Yes, of course race is a social construct

Does race exist? Yes and no. It's more complicated than we think.

While I was in college, one of my affable hippie professors declared, to an audience of Poli-Sci 101 students, that race was a "social construct." Observing the confused looks on his students’ faces, he elaborated. Race is a man-made concept, he said, and is not necessarily based in science. Instead, racial labels (including "black" and "white") change with the times--and with political agendas. He pointed out that some European immigrants weren't considered "white" in 19th-century America, when they were new and unwelcome.

Some of the students smirked. Others just looked confused. How could the idea of race, with its major role in history and politics, be made up?

Many people dismiss this claim as fuzzy-headed political correctness, an example of “wokeness” gone too far. Of course race is real and measurable, most people say. If it wasn’t, all those DNA ancestry companies would be out of business by now. Customers don't pay $200 to hear, "Your DNA ancestry results are 100% socially constructed."

It’s complicated.

Yes, there are genetic differences between people of different races and ethnicities. But our understanding of these differences is socially constructed—influenced by our society’s myths and stereotypes. We tend to put people into categories based on skin tone, appearance, and the language they speak. These categories feel very real to us, but they’re not backed up by science.

I'll give you an example. In the fall of 2007, I moved to Washington, DC, for an internship at a nonprofit group. I had some trouble finding temporary housing. Eventually, I settled on an apartment in Arlington already occupied by three female roommates. For the sake of privacy, I'll call them Ingrid, Elsa, and Marisol. The first two were college exchange students from Sweden. The third was an American student from Texas, and I'd be sharing a room with her. After moving in, I learned Marisol was a Latina woman of Mexican-American descent.

I couldn’t have asked for better living arrangements. My new roommates were kind, easygoing, and fun. My Swedish roommates introduced me to their group of friends, who lived in the same building and were all from Sweden or Finland.

When I show people pictures from that fall, they comment on the sheer amount of blonde hair. They also joke that I fit right in with the Scandinavian students. Almost everyone who sees these photos remarks that I look Swedish, too. From appearance alone, it would be easy to assume that the blondes in the pictures (including me) all come from a similar racial and ethnic background. As for my Latina roommate? Well, she’s clearly of different genetic makeup, with her bronze skin and dark hair.

Hold up a minute. I’m sure you’ve been warned that "looks can be deceiving." And that's definitely true when it comes to our understanding of race, ethnicity, and genetics. My Swedish roommates and I might look alike, but that doesn't mean we are alike, genetically or culturally. In fact, we all come from very different ethnic backgrounds.

Ingrid and Elsa both grew up in Sweden and speak Swedish. However, only one is ethnically Swedish. During dinner one night, Elsa explained to me that her mother is Danish and her father is Portuguese. She once remarked, with a laugh, "I guess I'm not actually Swedish at all."

It depends on what we mean by Swedish. Are we talking about language, culture, and nationality, or about genes? Culturally, of course she's Swedish. But genetically, Elsa is half Southern European--an ethnicity we don't associate with blonde hair and blue eyes.

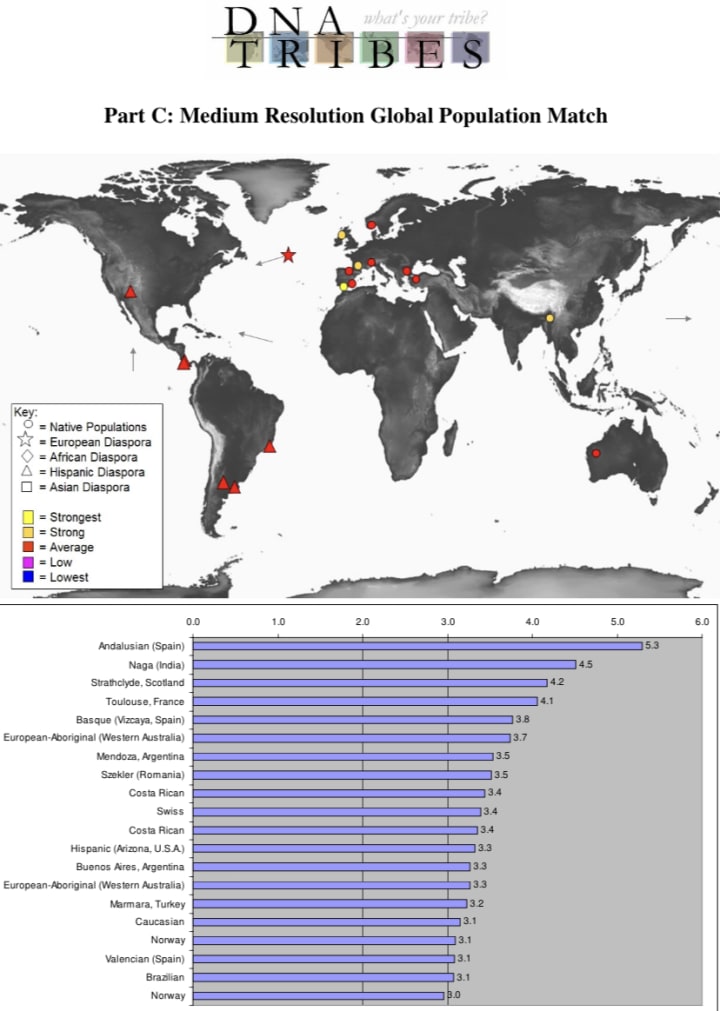

As for me, I've taken more than one ancestry test. I ordered my first test from a company called DNA Tribes way back in 2006. More recently, I've used 23andMe and Ancestry.com. I grew up fairly certain of my ancestral background: my mother is Irish and my father is half Polish and half German.

Or so I thought. My results revealed my assumptions weren't 100% accurate. I was definitely Irish, with some Norwegian DNA, probably from Viking invaders who arrived in Ireland in the Middle Ages. But way back in the genetic line, I also descended from people who were South Asian. DNA Tribes found I was "genetically close" to mixed-race indigenous people in Australia. (I figured this was the result of some Irish forefather of mine getting shipped to a penal colony in the Outback. Thousands of Irish people were sent to Australia as prisoners in the 18th and 19th centuries. The prisoners and the natives, often called “Aborigines,” had a common enemy in their British overlords, and intermixing was not uncommon.)

As for my dad's side, testing confirmed I was a quarter Eastern European, specifically Polish and Russian. But that German DNA was lacking: depending on the company, I was apparently between 0% and 3% German. DNA Tribes--which tests for "deep ancestral roots"--found I was very Spanish, with some Middle Eastern DNA, both from the Andalusia region of Southern Spain, which was once ruled by Muslim conquerors. I had ancestral roots in Basque country and Valencia too.

DNA scientists measure "genetic distance" between individuals and populations to determine their relationship to each other. Some of my closest modern relatives, it turns out, are the people of the "Hispanic Diaspora." My DNA sample was similar to samples submitted by Costa Ricans and Argentineans, as well as—surprise!--self-described Hispanics in Arizona, USA. No matter how different we looked, I was more "racially" similar to my Latina roommate than either of the Swedes.

And what about our friends from Finland, a country that borders Sweden to the east? I always assumed Finnish people were Scandinavian. Finland is often lumped in as the fourth Scandinavian nation, alongside Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. The region is sometimes called "Fennoscandia." When I think of Finland, I think of reindeer, snow, and blondes. Lots of blondes. In fact, all the Finnish people I met in Washington DC had blonde hair and blue eyes.

But Finnish people are a great example of how we erroneously label people because of their skin tone and appearance. Many Finns look Scandinavian. And because of their geographic closeness, there's been a lot of mixing between Swedes and Finns. But historically, these two ethnic groups are not related. The people of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden speak Germanic languages, and their ancient ancestors likely migrated north from present-day Germany. Most Scandinavians belong to Y-DNA Haplogroups R1b or I1. Haplogroups I and R, and their subgroups, are mainly comprised of light-skinned Northwest Europeans who speak Indo-European languages. (Haplogroups are large groups of people who all share a common ancestor. Think of them as big, extended families who all share a Stone Age grandfather.)

Most Finnish people, however, belong to Haplogroup N, which originated in East Asia. Today, most members of Haplogroup N live near the Arctic Circle, in a swath of land that stretches from Finland, across Siberia, and into Korea. The indigenous people of Siberia, as well as Finland’s native reindeer herders, mostly belong to Haplogroup N.

Unlike Scandinavians, Finnish people do not speak a Germanic language. Their language is not even Indo-European. Finnish derives from the Uralic language family, like the languages spoken by native Siberian groups, like the Saami. (Hungarians also speak a Uralic language, which has more in common with the language of Native Greenlanders than with the Slavic languages spoken in neighboring countries, like Poland. Like the Finns, Hungarians are genetically distinct from their neighbors. But for cultural reasons, they’re assigned to the generic category “Eastern European.”)

“[Finns] carry additional ancestry seen as increased allele sharing with modern East Asian populations,” a 2018 article in the journal Nature Communications explained. “The origin and timing of this East Asian-related contribution is unknown… [But] modern Finns are known to possess a distinct genetic structure among today’s European populations.”

It took independent research for me to about Finland—based on my cursory knowledge of European history and geography, I would not have known. Finns are not a Scandinavian people or even a European people. They're a Siberian people, with their own unique history, language and DNA. Of all the ethnic groups that belong to Haplogroup N, Finns are the only ones who are considered "white." Technically, they could be considered Asian. But light-haired, light-skinned people who herd reindeer simply don’t fit our social concept of “Asian.”

This is what it means to say that race is “socially constructed.” It does not mean that there are no DNA differences among groups. It means that the science does not support our superficial assumptions.

In reality, human beings—their various cultures, languages, histories, and genetics—are far more interesting than the bland labels we give them, like “black,” “brown,” and “white.” To say that race is a social construct does not mean we’re all exactly the same. It means the opposite: vague and unscientific categories keep us from seeing the countless little things that make individuals, and cultures, unique.

About the Creator

Ashley Herzog

If you like my work, feel free to tip your writer.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.