China. I’m glad Mom didn’t know about this. It would have really pissed her off.

You only mentioned a detail of your past once. When you saw The Great Wall for the first time, you wrote, Emily would have loved this. I stopped breathing for a moment. How did you know my name? But, of course: Mom named me after her, shortening three syllables into two. It was probably her way of showing just how little she needed you.

I’m sure you thought you were doing something important when you left those cards and that notebook for Mom. Repaying her the twenty grand and leaving behind small, mundane details of your life abroad was probably your way of saying, This is what I did after you forced me out. I tried to build a life without you. It was just okay. Because that’s what I felt, more than anything, when I read your words: that you were just okay. You saw a lot of beautiful, fascinating stuff, but without anyone to share it with, what was the point?

I found out you died about a year before Mom did, in a hospital bed in Bangkok. You were alone. You hadn't seen your real home in over twenty-five years. I tried to imagine what your last thoughts might be, and whether the painkillers the nurses gave you in that Thai hospital reminded you of the days you took whatever you could to hide your pain and keep it from exploding out of your fists. I wondered if it was at all possible you knew about me, on some psychic level.

I’ve had a daughter of my own since you both passed. I have given her a name, but I don’t want you to know it. Not yet. One day, when she’s old enough, we’ll travel to Asia together. We go to the same spot of The Great Wall where you stood, and we’ll sit on a little boat in a river in Bangkok, just like you did. The strange bottles of gasoline might still be there in Cambodia when we arrive. We will see everything you saw, but I will not tell her about you unless she asks. We will not take this trip for you, but for Mom. And we will buy our own notebooks and fill them with our own thoughts, because this daily practice was the best thing you left behind. Maybe one day, after I fill one of my own, I will be a little closer to knowing who you were.

<END>

About the Creator

Jenny Rowe

Jenny Rowe lives in Iowa City and teaches ESL to students both here and abroad (remotely). She was teaching English in Beijing before the global pandemic. Her work has appeared both locally and overseas in Beijing's Spittoon Collective.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.