Culture Shock on a Small Scale

How I grew to love both my tiny apartment and new life in Japan

Rather than a culture of uncaring apathy, Japan is a culture of unobtrusive care. —Angela Volkov

‘Well, this is dismal,’ I thought, sitting on the edge of my narrow new bed, ‘six months in here’. It certainly felt like a prison sentence; at fifteen square metres, the apartment was only slightly larger than a holding cell at the Old Melbourne Gaol (that's 'jail' to you Yanks).

My new Kyoto apartment was a thirty-minute bike ride to Doshisha University, unlike my first choice of accommodation, a girls’ dormitory a leisurely ten-minute stroll away. Another spot of bad luck: I was on the third floor, and power to the lift had been cut off by management due to the unspecified hijinks of the prior year’s students. (Doing laundry required schlepping up four flights of stairs with a laundry basket. Just kidding, what cash-strapped college student buys a basket? It was a bin bag, and you know it.)

Speaking of Doshisha University, its founder, Niijima Jou, was a stowaway to America, eager to study Western science and learn about Christianity during Japan's isolation period when almost no one was permitted abroad. (Guess Japan had a hard time dealing with its culture shock; their isolation period lasted over two hundred years) Had Niijima been apprehended, he would have certainly been executed. As it stands, after graduating from Amherst College in Boston, he returned and opened an English school in Kyoto, which later became Doshisha University, and was honoured as an educator.

By the way, Niijima's moustache manages to be even more epic in real life than in the manga (comic book) — no mean feat:

My home for the next six months was furnished with a bed set against the wall, a desk opposite, and a squat particle-board bookcase wedged in along the edge of the desk, to the right of the frosted-glass window (a common privacy feature in Japanese homes). The window had no fly-screen, something I discovered just before the underwear I had been drying on the ledge was about to flutter outside. (I don' have any photos, alas, it was several now-defunct phones ago.)

Within moments of unlocking the door, with the student volunteer still in the room, I began to unpack my suitcase and arrange my new living quarters to my liking. She told me, 'Yukkurishite kudasai' ('Take it easy!') as I worked like a woman possessed. I pulled out a box of macadamia chocolates with a picture of a koala munching eucalyptus on it and pressed it into her arms to distract her. On our second and last trip together to the municipal office to have me registered as an 'alien’, I gave her a dodecagonal 50 cent piece with which she was similarly chuffed.

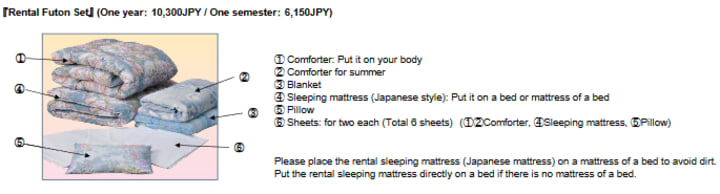

My first order of business was the bedding: a futon to go over the doubtless despoiled mattress, as well as sheets, covers and a small, square pillow filled with the traditional buckwheat grain. This pillow would become the bane of my existence; lumpy doesn't begin to cover it. (However, as even cotton-stuffed pillows in Japan are unusually firm, I never bothered to replace it.) Here's the set in all its glory:

I’d bought my friends souvenirs from trendy Shinjuku while on a pre-semester holiday and now these served to gussy up the place. I stuck a ‘jidou doa’ (‘automatic door’) sign from Kappabashi — the restaurant supplies district of Tokyo which sells hyper-realistic food replicas— outside, to add a final ironic, kitschy touch to my new abode. (I like to think it added a modicum of confusion to every subsequent tenant’s and visitor's introduction to the apartment.)

I’ve described the main room, however, there was also a genkan: an entranceway with room to stash your shoes (as in many cultures including my own, wearing shoes indoors is verboten) which lead into the raised kitchenette and bathroom. Both were tiny. There was no bench space whatsoever in the kitchenette, and the toilet was set at an angle so as to fit the bathroom.

Despite the bathroom’s compactness, there was a bathtub; Japan is a bathing-obsessed culture. It was temperature controlled (I kept the water at a very toasty 42°C/108°F degrees), and deep enough so that only the tops of my shoulders were above the water when filled to maximum capacity. However, I did have to sit with my arms wrapped around my knees; the tub was deep but not long, just like a traditional Japanese cedar soaking tub.

Here's a video tour of my apartment I found online. In my day we weren’t provided with an in-room fridge and microwave (luxury!). But this is pretty much what mine looked like:

Although the view out of my window was of the bicycle parking, the apartment block faced a temple; occasionally I was roused from sleep by the chanting of monks from Nishi Hongan-ji. A stately, black behemoth, it somehow manages to remain austere despite all of its gilding and intricate detail. It leaves you awed and cowed in equal measure as it swallows you up into its cool, fragrant darkness.

It is beautiful.

Other things to wake me up on weekend mornings included a campaign van blasting political slogans in a shrill, cheery voice and an earthquake that shook the window pane. By now accustomed to earthquakes, I decided this was about a 5 on the Richter scale, and rather than crawl under my desk like you're supposed to, I fell back onto my lumpy buckwheat pillow and promptly fell asleep. (Speaking of freaky weather, I once got the day off because there was a typhoon warning.)

Culture shock on a larger scale

The months I spent as a foreign exchange student in Kyoto were some of the best of my life: living out of home for the first time, adapting to a foreign country, not to mention something I sorely miss these days: weekdays consisting of a few hours of intense intellectual stimulation followed by swathes of free time to reflect on and enjoy life. (In the past few months I've decided to work only part-time to focus on my writing; on those days off I'm living the dream. I've only just realised this, and that I've been taking it for granted. Ironic.)

In that short space of time, the six months I lived in Japan, so much happened that I can only seem to approach the subject of Japan through narrow lenses — my signature seal, my fear of accidentally ingesting horse sashimi, my tiny student apartment.

Describing the slow process of assimilation isn’t an easy undertaking. When I arrived back home, my parents asked me what had surprised me the most and I lamely replied that Japan was more humid than I had expected. What else could I say and be understood? My preconceived notions would naturally differ from that of a person who hadn’t been fascinated by Japan from a young age — how could they possibly relate? There were no big surprises, only difficult to articulate nuances. I was prepared and yet nothing can prepare you, truly, for submersion in an entirely different culture.

The curious case of the woman on the road

Let me illustrate with a story. On my first night in Osaka, Japan, I met up with a friend, a fellow foreign exchange student already living in Kyoto. She found a wrinkled Yu-Gi-Oh! card on the train carriage floor and handed it to the conductor, who took it with both white-gloved hands as it were a gift or a business card and thanked her profusely, bowing over and over. What a waste of time, I thought.

That same night my friend and I walked past a uniformed woman passed out in an alley. Her body on the footpath and her legs over the curb. Considering she was partially on the road, I worried someone would run her over; I worried she had passed out and needed medical attention. My friend managed to talk me down from checking on her ('We shouldn’t disturb her') or calling an ambulance. I thought my friend callous. Sociopathic, even. In actual fact, she was assimilated, and this contrast — the silly detour to hand in a children’s playing card versus what I perceived as apathy toward a fellow human being — was my first bit of culture shock.

After living in Japan a little longer, I came to realise the woman was perfectly fine where she was, lying half on the road. She was likely taking a nap before a night shift, and drivers would have carefully manoeuvred around her. Rather than a culture of uncaring apathy, Japan is a culture of unobtrusive care. (And a culture where sleeping in odd places is considered socially acceptable.)

Similarly, if you fall off your bicycle in Japan, no one will come to your aid or inquire 'Are you alright?' unless you are grievously injured. Rather, they'll avert their eyes as they walk around you. This is done to preserve your dignity; allowing others to save face is something the Japanese consider to be of the utmost importance.

Remember all that negativity at the start of my story? All symptoms of grappling with an unfamiliar environment and customs. Two months into my exchange program and I felt completely differently about my apartment, and about Japan. Tiny apartment — perfect, less of it to clean and heat. Broken elevator — incidental exercise. Far away? More time on my bike enjoying the scenery along the banks of the Kamo River (pictured below). I guess it's just a matter of perspective.

Tips for fish out of water

When you're a fish out of water expect to flounder (or is that just codology?). It doesn't matter whether you've gone to live overseas, started a new job or college, or suddenly found yourself single. It'll take a while to find your sea legs (yes, I've been naughty after I promised you no more nautical puns.)

The thing about living in a foreign country is that it's not at all like being a tourist. A tourist's life is sublime, mostly carefree sightseeing and gluttonous food gorging. A resident's life is paying rent at the post office (well, at least in Japan it is), opening a bank account, finding a good phone plan, and figuring out what is and isn't recyclable.

Rather than being cossetted in the unreality of various liminal spaces like airports, train stations, and hotel lobbies, all staffed with people used to dealing with befuddled tourists, you deal with regular people. They'll have to tap you on the shoulder to teach you to queue in a very particular way for the ATM or inform you that the bank is closed on a Wednesday and, inexplicably, its ATM along with it. (Oh, Japan, you're such a cash loving culture but you don't exactly make it easy.) And while every country will have its jerks, mostly your early days will be a series of misunderstandings rather than bona fide misfortunes.

Just so you know how discombobulated I felt, check out my email home after just one week in Kyoto written September 2009. The strange punctuation is a product of being confounded by Japanese keyboards; the immaturity a product of being barely out of my teen years; and the cause of my frustrations are enumerated below:

Kyoto people are lovely, of course. I suspect the misunderstanding above was a product of Japanese incorporating many English loan words that have a different nuance than in the original. Another misunderstanding resulting in becoming crestfallen when a convenience store clerk told me 'wakarimasen' (I don't understand) when I asked her for directions in accurate and well-enunciated Japanese. In Japanese, 'wakarimasen' is often used in place of 'I don't know' ('shirimasen') when you really ought to know (for example, when someone asks your spouse's phone number and you've plum forgot).

The clerk wasn't being dismissive or disparaging my attempts to communicate, she simply didn't know how to get to a famous and nearby castle in the neighbourhood where she worked. So you see, there's a difference between knowing (Someone was rude to me because I'm a foreigner) and understanding (It was an understandable misunderstanding). A fabulous life lesson courtesy of the Japanese language.

Incidentally, that's precisely why culture shock takes so long to shake off. Familiarity is not the product of a single encounter, nor is it a matter of semantic knowledge. Knowing the language and customs of a foreign culture is not quite the same thing as understanding or appreciating them. That takes time and patience. There's no way to rush the process; the process is just life. One day you'll be struck by it all: the new friends, routines, favourite hangouts and foods, the prettily decorated and superbly located apartment, the beloved second-hand squeaky bicycle, and you'll wonder why you ever felt lost, firmly anchored as you are.

One day, you'll exchange a look of conspiratorial chagrin with a local woman scribbling addresses on her New Years cards because, just like you, she's left them to the last minute and the post office (which you've finally located) is about to close for the day. Once annoyed by Japanese middle-man culture, you'll sit at an izakaya and over drinks thank your mediators for helping you smooth over a dispute with your university back home.

You'll ride your bike down the narrowest of spaces, between the railing blocking you off from traffic and the moat of the Old Imperial Palace, lifting your umbrella high to make room for another cyclist to pass. (A skill even more essential than killing it at karaoke, which you will do every Friday.)

The feather on your cap is when an out-of-towner, a Japanese person, stops to ask you (you!) how to get to Kyoto Station ('wakarimasen!'). And, once you've finally assimilated, it's time to fly home to face an even greater challenge: reverse culture shock (coupled with newfound sympathy for visitors to your home country). But, well, that's a different kettle of fish, and therefore a story for another time.

About the Creator

Angela Volkov

Humour, pop psych, poetry, short stories, and pontificating on everything and anything

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.