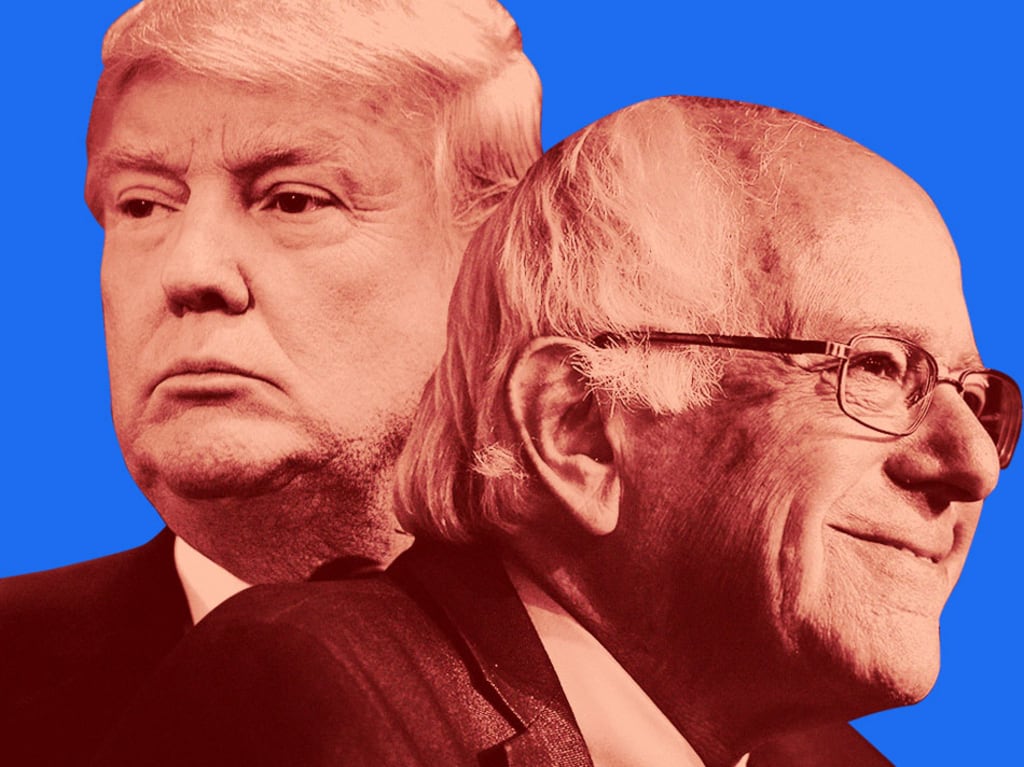

Donald Trump And Bernie Sanders Are Cut From the Same Cloth (an Essay)

Looking back at history and taking a critical approach to contemporary political phenomena is scary.

Traditions of thought, such as liberalism and realism, have recently evolved into not quite as easily definable concepts as they relate to modern political thought movements. Aspects of the modern political movements as seen today seem to lend themselves to a more totalitarian quality than in the past. First, the protesting of the Dakota Access Pipeline and the fact that social media, a technology and thus a liberalizing tool, is not used to flatten the world is a small example of how the dominant tradition of thought today is not so easily definable. But, more crucially, modern political movements, such as the Bernie movement and the Trump movement, as they pertain to the destabilization of the traditions of thought, prove that there is a contemporary appetite for totalitarianism.

It is not the case that conservatism is on the rise and therefore that might be the cause of totalitarianism emerging, nor is it the case that liberalism and globalization is emerging as a neoliberal capitalistic mechanism that is forcing totalitarianism upon a nation from the top down, nor is it the case that hyper liberalism is causing a rise in totalitarianistic ways of thinking amongst the population. Instead, the case is that a distinct way of interpreting the traditions of thought have become a trend in the global political landscape which influences people to express their beliefs in totalitarianistic ways no matter where the movement lands on the political spectrum.

The Dakota Access Pipeline Protests and What It Means

So, in order to understand how the decentralization of the classical liberal ideology is happening, it is crucial to understand what specifically liberalism means and how it applies to current political movements such as the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. Different theorists have different interpretations of what the term means and what it applies to. John Mershimer, in his text called The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, explains liberalism through a comparison to its critiques from realist scholars. Liberalism, in summary, is an “optimistic” (Mershimer, 13) theory of international politics including the idea that good states are cooperative with each other and achieve mutual benefit through international trade of goods and of ideology. Fukuyama takes this a step further and suggests that technology plays a role in the cooperation which eventually leads to a culturally flat world. But, as these theories are often used to describe the modern political landscape, new phenomena has occurred that destabilize them.

The protesting of the Dakota Access Pipeline has been a controversial topic covered by the media for almost a full year and has been steadily growing in popularity and popping up more and more on Facebook and Twitter newsfeeds. This, when put into context of Francis Fukuyama’s theory of a “Technocracy” as mentioned in his piece titled The End of History?, means that technology isn’t solely flattening the world culturally in the sense that Fukuyama meant it. The fact that social media in particular has made cultural awareness more accessible to the masses and has spurred a nationwide outrage at the disregard for the wellbeing of an ethnic group means that classical liberalism, as it pertains to economic prosperity as well as homogeneity, is not fully aided by the advancement of technology. Society is not emerging into a liberal society (or a neo-liberal society) where, as Fukuyama states, advancements in technology further the liquidity of markets and economic prosperity. However, the definition of a flat world the way Fukuyama describes (the homogenization of the world and the creation of a global community) is not the only way a flat world can be interpreted. The flattening of the world can also be flattened by tolerance of other cultures and a global understanding of each other's differences. This question of how to define the flattening of the world as it pertains to liberalism raises more questions as to what tradition of thought global society is in today. Since the world is currently in an economically liberal state but the world is evidently not progressing in the specific liberal direction, Fukuyama argues, then what tradition of thought is society in or progressing towards now?

Liberalism

When thinking about liberalism historically, it is evident that the narrative in the United States, at least since the industrial revolution, has consistently been liberal in the sense that Republicans and Democrats both believe in an a strong middle class and the prosperity of the individuals that make up the nation and want capitalism to function in a productive role to the nation. Essentially, both parties believe in the “American dream.” It’s just that Republicans and Democrats have different views of how to go about achieving that goal. But, the cohesion between these two liberal viewpoints, as explained by recent political phenomena, is being torn in the sense that fascist support is rising from the right with the election of Donald Trump, while socialist tendencies are considered from the left as seen in the youth’s hunger for a new societal system and a contempt for the financial system as a whole and as expressed in the huge support for Bernie Sanders. It is also important to note that there are, as of late, socially responsible financial practices that have emerged that connect social liberalization with capital liberalization and is thus beginning to qualify a previously, and exclusively, quantitative practice. So, the fact that there is contempt from the alt-left for the financial system as a whole as well as new progress in the effort to make liberalization work more effectively as initiated from the political left, just shows that liberalization is becoming more fractured in the context of the nation’s identity. And, if disregarding the effectiveness of capital to create a happy and functioning nation isn’t enough to suggest totalitarian tendencies are emerging in the political landscape, the fracturing of liberalism itself signals the destabilization of a national identity which could lead to mainstream totalitarian thought.

Realism

Realism, on the other hand, is characterized by militaristic defensiveness and the idea that the furthering of a nation's prosperity is dependent on its dominance over other nations as opposed to its cooperation and mutual benefit with other nations. As seen in the Alt-Right movement, starting with the formation of the Tea-Party (maybe in a backlash against the populist campaign Obama ran and won with) to the Freedom Caucus and finally to Donald Trump’s election, realism is emerging in a typically classic liberal society. So, what this means is that there is an un-cohesive national identity, one that is divided along the lines of, in the US for example, not only different interpretations of furthering liberalization (Republican or Democrat, liberal or conservative, etc.) but divided at the point where liberalism as a whole is questioned (and fascism, communism, and/or socialism gains support against the current system) no matter what side of the political spectrum the questioning comes from. This factorization and destabilization of ideological pillars of thought is one of many strong precursors to a totalitarian takeover.

The Political Environment of Trump and Bernie

To understand how specifically this warping of traditions of thought relates to an emergence of totalitarian thought it is crucial to examine the 2016 presidential election and the two populist movements that gained tremendous momentum. From the politically democratic side, Bernie Sanders saw his “grass roots” movement flourish with the aid of social media and the young generation’s appetite for social justice, repercussions for the non-marginalized social groups in America, and the financiers of America that have contributed to inequality. Some aspects that legitimize this as a liberal movement is that its focus is on the liberalization of social capital in the sense that in doing so, social equity will be achieved and in turn will, without conflict, make people live better and will improve the lives of the nation's citizens.

However, much of this movement became aestheticized. What that means is that there are certain archetypes that, to certain subscribers of this movement, trigger opinions of a person or group of people in a profiling manner that enacts prejudices against these people (who to them are no different than the archetypes or ideology they represent) and are thus labeled evil. While the certain social groups that are prioritized are picked out not by actions or merit but by identity politics in a way where the most marginalized and most oppressed has more claim to legitimacy in what they demand or advocate for. This is crucial because willingness to ignore merit and give priority to ideas that come from certain identities rather than from merit itself is characteristically totalitarian. Arendt points out, when talking about Hitler's rise to power in Nazi Germany, that, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, true and false, no longer exists.” (Arendt, 474). Moreover, many of the movement’s defining aspects is that reparations for social injustice entitle certain social groups to have a voice while others should not have one and should not be listened too. This type of prioritization of specific groups of people and demonization of people within the nation is a key aspect of the rise of totalitarian thought within a political movement.

From observation, particularly people who work in finance endure a large dose of ostracization from this movement which is uncharacteristic of liberalism. Unfortunately, there is a case to be made that religion, specifically Judaism, has been tied to the cruel aestheticization of the financier what with the stereotypical history of the Jewish banker. With the pro-Palestinian movement on the left, coupled with the alt-left’s hatred for the financial system, it is imperative that the resurgence of anti-semitism, as is pertains to Jewish stereotypes as bankers, as well as a perceived tie between support for the state of Israel and being part of the Jewish community, not be left out of the conversation when talking about the current political climate and its relationship to totalitarianism. Unfortunately familiar, the Jewish community as of late has not entirely found refuge in politically Democratic alignment due to the emergence of the pro-Palestinian movement and some people’s ignorance and bias as to how Jewish people don’t necessarily have to identify with the state of Israel (specifically Benjamin Netanyahu). Also, anger against the stereotypical Wall Street banker after the financial crisis and during the “Occupy” movement. Yet, the Jewish community isn’t completely accepted into the conservative right’s political agenda because it’s predominantly Christian and supports the existence of the state of Israel but doesn’t explicitly support the Jews themselves. The interesting aspect of this though is that in the age of aestheticized ideology and a thirst for simplification, identity politics is used as a simplifying tool, especially in this case, to make sense of the world. So, it makes sense that the aesthetic and anti-semitic image of a Wall Street banker was adopted and is so crucial to the alt-left narrative’s unifying enemy.

It is interesting that moneyed capital plays no role in the alt-left’s view of liberalization. Typically, the access to capital and openness of borders to both social groups and nations is a defining aspect of liberalization and there is a continuity between liberalization of social groups, culture, access to information, and capital. But in this movement, capital is exclusively left out as seen in Bernie's proposed protective trade policies. The liberal movement has turned from the prioritization of a nation as a whole and to the progress of increasing welfare for everyone in the nation into a movement that prioritizes small social groups over the nation as a whole.

What ties this all together, and as Fredrik DeBoer and Conor Friedersdorf articulate in an article titled “Why Can’t the Left Win?” published in the magazine The Atlantic, “The problem with making your political program the assembly of a moral aristocracy is that hierarchy always requires exclusivity. A fundamental, structural impediment to liberal political victory is that their preferred kind of moral engagement necessarily limits the number of adherents they can win. It’s just math: You can’t grow a mass party when the daily operation of your movement involves finding more and more heretics to ostracize from the community” (Friedersdorf). A key point the left needs to remind themselves of, as as Arendt points out multiple times in her writings on totalitarianism, is that liberal movements are not exempt from totalitarianism. Communism, Socialism, and Fascism all use “exactly the same” (Arendt, 265) tactics to inspire and capture supporters.

The Trump movement, as characterized as a modern conservative movement, has classic connections to the rise of totalitarianism and many criticizers of the movement have called it Fascist. The best way to the “temporary alliance between the mob and the elite” (Arendt, 326) is a key characteristic in the rise to a totalitarian regime that is blatantly evident in Trump’s rise to power. Trump embodies the entitled and elitist Republican yet his movement brought in and was built to include the undereducated white working class voter and an ideological alliance was encouraged between the wealthy elite and the “mob.” This fact alone is what many credit Trump’s election to. Another key aspect of Trump’s movement is his contempt for facts and his voters unwillingness to believe facts. This is what, as Trump himself calls it, “fake news.” Arendt points out that, “Before mass leaders seize the power to fit reality to their lies, their propaganda is marked by its extreme contempt for facts as such, for in their opinion fact depends entirely on the power of man who can fabricate it” (Arendt, 350). Moreover, the alliance is based upon the establishment of a common enemy: immigrants and the system (similar to the Bernie movement where the common enemy was the campaign finance system and the financial system and the people who run them). Arendt’s statement on the psychological manipulation of the masses nails, spot on, what the Trump team did consistently to maintain legitimacy amongst its supporters:

“The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.”(Arendt, 382)

Another striking aspect of both the Bernie and Trump movements is that the ideology in these movements are heavily personified. Even when Bernie Sanders came out in support for Hillary Clinton’s platform, hundreds of Bernie supporters showed up to picket the DNC by chanting “No TPP,” a demand that, historically, would be deemed conservative as it calls for the de-liberalization of trade. And, the Trump supporters, no matter what he says or does or lies about or contradicts himself about, always stick by him because, identically to those Bernie supporters, they rationalize that giving up on the person they support is giving up on their own ideology. As Arendt points out, the personification of ideology is a crucial symptom of totalitarianism.

“In substance, the totalitarian leader is nothing more nor less than the functionary of the masses he leads; he is not a power-hungry individual imposing a tyrannical and arbitrary will upon his subjects. Being a mere functionary, he can be replaced at any time, and he depends just as much on the “will” of the masses he embodies as the masses depend on him. Without him they would lack external representation and remain an amorphous horde; without the masses, the leader is a nonentity. Hitler, who was fully aware of this interdependence, expressed it once in a speech addressed to the SA: ‘All that you are, you are through me; all that I am, I am through you alone.’”(Arendt, 325)

It is thus evident that, to some extent, the particular way in which modern liberalism and modern conservatism, as it pertains to realism, have been decentralized suggests that totalitarian thought is emerging. From the “Bernie or bust” people picketing the DNC, to thousands of Trump supporters maliciously chanting “build the wall,” totalitarian ways of thought, subtle or blatant, can be found emerging in the modern political landscape. The scariest aspect of the modern political climate is that one of these movements was successful in a political campaign to be the President of the United States. Hateful rhetoric managed to resonate with at least half of the country while the voice of reason and merit seemed to drown out in a stormy mess of slander that was the 2016 presidential campaign season.

However, hope can be found in the fact that the Obama campaign, back in 2008, ran on the idea of change and reform and won by turning out previously disenfranchised voters to the polls. If it were 2008, it would be plausible, based on the studied precursors to totalitarian uprisings, that there are a few (significantly less, but still a few) similarities between the Obama campaign and a totalitarian movement. But, as his two terms are complete, it is evident that, throughout his time in office he has embodied all that is classically liberal about the priorities of the United States. Maybe, it is possible that tapping into populism and maybe even getting into totalitarian territory to win votes is a tried and true method of campaigning and maybe the 2016 presidential election is no different, just in the sense that the new president of the US has a steeper than normal learning curve.

However, it is never safe to assume all is well when there are clear and many warning signs of totalitarianism emerging within one of the most powerful nations in the world. Warning signs do not just have to come from theory. It can be seen just be observing the immediate world. Even from observing how student government elections are won, it is evident that the new voting generation votes heavily based on identity politics. According to a VSA member, the people who mentioned their identity, particularly as a part of a minority group, consistently won elections despite how comprehensive their mission statement was. Although correlation does not imply causation, it is important to consider the implications of this voting rationale. Even though it may seem fair and that reparations are just (and that student government elections work very differently logistically and are significantly less important than national elections), the process itself, when examined unbiasedly, could be a dangerous sign in the sense that the new voting generation, because of ideological simplification coupled with misdirected dissatisfaction in the nation, is more likely to let identity, whether racial, cultural, ethnic, or even ideological, influence their world view. The implication of this could, in the worst case scenario, lead to support for totalitarianism.

Works Cited

Mearsheimer, John. “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics”, University of Chicago, 2003.

Fukuyama, Francis. The National Interest, “The End of History?”, 1989.

Arendt, Hannah. “Origins of Totalitarianism”, Harcourt Press, 1966

deBoer, Frederick. “Where Online Social Liberalism Lost the Script”, 2014 http://dish.andrewsullivan.com/2014/08/21/where-online-social-liberalism-lost-the-script/

About the Creator

Graeme Mills

I am an entrepreneurial minded person who has developed unique skills in the stock market. I have also been an artist and musician my whole life and desire to live independently off my skills.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.